Subtle discrimination: Canada’s Civil Aviation Medicine

Check out a.p.strom’s aviation law practise

This post has been updated after correspondence with Transport Canada regarding its aviation medicine certification regime. 21/06/21.

Transport Canada’s Civil Aviation Medicine (CAM) program has continued a discriminatory policy against subjects who present with mental health conditions that would not pose a danger to aviation safety. CAM has done so by misinterpreting and misapplying its enabling legislation. These faults amount to a breach of subjects’ right to equality; they also show that Transport Canada has not minimally impaired subjects’ rights or balanced the purported benefits of its discriminatory policy with the ill effects that subjects with mental health conditions suffer.

This note reviews the CAM program’s legislated standards and policy documents and considers them against the Australian example while applying Canadian human rights norms to show how the discrimination occurs.

Scitote

Aviation safety is, to be abundantly clear, a very legitimate purpose. That legitimacy, however, does not give doctors the ability to impose discriminatory and restrictive standards without an evidence-based rationale that substantially complies with aviation law and with Canadian human rights obligations.

Introduction

The current regime at Canadian Aviation Medicine has, as I have previously indicated, impinged upon subjects’ human rights when they disclose a history of mental health concerns during the medical certification process. After further reflexion, the problem appears to run deeper than previously indicated.

The short version is that Canadian Aviation Medicine aims to certify pilots as safe to fly. Their regulatory documents all indicate that any condition that renders a pilot unable to safely exercise the privileges of her or his license will be denied medical clearance. Canadian Aviation Medical Examiners (‘CAME’) and Regional Aviation Medical Officers (‘RAMO’) are bound to apply Transport Canada policy; that policy currently openly discriminates against mental health concerns by assuming that all mental health conditions render a person unfit to fly based on the prevailing standards.

As stated earlier, the Canadian Aviation Regulations Part IV, Standard 424.17 (4) specifies the physical and mental standards for medical categories. The standard related to mental issues is stated in 1.3 (a), 2.3(a), 3.3(a), 4.3(b):

“The applicant shall have no established medical history or clinical diagnosis which, according to accredited medical conclusion, would render the applicant unable to exercise safely the privileges of the permit, licence or rating applied for or held, as follows: (a) psychosis or established neurosis.”

At first glance this would render anyone with any history of depression, anxiety or other neurosis unfit to be licensed to fly. However, Transport Canada Civil Aviation Medicine has developed an approach to this issue that considers individual circumstances more intently.

Additionally, the use of medications for treatment of these disorders raises regulatory questions as stated in 1.1(d), 2.1(d), 3.1(d), 4.1(d):

“The applicant shall be free from (d) any effect or side effect of any prescribed or non-prescribed therapeutic medication taken, such as would entail a degree of functional incapacity which accredited medical conclusion indicates would interfere with the safe operation of an aircraft during the period of validity of the licence.”

Again, recognizing that the use of medications to treat mental issues is generally a positive step, but does complicate the considerations for medical certification TC CAM has established an approach that individualizes the decision making process.

Handbook for Civil Aviation Medical Examiners – TP 13312, emphasis added.

The discriminatory assumption is subtle, but present: the medical standard requires all medical evaluations to focus on whether the individual can safely operate an aircraft and exercise all of the privileges (and responsibilities) imposed on holders of aviation licenses. This requirement is immediately interpreted by Civil Aviation Medicine as ‘render[ing] anyone with any history of depression, anxiety or other neurosis unfit’. CAM is quick to downplay this statement by advertising its new policy, but its handbook elsewhere indicates that particular ‘psychiatric diseases’ presumptively render a person unfit. The subtle bias signaled by that ‘first glance’ remains, and CAM’s response to a presumptive determination is to immediately begin considering whether the person assumed to be unfit qualifies for an exemption pursuant to sub-section 404.05(1) of the Canadian Aviation Regulations:

(1) The Minister may, in accordance with the personnel licensing standards, issue a medical certificate to an applicant who does not meet the requirements referred to in subsection 404.04(1) where it is in the public interest and is not likely to affect aviation safety.

