Business research is often viewed as a wish-list item. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Business research is akin to performing preventive maintenance on a car while inventing new technology for the vehicle. It can save a business’ bacon and increase its productivity.

There is little talk about business research as an organized activity. Corporate research gets some attention, but business research falls flat. The difference is one of scale. Corporations that fund research departments often have considerable resources at their disposal. Smaller firms have it or they don’t; attend a librarians’ conference if you’d like to hear more. Some companies specialize in market research; other, larger companies, provide global solutions. These divisions are suitable for a bygone era, where divisions of labour were relatively clear and large businesses abounded. The expanding gig economy and an increasing presence of digital disruptors means that less clear divisions exist. This fog of war gives smaller, more dynamic firms the ability to gain ground.

‘Business research’ in this context means more than corporate or market research. It embraces the strategic and tactical dimensions of corporate and market research while also fulfilling the gig economy’s need for client-focused, local research. That is to say, business research embraces an enterprise’s front and back ends to deliver seamless service. It is an essential part of the gig economy and Industry 4.0, for the gig economy’s main means of exchange is through the information super-highway. Business research processes digital and analog information to create or encode most every product that we possess.

This changing landscape affords a fresh understanding of business research suited to gig workers and disruptors. All that’s needed is a glance at a humble librarian’s career at the end of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, where the changes to research and knowledge management revolutionized the librarian’s and the researcher’s roles…only to maintain the cardinal principle that makes business research worthwhile.

My father was a librarian who spent his career organizing and tending to corporate knowledge. He mainly worked in big firms providing corporate and market research. The libraries in which he worked were designed to support profit centers.

I remember spending my childhood in those libraries, and my formative years were traditional libraries’ last kick at the can. I’d go to work with my dad and spend time antagonizing (in retrospect) very kind librarians. My love of books no doubt sprung from these interactions.

As we delve into the twenty-first century, however, physical libraries become less relevant. I saw this firsthand with my pops, whose role began to emphasize finding information over organizing it. These roles, of course, go hand in hand. Information is only found by those who understand it’s organization.

The scale on which electronic, networked, organization is conducted changed the game. The information with which my father dealt in the last year’s of his career was more mercurial than ever. Large data sets and the availability of qualitative sources made it relatively easy to know something without understanding anything. The large firms at which my dad worked were able to move past this barrier to entry. They employed analysts and librarians to interpret massive databases.

Therein lies the problem. The work of interpreting such databases is increasingly being completed by machines that are inherently quantitative mechanisms. Large companies’ economies of scale continue to scale, and librarians like my father find themselves redundant in a new world that sometimes forgets the importance of human research.

The career that my father wound up traced the great lines of this forgetting–and Ray Bradbury would be proud of the results. It’s now difficult to track news in a deluge of information, let alone discrete research tasks. Why not let a computer do the heavy lifting? Librarians are costly investments and the results of their efforts are fallible. Work to the bottom line.

My old man’s career cut through the process of forgetting. He walked out of a master’s degree in library science in 1993 and started work at a public library. He quickly moved to corporate libraries, and the job became increasingly digital. Part of the change was due to the new environment. Another part was the changing means with which we store and access information. These factors play into our ability to forget. They pale, however, on comparison to insistence on maximum efficiency. As the oughts became the teens, by father was subjected to an increasing standard of professional responsiveness. The data existed, therefore he could find the information, and find it quick thanks to technological innovations.

Research, however, is not affected by the amount of available information. A researcher still has to do the work of finding and compiling the right details.

The burden placed on my father and his fellow corporate librarians to get business research done right and faster than ever guaranteed that their work would be undervalued. His eventual redundancy resulted from the expectation of instant gratification that computerized research provides. Partners and associates didn’t feel the need to consult a researcher when they could pull results that seemingly provided a complete description from a Google search, or a corporate dataset.

Hence partners and associates forgetting the importance of business research in the large firm. The pressures in a corporate economy often get the better of business researchers’ end-users. Other things might move quickly, but the fact of the matter is that quality research takes time, and that doesn’t just mean working overtime to produce some result.

Human research captures the nuance of each problem, and such nuance is critical when working with customers or colleagues. It marks the difference between showing that one cares for the others’ interests and an attitude that reduces a person’s interests to a problem that needs solving.

The corollary to this observation is that research is creative. Drawing different strands of networked information together generates new ideas. The methods used build value, because they refine the way in which knowledge is stored and how it can be retrieved. The end result creates and inspires new thoughts. It passes information through the funnel that is a researcher’s mind. Each instance, procedural or substantive, breeds novelty.

The value in this human phenomenon is oftentimes displaced by immediate concerns. The sausage gets made without regard for the consequences.

One of those consequences is the loss of respect for the researcher or the knowledge manager. They are erudite gatekeepers removed from practise, punctilious: abstract. Indeed they can be so many words. They are also diligent workers and able institutional resources. These qualities shine through in the long term. People often only see the bottom line.

The tools that changed my dad’s job also give it new meaning.

Librarians and researchers now contend with a virtually infinite knowledge base. Pinning the issues down is more complex, with greater diversity of opinion, because those opinions are readily accessible in a click. They no longer curate physical collections.

This changed job description nevertheless maintains its roots: librarians and researchers must still dedicate their working lives to understanding others’ needs, translating those needs into research questions, and building answers. Those answers are needed without delay and are subject to information that changes instantly with electronic publication. The job isn’t for everyone, yet employing a researcher is beyond most people’s means.

