Law society of Ontario’s authority: public powers misunderstood

The Law Society of Ontario uses its Governance Practices and Policies to declare that its ‘authority to regulate is a delegated authority from the government of Ontario through the [Law Society] Act’ (s. 5). The Law Society Act does not, however, back this proclamation with convincing proof. The Society’s only connection to government is through the Attorney General for Ontario, ex officio bencher (s. 12[1]). I contend that the Society’s interpretation of its home statute and its position in relation to government are at odds with the principle of an independent legal profession.

The problem with the law society’s interpretation is not apparent at a time when the welfare state folds the executive into the adjudication of disputes. The Supreme Court in Trinity Western’s latest kick at the can viewed law societies as arms of government. The profession should, however, be concerned with this misapprehension. The Law Society of Ontario – the first law society in Canada – was founded as a private college serving the bench. Our modern view shifts this onus from advocates’ traditional role as servants of a court. We instead see the society identifying with executive power.

This issue founds the question I wish to address: whom does the law society serve?

A bland response is: ‘its members’. Indeed, the Law Society is a professional college that bears the hallmarks of an eleemosynary corporation. It is a foundation endowed to preserve its members’ interests. It can award university (collegiate) degrees. Its funds are (notionally) diverted to its members. The Society is, in other words, a charity designed to house legal professionals as a self-regulating and self-training college, thus maintaining an independent profession.

I will briefly detail the history of visitors at the law society and show how the office was suppressed. I will then discuss the possible current visitor, the Attorney General of Ontario. The conclusion to this comment questions the independence of a bar that thinks of itself as an arm of executive government.