This exemption relies on a proper determination that an applicant is unable to safely pilot an aircraft or serve as an air traffic controller. Civil aviation medicine’s approach improperly determines this point because it operates on the assumption that all mental health conditions render a person unfit without any additional investigation.

This note shows how Canada’s Civil Aviation Medicine program is constitutionally deficient. Specific reference will be made to sections 15 and 24 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which allows a court to review Transport Canada’s conduct. These sections read:

15 (1) Every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination and, in particular, without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.

24 (1) Anyone whose rights or freedoms, as guaranteed by this Charter, have been infringed or denied may apply to a court of competent jurisdiction to obtain such remedy as the court considers appropriate and just in the circumstances.

Constitution Act, 1982, enacted as Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982, 1982, c. 11 (U.K.)

These provisions come into play as a result of the government’s actions; its legislation (which would be controlled by section 52 of the Charter) is free from bias. This note concludes by calling for a new approach to aviation medical certification that treats subjects with the dignity that section 15 is meant to protect while ensuring aviation safety for all.

Canadian aviation medicine, discrimination, and its effects

Canadian aviation medicine operates under the Aeronautics Act, which is federal legislation that incorporates standards from the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) into Canadian law. Its program is discriminatory not because the law makes it so; the doctors running the program instead make a host of assumptions about mental health that undermines the letter of the law (which may be a crime). The systematic effect of this discrimination perpetrates a violence on subjects that Hannah Arendt describes with brutal prescience:

In a fully developed bureaucracy there is nobody left with whom one can argue, to whom one can present grievances, on whom the pressures of power can be exerted. Bureaucracy is the form of government in which everybody is deprived of political freedom, of the power to act; for the rule by Nobody is not no-rule, and where all are equally powerless we have a tyranny without a tyrant.

On Violence (London: Allen Lane, 1970), p. 81

That initial assumption made within Transport Canada’s bureaucracy creates a hurdle over which subjects have significant problems jumping. The discrimination visited upon these subjects is thus twofold: it creates an immediate denial of the privilege to which they may be legally entitled; it also imposes a much more difficult set of bureaucratic processes to disprove the immediate denial.

This discrimination is typically justified with reference to aviation safety. This justification fails in the measure that its proponents cannot identify specific concerns that would preclude those with any mental health condition from flying. Chronic depression, for example, is treatable and, in some cases, results in no impairment that could affect aviation safety. So, too, is high anxiety. Ignorance is an unfortunate justification. It underscores the need for subjects to navigate the Transport Canada bureaucracy to receive equal treatment.

A common, more informed refrain used to justify Canadian aviation medicine’s biases is that ICAO imposes these standards. The Chicago Convention creates a worldwide set of standards for aviation, which includes medical standards for pilot and air traffic controller (ATC) certification. This shibboleth is quickly disproven by looking to the international context in which Canada’s medical standards exist.

Effect of discrimination

Prior to considering these standards, the effects of Canada’s discriminatory system ought to be fleshed out.

The initial assumption

A medical examination system that begins with an instruction to discriminate is, at first glance, a deeply biased system. The onus (as I have elsewhere shown) rests on individual applicants not only to convince doctors to shake their biases, but also to convince the Government of Canada to change its policy. This is a heavy charge for which most individuals are ill-equipped and under-resourced.

Bias against mental health conditions creates a violation of the Canadian Charter because section 15 requires Transport Canada to apply the law equally to those people who disclose mental health disabilities. The Supreme Court thus said that: ‘The essence of stereotyping … lies in making distinctions against an individual on the basis of personal characteristics attributed to that person not on the basis of his or her true situation, but on the basis of association with a group’ (Winko, para. 87). Canadian Civil Aviation Medicine includes this stereotype in its Handbook for Civil Aviation Medical Examiners. All mental health conditions are presumed to be disqualifying without reference to individual cases.