Hence the appearance of freelance or subscription researchers, whose role is to serve as trusted advisor and knowledge base. This role can help small businesses by enhancing their market intelligence at affordable rates; it can also build strategic insights, thus allowing businesses to change tack on a dime. For lawyers in particular, third-party researchers check biases and question arguments. These functions ultimately make for stronger businesses and better representation.

The short form? Consider building a relationship with a researcher.

Check out a.p.strom’s aviation law practise

This post has been updated after correspondence with Transport Canada regarding its aviation medicine certification regime. 21/06/21.

Transport Canada’s Civil Aviation Medicine (CAM) program has continued a discriminatory policy against subjects who present with mental health conditions that would not pose a danger to aviation safety. CAM has done so by misinterpreting and misapplying its enabling legislation. These faults amount to a breach of subjects’ right to equality; they also show that Transport Canada has not minimally impaired subjects’ rights or balanced the purported benefits of its discriminatory policy with the ill effects that subjects with mental health conditions suffer.

This note reviews the CAM program’s legislated standards and policy documents and considers them against the Australian example while applying Canadian human rights norms to show how the discrimination occurs.

Scitote

Aviation safety is, to be abundantly clear, a very legitimate purpose. That legitimacy, however, does not give doctors the ability to impose discriminatory and restrictive standards without an evidence-based rationale that substantially complies with aviation law and with Canadian human rights obligations.

Introduction

The current regime at Canadian Aviation Medicine has, as I have previously indicated, impinged upon subjects’ human rights when they disclose a history of mental health concerns during the medical certification process. After further reflexion, the problem appears to run deeper than previously indicated.

The short version is that Canadian Aviation Medicine aims to certify pilots as safe to fly. Their regulatory documents all indicate that any condition that renders a pilot unable to safely exercise the privileges of her or his license will be denied medical clearance. Canadian Aviation Medical Examiners (‘CAME’) and Regional Aviation Medical Officers (‘RAMO’) are bound to apply Transport Canada policy; that policy currently openly discriminates against mental health concerns by assuming that all mental health conditions render a person unfit to fly based on the prevailing standards.

As stated earlier, the Canadian Aviation Regulations Part IV, Standard 424.17 (4) specifies the physical and mental standards for medical categories. The standard related to mental issues is stated in 1.3 (a), 2.3(a), 3.3(a), 4.3(b):

“The applicant shall have no established medical history or clinical diagnosis which, according to accredited medical conclusion, would render the applicant unable to exercise safely the privileges of the permit, licence or rating applied for or held, as follows: (a) psychosis or established neurosis.”

At first glance this would render anyone with any history of depression, anxiety or other neurosis unfit to be licensed to fly. However, Transport Canada Civil Aviation Medicine has developed an approach to this issue that considers individual circumstances more intently.

Additionally, the use of medications for treatment of these disorders raises regulatory questions as stated in 1.1(d), 2.1(d), 3.1(d), 4.1(d):

“The applicant shall be free from (d) any effect or side effect of any prescribed or non-prescribed therapeutic medication taken, such as would entail a degree of functional incapacity which accredited medical conclusion indicates would interfere with the safe operation of an aircraft during the period of validity of the licence.”

Again, recognizing that the use of medications to treat mental issues is generally a positive step, but does complicate the considerations for medical certification TC CAM has established an approach that individualizes the decision making process.

Handbook for Civil Aviation Medical Examiners – TP 13312, emphasis added.

The discriminatory assumption is subtle, but present: the medical standard requires all medical evaluations to focus on whether the individual can safely operate an aircraft and exercise all of the privileges (and responsibilities) imposed on holders of aviation licenses. This requirement is immediately interpreted by Civil Aviation Medicine as ‘render[ing] anyone with any history of depression, anxiety or other neurosis unfit’. CAM is quick to downplay this statement by advertising its new policy, but its handbook elsewhere indicates that particular ‘psychiatric diseases’ presumptively render a person unfit. The subtle bias signaled by that ‘first glance’ remains, and CAM’s response to a presumptive determination is to immediately begin considering whether the person assumed to be unfit qualifies for an exemption pursuant to sub-section 404.05(1) of the Canadian Aviation Regulations:

(1) The Minister may, in accordance with the personnel licensing standards, issue a medical certificate to an applicant who does not meet the requirements referred to in subsection 404.04(1) where it is in the public interest and is not likely to affect aviation safety.

This exemption relies on a proper determination that an applicant is unable to safely pilot an aircraft or serve as an air traffic controller. Civil aviation medicine’s approach improperly determines this point because it operates on the assumption that all mental health conditions render a person unfit without any additional investigation.

This note shows how Canada’s Civil Aviation Medicine program is constitutionally deficient. Specific reference will be made to sections 15 and 24 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which allows a court to review Transport Canada’s conduct. These sections read:

15 (1) Every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination and, in particular, without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.

24 (1) Anyone whose rights or freedoms, as guaranteed by this Charter, have been infringed or denied may apply to a court of competent jurisdiction to obtain such remedy as the court considers appropriate and just in the circumstances.

Constitution Act, 1982, enacted as Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982, 1982, c. 11 (U.K.)

These provisions come into play as a result of the government’s actions; its legislation (which would be controlled by section 52 of the Charter) is free from bias. This note concludes by calling for a new approach to aviation medical certification that treats subjects with the dignity that section 15 is meant to protect while ensuring aviation safety for all.

Canadian aviation medicine, discrimination, and its effects

Canadian aviation medicine operates under the Aeronautics Act, which is federal legislation that incorporates standards from the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) into Canadian law. Its program is discriminatory not because the law makes it so; the doctors running the program instead make a host of assumptions about mental health that undermines the letter of the law (which may be a crime). The systematic effect of this discrimination perpetrates a violence on subjects that Hannah Arendt describes with brutal prescience:

In a fully developed bureaucracy there is nobody left with whom one can argue, to whom one can present grievances, on whom the pressures of power can be exerted. Bureaucracy is the form of government in which everybody is deprived of political freedom, of the power to act; for the rule by Nobody is not no-rule, and where all are equally powerless we have a tyranny without a tyrant.