Visitors at the Law Society

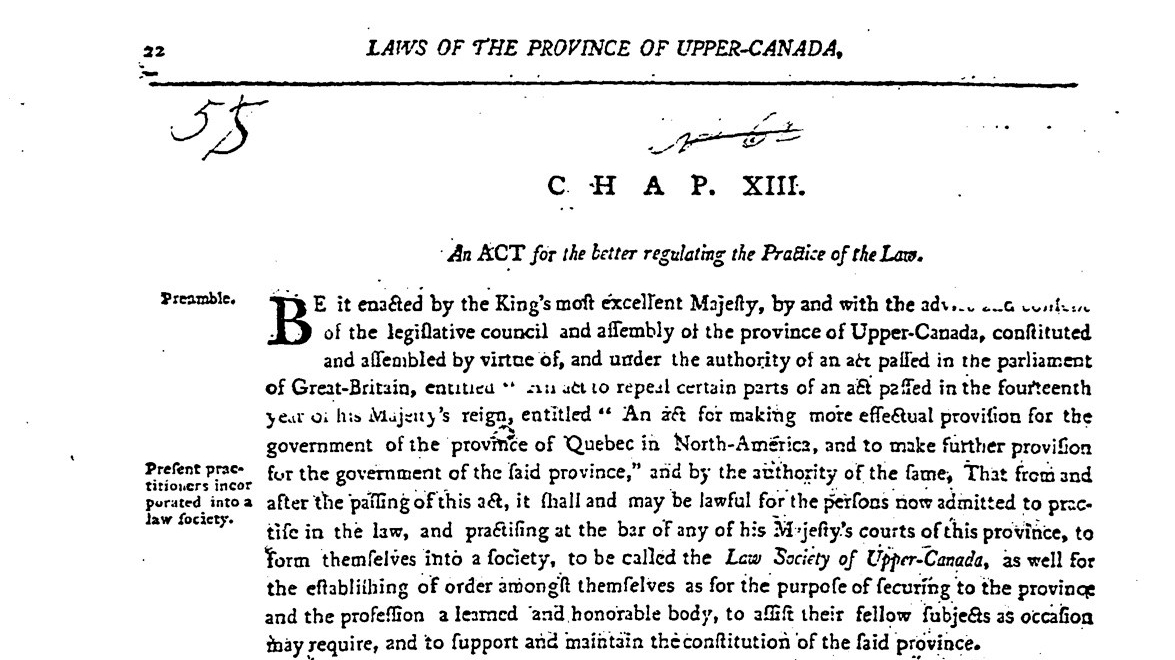

A more lawerly response to my question notices the change wrought by amendments to the Law Society Act in the 1970s. Since 1797, the year of the Law Society’s creation, its legislative charter has mentioned that the judges of superior courts are visitors of the law society. I have elsewhere defined a visitor with citations: visitors have full power to review decisions and statutes of the corporations over which they lord. They can overrule executive and quasi-judicial decisions. They can disallow by-laws. They can even replace by-laws with creations of their own. This little-noticed provision endured as evidence of the British trend across the world: judges supervised lawyers pleading at the bar.

By the 1970s, however, the trend was ready to be forgotten. The Law Society Act was amended. Section 3 of the 1960 Act read: ‘the judges of the Supreme Court are visitors of the Society’. This text was replaced by the requirement for an annual meeting of the members; section 13 was also added:

(1) The Minister of Justice and Attorney General for Ontario shall serve as the guardian of the public interest in all matters within the scope of this Act or having to do with the legal profession in any way, and for this purpose he may at any time require the production of any document, paper, record or thing pertaining to the affairs of the Society.

This innocuous addition transferred a right of inspection from the judges to the Attorney General. The Supreme Court later declared, when reviewing the Saskatchewan Legal Profession Act‘s mention of judges as visitors, that

The unique position of a Judge is reflected by s. 7 of the Legal Profession Act [RSS 1987, c L-10] which designated Judges as visitors of the Society. The title is a hollow and anachronistic one: there is no role or function assigned to a visitor. Nor does a visitor hold an office, or derive any rights from or owe any responsibilities to the Law Society. Whatever it may be, a visitor is not a barrister or solicitor.

Maurice v Priel, [1989] 1 SCR 1023

The Supreme Court of Canada forgot the law. Visitors carry symbolic and substantial weight. They show who is responsible for ultimate oversight of a charitable corporation. That responsibility, though little-exercised, creates rights of appeal from decisions and review of by-laws and regulations.

These powers are sweeping and can be used to correct or undermine the law society’s behaviour, thus affecting the independence of the legal profession a society supervises. While judicial review might lie against a visitor’s decision, that first attack against the society’s decision may prove decisive if the visitor acts within its purview.

Returning to Maurice v Priel for a moment, the Supreme Court’s decision is indicative of the lack of judicial and lawyerly care that sometimes pervades the profession. History shows that law society visitors policed conduct at the bar. Judges were, of course, the logical choice of visitor because they could police individual conduct through contempt and the society’s conduct through visitation.

Current Visitor

Removing explicit mention of judges as visitors means that the legislature returned the right of visitation to the common law from whence it originated. Visitors are appointed by common law, not by statute. A statute that appoints a visitor simply clarifies the law; the law society’s visitor thus still exists in common law, but it takes some digging to find.

Two possibilities exist: the judges may remain visitors, or the Attorney General might have taken up the visitor’s power. This latter option seems more likely because the Attorney General is the ‘guardian of the public interest in all matters within the scope of this Act or having to do with the legal profession in any way’. These words are broad enough to deprive the judges of their reforming power over the law society. The Attorney General instead safeguards the public as the Crown’s first barrister.

If the Attorney General acquires reforming power over the Law Society, that power may be used to undermine the independence of the legal profession. Granted, it does seem unlikely that an Attorney General would so blatantly interfere in the Law Society’s business. The visitor’s powers are also symbolic. They allow lawyers critical of the Law Society and judges on administrative review to link the Society with the executive branch (as has demonstrated in Trinity Western‘s latest kick at the can), thus paving the way for judicial review under Charter norms.

Implications

The implications of this legislative change, if it is successfully argued or even if it acquires persuasive weight, is that the Law Society’s focus has indeed shifted from serving the courts to being regulated by government. This shift is a potential nail in the coffin for an independent legal profession because the regulating body is under the state’s thumb, while individual lawyers still serve the courts. This tension has not, to my knowledge, been discussed. It is, however, an issue that might come to symbolize the profession’s true independence.