Transport Canada only takes a case-by-case approach to grant exemptions from the strict medical standards. The burden and cost of obtaining these exemptions falls on individual applicants, pilots, or air traffic controllers.

The Canadian Aviation Regulations, however, which incorporate Standard 424 relating to medical certification, require an individualized process that specifically exempts stereotyping:

The applicant shall have no established medical history or clinical diagnosis which, according to accredited medical conclusion, would render the applicant unable to exercise safely the privileges of the permit, licence or rating applied for or held, as follows:

(a) psychosis or established neurosis;

Physical and Mental Requirement, amended 2007/12/30, emphasis added.

(b) alcohol or chemical dependence or abuse;

(c) a personality or behaviour disorder that has resulted in the commission of an overt act;

(d) other significant mental abnormality.

The required examination must assess whether any of the listed conditions would, in the applicant’s individual circumstances, create a safety hazard.

Standard 424 also indicates that a CAME must grant the highest medical certification possible based on the evidence before them: ‘An applicant shall be granted the highest assessment possible on the basis of the finding recorded during the medical examination.’

Based on these provisions, that Standard is not only constitutionally acceptable. It is an exemplar of the individualized process required by Canadian constitutional law.

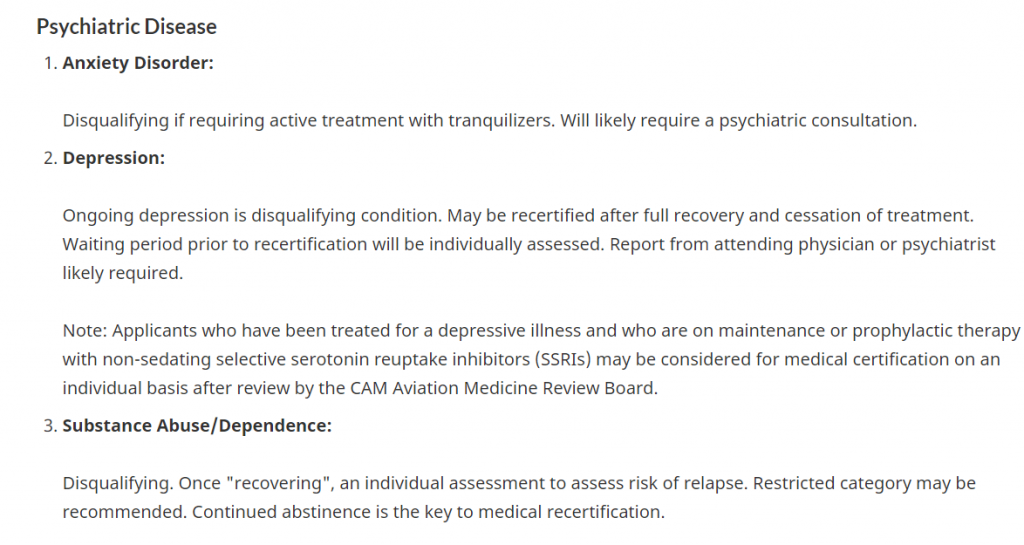

The implementation of this policy, however, leaves much to be desired. The Handbook for Civil Aviation Medical Examiners contains these standards:

The presumption could not be clearer: all anxiety- or depression-related conditions are disqualifying. Pilots are not fit to fly if these conditions are present. The individualized consideration given to applicants appears to fall under section 404.05 of the CARs, which is invoked only when a person is found to be unfit. This added burden creates a disadvantage for applicants with mental health conditions. Transport Canada resists this interpretation, but the use of the words ‘may be considered for medical certification’ after a paragraph that declares depression a disqualifying condition indicates that the disqualification has occurred.

These instructions violate Standard 424 because they do not engage in the required assessment for fitness to fly before implementing the Minister of Transport’s ability to license with conditions.