On Violence (London: Allen Lane, 1970), p. 81

That initial assumption made within Transport Canada’s bureaucracy creates a hurdle over which subjects have significant problems jumping. The discrimination visited upon these subjects is thus twofold: it creates an immediate denial of the privilege to which they may be legally entitled; it also imposes a much more difficult set of bureaucratic processes to disprove the immediate denial.

This discrimination is typically justified with reference to aviation safety. This justification fails in the measure that its proponents cannot identify specific concerns that would preclude those with any mental health condition from flying. Chronic depression, for example, is treatable and, in some cases, results in no impairment that could affect aviation safety. So, too, is high anxiety. Ignorance is an unfortunate justification. It underscores the need for subjects to navigate the Transport Canada bureaucracy to receive equal treatment.

A common, more informed refrain used to justify Canadian aviation medicine’s biases is that ICAO imposes these standards. The Chicago Convention creates a worldwide set of standards for aviation, which includes medical standards for pilot and air traffic controller (ATC) certification. This shibboleth is quickly disproven by looking to the international context in which Canada’s medical standards exist.

Effect of discrimination

Prior to considering these standards, the effects of Canada’s discriminatory system ought to be fleshed out.

The initial assumption

A medical examination system that begins with an instruction to discriminate is, at first glance, a deeply biased system. The onus (as I have elsewhere shown) rests on individual applicants not only to convince doctors to shake their biases, but also to convince the Government of Canada to change its policy. This is a heavy charge for which most individuals are ill-equipped and under-resourced.

Bias against mental health conditions creates a violation of the Canadian Charter because section 15 requires Transport Canada to apply the law equally to those people who disclose mental health disabilities. The Supreme Court thus said that: ‘The essence of stereotyping … lies in making distinctions against an individual on the basis of personal characteristics attributed to that person not on the basis of his or her true situation, but on the basis of association with a group’ (Winko, para. 87). Canadian Civil Aviation Medicine includes this stereotype in its Handbook for Civil Aviation Medical Examiners. All mental health conditions are presumed to be disqualifying without reference to individual cases.

Transport Canada only takes a case-by-case approach to grant exemptions from the strict medical standards. The burden and cost of obtaining these exemptions falls on individual applicants, pilots, or air traffic controllers.

The Canadian Aviation Regulations, however, which incorporate Standard 424 relating to medical certification, require an individualized process that specifically exempts stereotyping:

The applicant shall have no established medical history or clinical diagnosis which, according to accredited medical conclusion, would render the applicant unable to exercise safely the privileges of the permit, licence or rating applied for or held, as follows:

(a) psychosis or established neurosis;

Physical and Mental Requirement, amended 2007/12/30, emphasis added.

(b) alcohol or chemical dependence or abuse;

(c) a personality or behaviour disorder that has resulted in the commission of an overt act;

(d) other significant mental abnormality.

The required examination must assess whether any of the listed conditions would, in the applicant’s individual circumstances, create a safety hazard.

Standard 424 also indicates that a CAME must grant the highest medical certification possible based on the evidence before them: ‘An applicant shall be granted the highest assessment possible on the basis of the finding recorded during the medical examination.’

Based on these provisions, that Standard is not only constitutionally acceptable. It is an exemplar of the individualized process required by Canadian constitutional law.

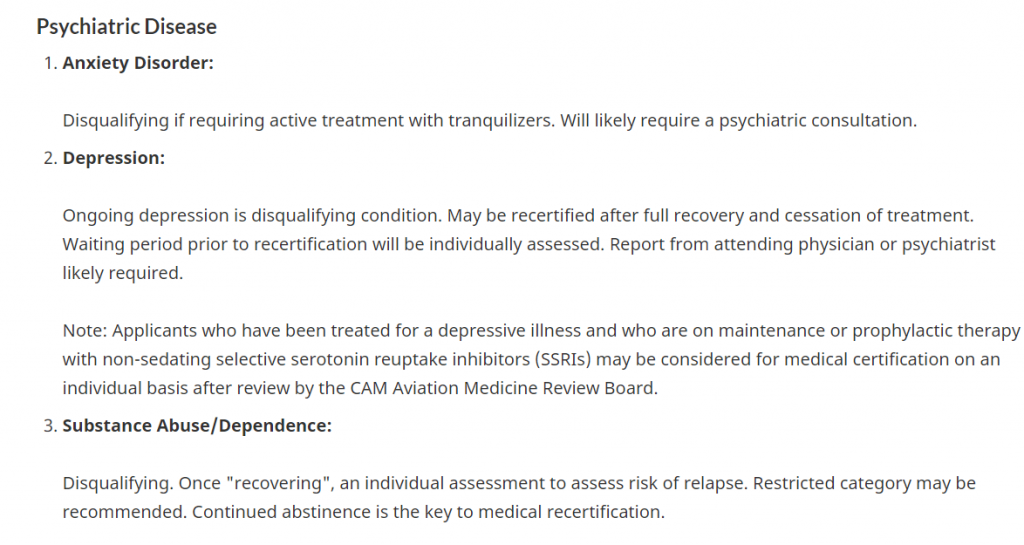

The implementation of this policy, however, leaves much to be desired. The Handbook for Civil Aviation Medical Examiners contains these standards:

The presumption could not be clearer: all anxiety- or depression-related conditions are disqualifying. Pilots are not fit to fly if these conditions are present. The individualized consideration given to applicants appears to fall under section 404.05 of the CARs, which is invoked only when a person is found to be unfit. This added burden creates a disadvantage for applicants with mental health conditions. Transport Canada resists this interpretation, but the use of the words ‘may be considered for medical certification’ after a paragraph that declares depression a disqualifying condition indicates that the disqualification has occurred.

These instructions violate Standard 424 because they do not engage in the required assessment for fitness to fly before implementing the Minister of Transport’s ability to license with conditions.

Pilots and ATC presenting with mental health conditions thus do not benefit from an even application of Standard 424. This discriminatory treatment disadvantages pilots with minor mental health conditions, like dysthymia or some anxiety disorders. These conditions may persist throughout a person’s life and not interfere with her or his aviation duties. They may also be treated with maintenance therapies.

These options are only acknowledged as grounds for exempting a person from medical standards, which means that a professional pilot or ATC may face an indefinite license suspension if she or he discloses a mental health condition. An indefinite suspension is, for most pilots, detrimental to their careers, yet Civil Aviation Medicine does not seem responsive to these grave risks.

Private pilots investing time and money in their hobby are, of course, less affected by these strictures. Their interest is typically more personal. A discriminatory decision from Civil Aviation Medicine will only affect property interests in aircraft or the like.

Either way, though, discrimination hits hard. Research shows that the stigma of perceived discrimination can negatively impact a person’s mental health. An applicant’s pre-existing condition may thus be worsened by Civil Aviation Medicine’s behaviour, which result stands at odds with CAM’s mission and doctors’ ethics.

The violence of bureaucracy

Discrimination is bad enough. Systematic discrimination, for most, is insurmountable due to the sheer size of government bureaucracy. Once this part of the story gets added to the mix, the violence visited upon individuals who disclose that they have a mental health condition becomes acute. The government stands as a representation for wider social stigma, which can be perceived as reflecting Canadian society and/or as reflecting the Canadian aviation community. Either way, stigma that is reinforced by government magnifies the deleterious effects of discrimination on applicants’ mental health.

The wider issue, in bureaucratic terms, is that pre-existing institutional bias that must be reversed by individual applicants creates an institutional culture that prides itself on maintaining bias. Doctors are far from immune to this impulse, specifically as it concerns mental health.

Canadian Civil Aviation Medicine is demonstrative of these ills. The authority accompanies its discriminatory language with discriminatory requirements. CAM automatically imposes a reporting requirement on individuals with mental health conditions. If a person is licensed, they are required to submit medical information about their conditions. Private pilots must submit a report every three months. Professional pilots and air traffic controllers must submit every six. This requirement infantilizes licensees with mental health conditions by assuming that all mental health conditions render a person incapable of judging when she or he is fit to fly. It also duplicates reporting requirements, because treating physicians are required to report any ‘medical or optometric condition that is likely to constitute a hazard to aviation safety’ (Aeronautics Act, s. 6.5). If a licensee decides to stop treatment, for example, a physician would have to report that decision to Transport Canada.

Courts have already recognized that Transport Canada discriminates against individuals presenting with mental health conditions. In Canada v Bethune, the government sought judicial review of a Transportation Appeal Tribunal decision that ordered Transport Canada to reconsider a decision to deny Mr. Bethune medical certification. Mr. Bethune applied for a Category 2 medical certification to become an air traffic controller after passing NAV Canada’s rigorous tests. He had the job, and was forthright in disclosing persistent sadness to the CAME. After several months of waiting, he was forced to decline NAV Canada’s offer because Transport Canada had not yet decided on his medical certification. When it finally ruled against him, he appealed on the grounds that Transport Canada had applied the incorrect policy document: a newer policy was in force. The Tribunal ruled in his favour and held that: ‘The criterion at issue was whether Mr. Bethune had a “significant mental abnormality” that would render him unable to safely exercise the licence at issue – an air traffic controller licence’ (para. 9). The government, worried about precedent, sought judicial review in Federal Court. Justice Phelan agreed with the Tribunal and admonished government counsel in these terms:

It was suggested in argument that no new information would change the Minister’s decision. I take this as a piece of enthusiastic argument and not as a statement of Ministerial policy. If it were policy, there could be grave consequences to a biased and bad faith reconsideration.

Para. 17.

Bethune was decided in 2016; Standard 424 was never at issue in that case. Its application was at issue. The Transportation Appeal Tribunal and the Federal Court each held the government to an individualized process and evidence-based standard that complied with the words in Standard 424. That Standard, to be clear, has not been amended since 2007.

Mr. Bethune’s case unfortunately did not end in cheers. Transport Canada obeyed the letter of the court’s order. It reconsidered the decision. After a year spent waiting, Mr. Bethune was informed that he still did not meet the required medical criteria. Mr. Bethune, frustrated by this dilatory process–one that would wear anyone down–has since happily settled into a fresh line of work.

Ministerial policy has not much changed since Justice Phelan’s admonishment, which brings those ‘grave consequences’ into view. The above-quoted Handbook for Civil Aviation Medical Examiners has not been modified since 2010, when the current discriminatory policy was added as an amelioration to the above-pictured absolute prohibition. Transport Canada’s treatment of Mr. Bethune, moreover, suggests that the Justice Department’s lawyer uttered a premonition in court. Though the judge rightly admonished the Crown, judicial power cannot reform the institutional resistance that ultimately ruined Mr. Bethune’s hopes of becoming an air traffic controller.