Pilots and ATC presenting with mental health conditions thus do not benefit from an even application of Standard 424. This discriminatory treatment disadvantages pilots with minor mental health conditions, like dysthymia or some anxiety disorders. These conditions may persist throughout a person’s life and not interfere with her or his aviation duties. They may also be treated with maintenance therapies.

These options are only acknowledged as grounds for exempting a person from medical standards, which means that a professional pilot or ATC may face an indefinite license suspension if she or he discloses a mental health condition. An indefinite suspension is, for most pilots, detrimental to their careers, yet Civil Aviation Medicine does not seem responsive to these grave risks.

Private pilots investing time and money in their hobby are, of course, less affected by these strictures. Their interest is typically more personal. A discriminatory decision from Civil Aviation Medicine will only affect property interests in aircraft or the like.

Either way, though, discrimination hits hard. Research shows that the stigma of perceived discrimination can negatively impact a person’s mental health. An applicant’s pre-existing condition may thus be worsened by Civil Aviation Medicine’s behaviour, which result stands at odds with CAM’s mission and doctors’ ethics.

The violence of bureaucracy

Discrimination is bad enough. Systematic discrimination, for most, is insurmountable due to the sheer size of government bureaucracy. Once this part of the story gets added to the mix, the violence visited upon individuals who disclose that they have a mental health condition becomes acute. The government stands as a representation for wider social stigma, which can be perceived as reflecting Canadian society and/or as reflecting the Canadian aviation community. Either way, stigma that is reinforced by government magnifies the deleterious effects of discrimination on applicants’ mental health.

The wider issue, in bureaucratic terms, is that pre-existing institutional bias that must be reversed by individual applicants creates an institutional culture that prides itself on maintaining bias. Doctors are far from immune to this impulse, specifically as it concerns mental health.

Canadian Civil Aviation Medicine is demonstrative of these ills. The authority accompanies its discriminatory language with discriminatory requirements. CAM automatically imposes a reporting requirement on individuals with mental health conditions. If a person is licensed, they are required to submit medical information about their conditions. Private pilots must submit a report every three months. Professional pilots and air traffic controllers must submit every six. This requirement infantilizes licensees with mental health conditions by assuming that all mental health conditions render a person incapable of judging when she or he is fit to fly. It also duplicates reporting requirements, because treating physicians are required to report any ‘medical or optometric condition that is likely to constitute a hazard to aviation safety’ (Aeronautics Act, s. 6.5). If a licensee decides to stop treatment, for example, a physician would have to report that decision to Transport Canada.

Courts have already recognized that Transport Canada discriminates against individuals presenting with mental health conditions. In Canada v Bethune, the government sought judicial review of a Transportation Appeal Tribunal decision that ordered Transport Canada to reconsider a decision to deny Mr. Bethune medical certification. Mr. Bethune applied for a Category 2 medical certification to become an air traffic controller after passing NAV Canada’s rigorous tests. He had the job, and was forthright in disclosing persistent sadness to the CAME. After several months of waiting, he was forced to decline NAV Canada’s offer because Transport Canada had not yet decided on his medical certification. When it finally ruled against him, he appealed on the grounds that Transport Canada had applied the incorrect policy document: a newer policy was in force. The Tribunal ruled in his favour and held that: ‘The criterion at issue was whether Mr. Bethune had a “significant mental abnormality” that would render him unable to safely exercise the licence at issue – an air traffic controller licence’ (para. 9). The government, worried about precedent, sought judicial review in Federal Court. Justice Phelan agreed with the Tribunal and admonished government counsel in these terms:

It was suggested in argument that no new information would change the Minister’s decision. I take this as a piece of enthusiastic argument and not as a statement of Ministerial policy. If it were policy, there could be grave consequences to a biased and bad faith reconsideration.

Para. 17.