Indeed, Transport Canada should be lauded for even considering the prospect that people with mental health conditions take to the skies. Thirty years ago, this was an unthinkable proposition, largely due to ignorance. Now, however, Transport Canada has much more scholarly research about mental health at its disposal. It can craft targeted policies that respond to Canada’s human rights commitments and its concern with aviation safety.

The apathy with which Civil Aviation Medicine has treated this issue runs counter to an evidence-based approach. Justice Phelan commanded such an approach in a specific case, but his writ unfortunately did not extend further.

The resulting lack of close judicial scrutiny means that medical opinion, with its biases, has been allowed to run unchecked through Canadian Civil Aviation Medicine. To be clear, the present cohort of Regional Aviation Medical Officers listed in CAM’s directory are all family physicians whose professional certifications disclose no training or expertise in mental health. This lack of intermediate-level experience may allow biases to run unchecked, for expertise called in at such a remove from individual applicants is at the mercy of pre-established first- and second-line medical opinion.

These opinions in the current regulatory environment identify applicants based on stigma, not individualized analyses. No one person is to blame, but Transport Canada is responsible for a bureaucracy that defines people by a cross-section of traits. These traits then become a person’s institutional identity at Transport Canada. Doctors wind up defining applicants without regard for their dignity or actual aptitudes.

A note about aviation safety

This commentary has so far focused heavily on Transport Canada’s faults. A disbelieving reader might grasp for an easy argument: people with unstable mental health are inherently unpredictable, and medication does not cure such ills. This argument is dated and borne of ignorance regarding the state of research in mental health.

The proper balance between safety and the right to be treated equally for those who have a mental health condition already exists in the Canadian Aviation Regulations. Any health condition must be shown to impair the safe exercise of the privileges of a person’s license. This burden falls upon the doctors employed by Transport Canada.

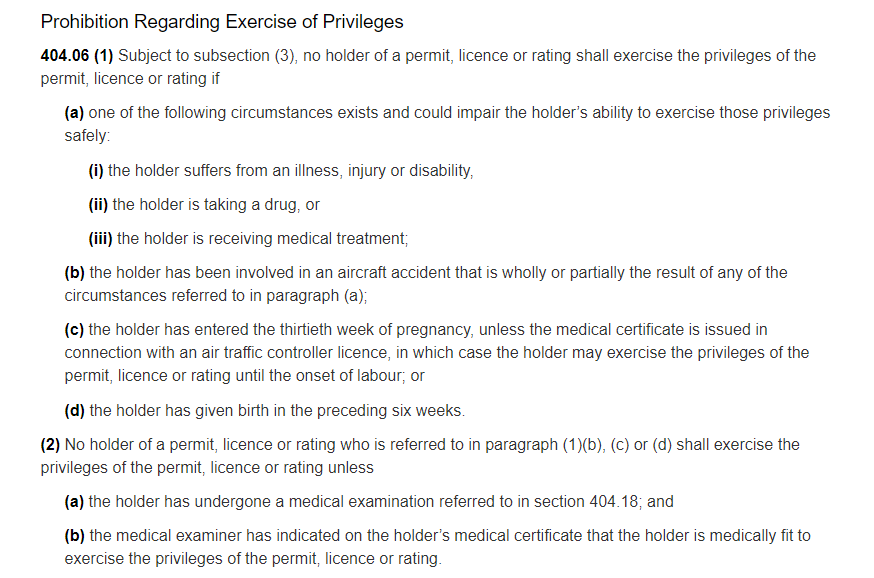

What’s more, once a person is licensed, they are obliged to self-assess prior to each exercise of the privileges associated with her or his license. Section 404.06 of the Canadian Aviation Regulations is crystal clear:

These provisions show that the legislator considered health conditions that could arise during the course of a person’s license. Instead of placing the responsibility upon the Minister of Transport to verify that every pilot is always compliant (an impossible task), the legislator instead made pilots responsible for their conduct.

Civil Aviation Medicine does not address this part of the Civil Aviation Regulations in its policy documents.

The implication, however, of this section is quite broad with respect to mental health. The current policy just discriminates; a more constructive approach in line with aviation safety is to consider mental health in conjunction with the ability to cognize and apply section 404.06. The question then becomes: if a pilot’s depression is such that they cannot safely pilot an aircraft on a particular day, is the pilot able to restrain herself or himself from exercising the privileges of her or his license?

Civil Aviation Medicine would no doubt reply that a pilot in this position could be impaired because some mental illness and associated treatments reduce reaction times. These kinds of problems, however, are legitimate concerns that warrant restrictions on a license or a refusal to license in particular cases, where evidence shows that individuals present safety hazards. The instant problem addresses a catch-all, or blanket approach to mental health that (to its credit) indiscriminately discriminates.

Canadian aviation medicine on the international stage

Other aviation communities have shown far greater leadership when it comes to medical licensing and mental health. Australia’s medical certification regime is a paragon that incorporate open treatment of mental health.

The strengths of Australia’s regime lies in the clarity with which medical standards are promulgated and communicated to doctors and the public. Clarity and a forthright approach to mental health reduce stigma.

Australian civil aviation medicine

Australia’s open approach to mental health conditions relies on regulations that are virtually identical to Canada’s. The difference lies in the country’s approach.

The Civil Aviation Safety Authority’s information page, for example, indicates that each case is unique and there are no textual markers of discrimination. The relevant section of the Designated Aviation Medical Examiners’ clinical practise guidelines indicates that ‘well managed depression is compatible with certification’. The guidelines take a neutral tone; they inform medical specialists about the procedures to be applied in cases that disclose mental health conditions. They also establish patient expectations regarding their condition and the steps needed for certification.

The absence of any mention of mental illness as a disabling condition, although implied, contrasts with Canada’s Handbook for civil aviation medical examiners, which expressly states that mental health conditions are disqualifying. Only after this statement operates on each applicant does Civil Aviation Medicine turn to creating exceptions based on an individual’s condition.

The Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) goes so far as to provide the public and DAME with case scenarios for further clarity.

One such scenario coupled with CASA’s information page is suggestive of Australia’s positive approach. The subject of this scenario is a mid-life initial applicant for a medical certification. The certification is required to obtain a private pilot’s license. The subject discloses a history of depression that has responded well to medication. The subject is alert to his condition and can understand when he is unable to fly. The DAME reviewed the subject’s file, concluded that his condition was not serious enough to warrant rejecting his application. CASA (in this example) issued a certification with the proviso that the subject submit an annual report from his doctor regarding his depression. He was also restricted from flying if his condition or treatment changed pending a DAME review.

This scenario gives applicants and DAMEs a case-based framework with which to understand CASA’s evaluation protocol.

Australia’s Civil Aviation Safety Regulations are, moreover, quite a bit clearer than Canada’s when it comes to medical certification and mental health. Regardless of the class of license, a person is considered fit to fly if they do not have an

established medical history or clinical diagnosis of any of the following conditions, to an extent that is safety?relevant:

(a) psychosis;

(b) significant personality disorder;

(c) significant mental abnormality or neurosis

Tables 67.150, 67. 155, 67.160.

These criteria are a far cry from Canada’s more restrictive criteria in Standard 424, which gestures toward mental health concerns without indicating the severity required to trigger aviation medical certification concerns. Australia’s standard is clear: the mental health condition must rise to a level that significantly impairs a person’s psyche.

This standard coupled with public-facing documents that provide sufficient detail regarding acceptable mental health conditions and outcomes help de-stigmatize mental health in aviation medicine. They have, moreover, not created any significant additional safety concerns.

Rights, minimal impairment, and a proportional rule

Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees equality to all before and under the law. The government may breach this guarantee to ensure social cohesion and public safety (s. 1). Any breaches in this regard must be prescribed by law. Where the law authorizes a breach, that breach must minimally impair subjects’ rights and/or must be proportionate to its policy objectives (R v Oakes). Breaches will often need to be justified with reference to social science evidence (Mounted Police Association of Canada, paras. 143-4).

Canadian aviation medicine’s offending conduct derives from law, but is not itself law. It is a policy of government that dictates Civil Aviation Medicine’s approach to mental health issues. This policy may be defensible as law if it is ‘authorized by statute’ (Greater Vancouver Transportation Authority, para. 65). The above analysis, however, shows that CAM has created a policy that offends its enabling legislation, the Canadian Aviation Regulations. As such, CAM’s policy is not authorized by statute, so its discriminatory conduct cannot be protected by the Charter.

Even if its conduct were protected by the Charter, CAM’s policy does not balance subjects’ right to equality with a very legitimate interest in aviation safety.

The need for balance is prescribed by the venerable Oakes test:

- The objective of the law must be pressing and substantial (aviation safety is pressing and substantial);

- A rational connection must exist between the law and the objective (one does exist in this case);

- The law must be minimally impairing (the law in this case is minimally impairing; CAM’s policy is not);

- The law’s effect on subjects must be proportional to the social benefit derived from the infringement of subjects’ rights (the law in this case is proportional; CAM’s policy is not).

These latter categories create difficulty for Civil Aviation Medicine because any justification of doctors’ conduct requires an admission of disregard for the affected population or a plea of ignorance that arises from a lack of adequate aeromedical specialization in mental health issues.

Minimal impairment is not a difficult standard; it’s the standard of a decent, rational professional. This professional’s knowledge extends to the context in which they work and in which their field is situate. Civil Aviation Medicine, for example, is populated by doctors, whose medical knowledge also allows them to understand the limits of their expertise. These doctors are literate, and have knowledge of the regulatory context in which they work. They are also able to conduct further research on matters related to their duties, whether those be evaluating applicants for medical certification or crafting policy. Keeping to their creed, doctors also advocate for patients to the best of their ability.

This synopsis derives from Canadian jurisprudence regarding minimal impairment. The courts require government to show that it has chosen a policy from a range of reasonable alternatives (Health Services, para. 150). Enhancing the administration of a government program is not minimally impairing, even if such enhancement might benefit a greater population (Health Services, para. 151). The government must instead show that it considered its policy alternatives with regard for the interest of the affected population (Health Services, para. 150; Charkaoui, paras. 76, 86). When government action is being challenged, analogies may be drawn between the duty to accommodate under human rights law and Charter violations to show whether the government did its utmost to protect minority interests (Multani, para. 53). Minimal impairment may, moreover, be made out with reference to other jurisdictions (such as Australia) and to other international treaties to which Canada adheres (Carter, paras. 103-4; JTI Macdonald, para. 10; Whatcott, para. 67).

Civil Aviation Medicine’s current policy fails to show regard for applicants’ interest as a group that is potentially disadvantaged by CAM’s current practise. The practise of assuming that an applicant presenting with a mental health condition is immediately unfit to fly is inductive. It applies a group characteristic (in this case, a stigma) to more efficiently process medical certification applications. I am told that CAM processes over 50,000 of these a year: the current staff have to keep up. The implication of this statement is clear. Applications may be moved along faster than needed to ensure that the system runs smoothly; the courts do not tolerate this excuse. Analogies between the duty to accommodate and CAM’s practices also point to the problem. CAM does not accommodate in the initial phase of an application, where a person’s safety record is not yet in evidence. Accommodation only occurs after Transport Canada has stigmatized the applicant, and this is no accommodation at all if the applicant could have been assessed as medically fit.