Bethune was decided in 2016; Standard 424 was never at issue in that case. Its application was at issue. The Transportation Appeal Tribunal and the Federal Court each held the government to an individualized process and evidence-based standard that complied with the words in Standard 424. That Standard, to be clear, has not been amended since 2007.

Mr. Bethune’s case unfortunately did not end in cheers. Transport Canada obeyed the letter of the court’s order. It reconsidered the decision. After a year spent waiting, Mr. Bethune was informed that he still did not meet the required medical criteria. Mr. Bethune, frustrated by this dilatory process–one that would wear anyone down–has since happily settled into a fresh line of work.

Ministerial policy has not much changed since Justice Phelan’s admonishment, which brings those ‘grave consequences’ into view. The above-quoted Handbook for Civil Aviation Medical Examiners has not been modified since 2010, when the current discriminatory policy was added as an amelioration to the above-pictured absolute prohibition. Transport Canada’s treatment of Mr. Bethune, moreover, suggests that the Justice Department’s lawyer uttered a premonition in court. Though the judge rightly admonished the Crown, judicial power cannot reform the institutional resistance that ultimately ruined Mr. Bethune’s hopes of becoming an air traffic controller.

Indeed, Transport Canada should be lauded for even considering the prospect that people with mental health conditions take to the skies. Thirty years ago, this was an unthinkable proposition, largely due to ignorance. Now, however, Transport Canada has much more scholarly research about mental health at its disposal. It can craft targeted policies that respond to Canada’s human rights commitments and its concern with aviation safety.

The apathy with which Civil Aviation Medicine has treated this issue runs counter to an evidence-based approach. Justice Phelan commanded such an approach in a specific case, but his writ unfortunately did not extend further.

The resulting lack of close judicial scrutiny means that medical opinion, with its biases, has been allowed to run unchecked through Canadian Civil Aviation Medicine. To be clear, the present cohort of Regional Aviation Medical Officers listed in CAM’s directory are all family physicians whose professional certifications disclose no training or expertise in mental health. This lack of intermediate-level experience may allow biases to run unchecked, for expertise called in at such a remove from individual applicants is at the mercy of pre-established first- and second-line medical opinion.

These opinions in the current regulatory environment identify applicants based on stigma, not individualized analyses. No one person is to blame, but Transport Canada is responsible for a bureaucracy that defines people by a cross-section of traits. These traits then become a person’s institutional identity at Transport Canada. Doctors wind up defining applicants without regard for their dignity or actual aptitudes.

A note about aviation safety

This commentary has so far focused heavily on Transport Canada’s faults. A disbelieving reader might grasp for an easy argument: people with unstable mental health are inherently unpredictable, and medication does not cure such ills. This argument is dated and borne of ignorance regarding the state of research in mental health.

The proper balance between safety and the right to be treated equally for those who have a mental health condition already exists in the Canadian Aviation Regulations. Any health condition must be shown to impair the safe exercise of the privileges of a person’s license. This burden falls upon the doctors employed by Transport Canada.