Canada’s international obligations overwhelmingly support a more enlightened approach to mental health in aviation. The United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights guarantees a right to equality (article 1) and freedom from discrimination (article 7), subject only to ‘such limitations as are determined by law’ (article 29). The United Nations’ High Commissioner for Human Rights reported in 2017 that: ‘the experience of living with mental health conditions is shaped, to a great extent, by the historical and continuing marginalization of mental health in public policy’ (para. 14). The Commissioner went on to say that:

This stereotyping, prejudice and stigmatization is present in every sphere of life, including social, educational, work and health-care settings, and profoundly affects the regard in which the individual is held, as well as their own self-esteem. The lack of systematic training and awareness-raising for mental health personnel on human rights as they apply to mental health allows stigma to continue in health settings, which compromises care.

…

The full participation of affected communities in the development, implementation and monitoring of policy has a positive impact on health outcomes and on the realization of their human rights. Ensuring their participation supports the development of responses that are relevant to the context and ensures that policies are effective. Participation in lawmaking and policy design in mental health has typically been directed at health professionals, as a result of which the concerns and views of users, persons with mental health conditions and persons with psychosocial disabilities have not been systematically taken into account and harmful practices have been perpetuated and institutionalized in law and policies.

Paras. 16, 43.

ICAO, an organization based in Montreal, is closely affiliated with the United Nations. Its membership requires that a state also possess membership in the United Nations (Chicago Convention, art. 93 bis). UN members are subject to human rights obligations stemming from the UN; ICAO’s membership is subjected to those obligations. Medical standards promulgated under the Chicago Convention must therefore accord with international human rights obligations.

The last phase of the Oakes test balances the effect of a practise on individuals with its positive outcome for the general population (Frank, para. 76; KRJ, paras. 77-8).

The effects of CAM’s practise have been noted above. Their rehearsal here is only to note that the treatment of mental health conditions afforded to prospective and actual pilots and air traffic controllers can have life-altering consequences. Discrimination and perceived discrimination violate a person’s dignity and can impact her or his self-esteem. More critically still, CAM’s treatment may worsen a person’s mental health. Professional pilots and air traffic controllers may lose their livelihoods, which is a stressor that impacts mental health. It only takes a few words to capture these consequences, but for those affected by mental health conditions, the ramifications are much broader. The stigma still associated with mental health is, as noted above, enhanced when it is directed by the impersonal face of government. Individual well-being is seriously undermined.

The social benefit derived from such discrimination is minimal at best. Aviation safety is adequately protected when Civil Aviation Medicine turns its attention to the individual applicant in order to assess her or his actual ability. Treating physicians are, moreover, required to report any potential risks to aviation safety. The mechanisms maintain the balance between aviation safety and individual rights. A blanket prohibition that requires applicants to prove their fitness for an exception to that prohibition only serves to make Civil Aviation Medicine’s case processing more efficient. It does not address the legitimate aviation safety concerns that benefit society.

The effect of CAM’s policy is, then, far more dire than further adjustments to its policy.

Check out a.p.strom’s aviation law practise

This post is cross-posted to CanLII.

The Law Society of Ontario occupies a special place in most lawyers’ hearts, and much talk has sprung up in recent years about how that special place first forms, then concatenates. One reason that springs to mind among the next crop of legal advisers is that articling students are not represented in the Law Society’s structure. They are, to be sure, members of the Society—no one would deny an opportunity to double down on the costs associated with legal licensing. They are simply not represented.

Before attending to the employment concerns that are the heart of this piece, notice the LSO’s structure. It is, as I have said elsewhere, an eleemosynary corporation with collegial powers:

the Law Society is a professional college that bears the hallmarks of an eleemosynary corporation. It is a foundation endowed to preserve its members’ interests. It can award university (collegiate) degrees. Its funds are (notionally) diverted to its members. The Society is, in other words, a charity designed to house legal professionals as a self-regulating and self-training college, thus maintaining an independent profession.

The nature of this independence (and I have called that independence into question) is as a body corporate consisting of all members of the legal profession. This corporate identity is not a facile construction; it was applied from the ancient collegiate model to house each lawyer, thus giving lawyers rights and obligations toward each other. When we speak of the LSO, therefore, we are referring to the corporation of all lawyers in Ontario, and the place of each lawyer in this structure is, like it or not, that of a participant in the LSO’s good and bad works.

On to the employment matters: the situation becomes more interesting still when you attend to an articling student’s options under the Employment Standards Act. They have none because students-at-law are exempted from employment standards:

2. (1) Parts VII, VII.1, VIII, IX, X and XI of the Act do not apply to a person employed,

(a) as a duly qualified practitioner of, …

(ii) law, …

(e) as a student in training for an occupation mentioned in clause (a), (b), (c) or (d).

If you’re not familiar with the ESA, the above exemptions relate to:

- Hours of work and eating periods;

- The ‘three-hour rule’, which requires an employee who comes to work to be paid at least three hours;

- Overtime pay;

- Minimum wage;

- Entitlements for public holidays; and

- Vacation with pay.

In short, then, students-at-law benefit from none of the rights that are traditionally associated with employees. Their only recourses against employers are through human rights tribunals, the courts, or the Law Society itself.

This recital should give you pause. A profession that prides itself on the honourable and efficient administration of justice would, one thinks, admit vulnerable populations like articling students to basic employment protections.

The legislative and regulatory web, however, make students incredibly vulnerable, and the profession’s regulator is Shelob.