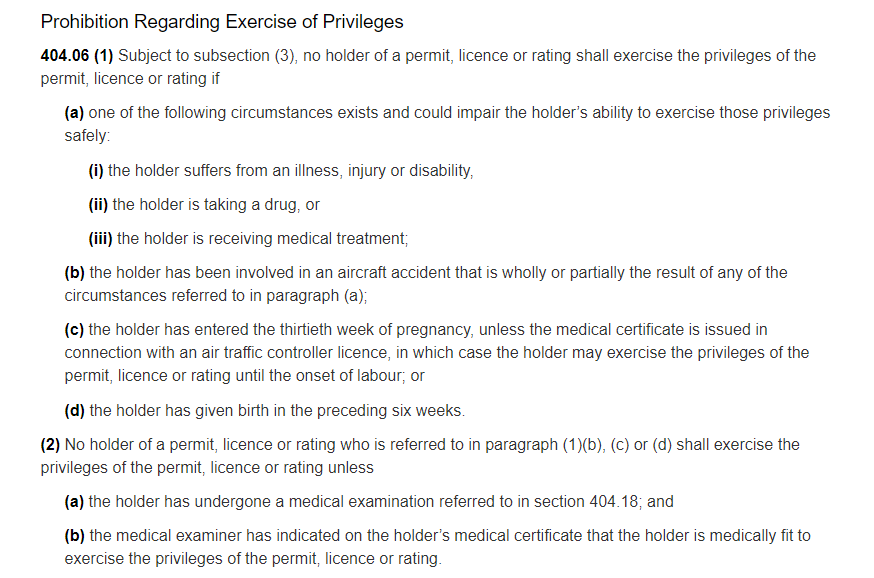

What’s more, once a person is licensed, they are obliged to self-assess prior to each exercise of the privileges associated with her or his license. Section 404.06 of the Canadian Aviation Regulations is crystal clear:

These provisions show that the legislator considered health conditions that could arise during the course of a person’s license. Instead of placing the responsibility upon the Minister of Transport to verify that every pilot is always compliant (an impossible task), the legislator instead made pilots responsible for their conduct.

Civil Aviation Medicine does not address this part of the Civil Aviation Regulations in its policy documents.

The implication, however, of this section is quite broad with respect to mental health. The current policy just discriminates; a more constructive approach in line with aviation safety is to consider mental health in conjunction with the ability to cognize and apply section 404.06. The question then becomes: if a pilot’s depression is such that they cannot safely pilot an aircraft on a particular day, is the pilot able to restrain herself or himself from exercising the privileges of her or his license?

Civil Aviation Medicine would no doubt reply that a pilot in this position could be impaired because some mental illness and associated treatments reduce reaction times. These kinds of problems, however, are legitimate concerns that warrant restrictions on a license or a refusal to license in particular cases, where evidence shows that individuals present safety hazards. The instant problem addresses a catch-all, or blanket approach to mental health that (to its credit) indiscriminately discriminates.

Canadian aviation medicine on the international stage

Other aviation communities have shown far greater leadership when it comes to medical licensing and mental health. Australia’s medical certification regime is a paragon that incorporate open treatment of mental health.

The strengths of Australia’s regime lies in the clarity with which medical standards are promulgated and communicated to doctors and the public. Clarity and a forthright approach to mental health reduce stigma.

Australian civil aviation medicine

Australia’s open approach to mental health conditions relies on regulations that are virtually identical to Canada’s. The difference lies in the country’s approach.

The Civil Aviation Safety Authority’s information page, for example, indicates that each case is unique and there are no textual markers of discrimination. The relevant section of the Designated Aviation Medical Examiners’ clinical practise guidelines indicates that ‘well managed depression is compatible with certification’. The guidelines take a neutral tone; they inform medical specialists about the procedures to be applied in cases that disclose mental health conditions. They also establish patient expectations regarding their condition and the steps needed for certification.

The absence of any mention of mental illness as a disabling condition, although implied, contrasts with Canada’s Handbook for civil aviation medical examiners, which expressly states that mental health conditions are disqualifying. Only after this statement operates on each applicant does Civil Aviation Medicine turn to creating exceptions based on an individual’s condition.

The Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) goes so far as to provide the public and DAME with case scenarios for further clarity.

One such scenario coupled with CASA’s information page is suggestive of Australia’s positive approach. The subject of this scenario is a mid-life initial applicant for a medical certification. The certification is required to obtain a private pilot’s license. The subject discloses a history of depression that has responded well to medication. The subject is alert to his condition and can understand when he is unable to fly. The DAME reviewed the subject’s file, concluded that his condition was not serious enough to warrant rejecting his application. CASA (in this example) issued a certification with the proviso that the subject submit an annual report from his doctor regarding his depression. He was also restricted from flying if his condition or treatment changed pending a DAME review.

This scenario gives applicants and DAMEs a case-based framework with which to understand CASA’s evaluation protocol.

Australia’s Civil Aviation Safety Regulations are, moreover, quite a bit clearer than Canada’s when it comes to medical certification and mental health. Regardless of the class of license, a person is considered fit to fly if they do not have an

established medical history or clinical diagnosis of any of the following conditions, to an extent that is safety?relevant:

(a) psychosis;

(b) significant personality disorder;

(c) significant mental abnormality or neurosis

Tables 67.150, 67. 155, 67.160.

These criteria are a far cry from Canada’s more restrictive criteria in Standard 424, which gestures toward mental health concerns without indicating the severity required to trigger aviation medical certification concerns. Australia’s standard is clear: the mental health condition must rise to a level that significantly impairs a person’s psyche.

This standard coupled with public-facing documents that provide sufficient detail regarding acceptable mental health conditions and outcomes help de-stigmatize mental health in aviation medicine. They have, moreover, not created any significant additional safety concerns.

Rights, minimal impairment, and a proportional rule

Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees equality to all before and under the law. The government may breach this guarantee to ensure social cohesion and public safety (s. 1). Any breaches in this regard must be prescribed by law. Where the law authorizes a breach, that breach must minimally impair subjects’ rights and/or must be proportionate to its policy objectives (R v Oakes). Breaches will often need to be justified with reference to social science evidence (Mounted Police Association of Canada, paras. 143-4).

Canadian aviation medicine’s offending conduct derives from law, but is not itself law. It is a policy of government that dictates Civil Aviation Medicine’s approach to mental health issues. This policy may be defensible as law if it is ‘authorized by statute’ (Greater Vancouver Transportation Authority, para. 65). The above analysis, however, shows that CAM has created a policy that offends its enabling legislation, the Canadian Aviation Regulations. As such, CAM’s policy is not authorized by statute, so its discriminatory conduct cannot be protected by the Charter.

Even if its conduct were protected by the Charter, CAM’s policy does not balance subjects’ right to equality with a very legitimate interest in aviation safety.

The need for balance is prescribed by the venerable Oakes test:

- The objective of the law must be pressing and substantial (aviation safety is pressing and substantial);

- A rational connection must exist between the law and the objective (one does exist in this case);

- The law must be minimally impairing (the law in this case is minimally impairing; CAM’s policy is not);

- The law’s effect on subjects must be proportional to the social benefit derived from the infringement of subjects’ rights (the law in this case is proportional; CAM’s policy is not).

These latter categories create difficulty for Civil Aviation Medicine because any justification of doctors’ conduct requires an admission of disregard for the affected population or a plea of ignorance that arises from a lack of adequate aeromedical specialization in mental health issues.

Minimal impairment is not a difficult standard; it’s the standard of a decent, rational professional. This professional’s knowledge extends to the context in which they work and in which their field is situate. Civil Aviation Medicine, for example, is populated by doctors, whose medical knowledge also allows them to understand the limits of their expertise. These doctors are literate, and have knowledge of the regulatory context in which they work. They are also able to conduct further research on matters related to their duties, whether those be evaluating applicants for medical certification or crafting policy. Keeping to their creed, doctors also advocate for patients to the best of their ability.

This synopsis derives from Canadian jurisprudence regarding minimal impairment. The courts require government to show that it has chosen a policy from a range of reasonable alternatives (Health Services, para. 150). Enhancing the administration of a government program is not minimally impairing, even if such enhancement might benefit a greater population (Health Services, para. 151). The government must instead show that it considered its policy alternatives with regard for the interest of the affected population (Health Services, para. 150; Charkaoui, paras. 76, 86). When government action is being challenged, analogies may be drawn between the duty to accommodate under human rights law and Charter violations to show whether the government did its utmost to protect minority interests (Multani, para. 53). Minimal impairment may, moreover, be made out with reference to other jurisdictions (such as Australia) and to other international treaties to which Canada adheres (Carter, paras. 103-4; JTI Macdonald, para. 10; Whatcott, para. 67).

Civil Aviation Medicine’s current policy fails to show regard for applicants’ interest as a group that is potentially disadvantaged by CAM’s current practise. The practise of assuming that an applicant presenting with a mental health condition is immediately unfit to fly is inductive. It applies a group characteristic (in this case, a stigma) to more efficiently process medical certification applications. I am told that CAM processes over 50,000 of these a year: the current staff have to keep up. The implication of this statement is clear. Applications may be moved along faster than needed to ensure that the system runs smoothly; the courts do not tolerate this excuse. Analogies between the duty to accommodate and CAM’s practices also point to the problem. CAM does not accommodate in the initial phase of an application, where a person’s safety record is not yet in evidence. Accommodation only occurs after Transport Canada has stigmatized the applicant, and this is no accommodation at all if the applicant could have been assessed as medically fit.

Canada’s international obligations overwhelmingly support a more enlightened approach to mental health in aviation. The United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights guarantees a right to equality (article 1) and freedom from discrimination (article 7), subject only to ‘such limitations as are determined by law’ (article 29). The United Nations’ High Commissioner for Human Rights reported in 2017 that: ‘the experience of living with mental health conditions is shaped, to a great extent, by the historical and continuing marginalization of mental health in public policy’ (para. 14). The Commissioner went on to say that:

This stereotyping, prejudice and stigmatization is present in every sphere of life, including social, educational, work and health-care settings, and profoundly affects the regard in which the individual is held, as well as their own self-esteem. The lack of systematic training and awareness-raising for mental health personnel on human rights as they apply to mental health allows stigma to continue in health settings, which compromises care.

…

The full participation of affected communities in the development, implementation and monitoring of policy has a positive impact on health outcomes and on the realization of their human rights. Ensuring their participation supports the development of responses that are relevant to the context and ensures that policies are effective. Participation in lawmaking and policy design in mental health has typically been directed at health professionals, as a result of which the concerns and views of users, persons with mental health conditions and persons with psychosocial disabilities have not been systematically taken into account and harmful practices have been perpetuated and institutionalized in law and policies.

Paras. 16, 43.

ICAO, an organization based in Montreal, is closely affiliated with the United Nations. Its membership requires that a state also possess membership in the United Nations (Chicago Convention, art. 93 bis). UN members are subject to human rights obligations stemming from the UN; ICAO’s membership is subjected to those obligations. Medical standards promulgated under the Chicago Convention must therefore accord with international human rights obligations.

The last phase of the Oakes test balances the effect of a practise on individuals with its positive outcome for the general population (Frank, para. 76; KRJ, paras. 77-8).

The effects of CAM’s practise have been noted above. Their rehearsal here is only to note that the treatment of mental health conditions afforded to prospective and actual pilots and air traffic controllers can have life-altering consequences. Discrimination and perceived discrimination violate a person’s dignity and can impact her or his self-esteem. More critically still, CAM’s treatment may worsen a person’s mental health. Professional pilots and air traffic controllers may lose their livelihoods, which is a stressor that impacts mental health. It only takes a few words to capture these consequences, but for those affected by mental health conditions, the ramifications are much broader. The stigma still associated with mental health is, as noted above, enhanced when it is directed by the impersonal face of government. Individual well-being is seriously undermined.

The social benefit derived from such discrimination is minimal at best. Aviation safety is adequately protected when Civil Aviation Medicine turns its attention to the individual applicant in order to assess her or his actual ability. Treating physicians are, moreover, required to report any potential risks to aviation safety. The mechanisms maintain the balance between aviation safety and individual rights. A blanket prohibition that requires applicants to prove their fitness for an exception to that prohibition only serves to make Civil Aviation Medicine’s case processing more efficient. It does not address the legitimate aviation safety concerns that benefit society.

The effect of CAM’s policy is, then, far more dire than further adjustments to its policy.