Only one legislated recourse is open to this vulnerable population: unionization. The immediate objection to such a course is that students can’t unionize. That claim to student status mitigates attempts to unionize.

I have, however, elsewhere detailed how students and quasi-students may unionize against universities. This class is virtually identical to the students-at-law toiling in enforced obscurity. My article detailing how doctoral candidates might unionize observed that:

The Employment Standards Act precludes doctoral candidates from the benefits of minimal employment standards. The Labour Relations Act in Ontario has no such quibbles.

Indeed, some unions already represent articling students in the Province of Ontario. Legal Aid Ontario, for example, has its articling students represented by the Society of United Professionals.

The stumbling block when it comes to unionizing articling students against the LSO is that they are perceived as students, not as employees. They are, moreover, not directly employed by the LSO: their ability to unionize must attach to an employment relationship.

The LSO as employer

Careful attention to the LSO’s rules regarding articles of clerkship and judicial opinion on the subject suggests that an employment relationship does exist, which merits collective bargaining. The LSO acts either as a statutorily recognized employer bargaining agency or as a personnel agency with the power to establish employment conditions on behalf of its members (Ontario’s lawyers). Its current rules are not subject to negotiation because the equivalent employee bargaining agency doesn’t exist; it has never been viewed as a personnel agency, likely because its august character doesn’t make the inference obvious. One thing, however, is perfectly clear: articling students and law students don’t have a place at the table despite their entreaties.

An employer or an employee bargaining agency differs from a traditional union because it represents the collection of independent bargaining power for a class of employers or unions. The prime example is the Ontario Hospital Association, which negotiates province-wide terms of employment for nurses and other hospital staff. Local negotiations between individual hospitals in the system also take place to ensure that local peculiarities are satisfied. The provincial agreement, however, predominates.

Where a personnel agency exists, its foremost role is routing job seekers to employers. I should note that employees of temporary help agencies in Ontario receive more statutory protection than articling students. Temporary help agencies also cannot charge employees fees for assigning employees to an employer. The LSO charges its articling students $2,800 for the privilege of being employed. Recall that these fees are charged on top of three years’ worth of exorbitant law school tuition fees.

These observations come to naught if the LSO cannot be made out to be an employer, and my first analytical point must demonstrate that the LSO fits the broad legal definition of an employer. Once this point is established, the right to unionize flows from the Labour Relations Act, which defines ‘employee’ as including ‘a dependent contractor’. No further qualification is given. The word speaks for itself.

The employer relationship

The employer relationship is subject of frequent debate, especially as the gig economy enters full swing. Courts have often pronounced on the true status of an independent contractor under employment standards legislation. Labour Relations Boards have also opined on employee status in the context of union certification. Lord Denning’s view of an employer-employee relationship is most apposite: you know it when you see it. This approach is Canadian courts’ and tribunals’ final position in the helter skelter world of judicial opinion.

I’ll dredge up some Labour Relations Board commentary:

The difficulty posed by cases like those of articling students, medical residents and graduate students is that the licensing or academic requirements imposed by an entity upon the individual seeking to be licensed or graduate may serve to explain all or some hallmarks of a relationship which would otherwise be an employment relationship with that entity: direction and control, performance of work, production of something of value, and receipt of income.

CUPE v Governing Council of the University of Toronto, para. 88.

This difficulty is, of course, squarely at issue for articling students. The five hallmarks of an employment relationship are present. The major stumbling point is that each of the five hallmarks may also be assigned to the lawyer or firm employing an articling student. The traditional view, and one that has been assumed by the courts, aids the law societies. In the LSO’s case, there appears to be no challenge to the bald disclaimer in its licensing process policy:

The Society is not a party to the employment relationship created by Articles. The employment relationship is between the Candidate and the Candidate’s employer.

Art. 10.3.

This statement doesn’t hold water if the LSO is found to have all the hallmarks of an employment relationship.

Canadian cases go a ways toward defining the employment relationship, but the law is fraught with discordance. Several tests exist such that the traditional test for control, which defined a master-servant employment relationship is no longer persuasive. Two other tests may apply to the LSO’s relationship with articling students.

The first of these is the fourfold test. This test requires a sufficient degree of control, the ownership of tools, a chance of profit, and a risk of loss.

The second is the organization test, which asks whether a person or group is part of the employer’s organization. The judicial emphasis is placed on the location and timing of the work If the person is indeed part of the organization, they are employees.

Supreme Court Justice Major stated the test more plainly in 671122 Ontario Ltd. v. Sagaz Industries Canada Inc.:

In my opinion, there is no one conclusive test which can be universally applied to determine whether a person is an employee or an independent contractor. …

The central question is whether the person who has been engaged to perform the services is performing them as a person in business on his own account. In making this determination, the level of control the employer has over the worker’s activities will always be a factor. However, other factors to consider include whether the worker provides his or her own equipment, whether the worker hires his or her own helpers, the degree of financial risk taken by the worker, the degree of responsibility for investment and management held by the worker, and the worker’s opportunity for profit in the performance of his or her tasks.

It bears repeating that the above factors constitute a non-exhaustive list, and there is no set formula as to their application. The relative weight of each will depend on the particular facts and circumstances of the case.

Paras. 46-8.

The flexibility of Justice Major’s position has been the Ontario Labour Relations Board’s practise. In C.J.A., Local 27 v. Calvano Lumber & Trim Co., a panel said that:

Employment relationships may exhibit a variety of forms in different contexts, but the essence of such relationship is the exchange of labour for consideration in some form. Collective bargaining concerns the terms of that exchange and trade union representation permits even small groups of employees to improve them.

Applying helter skelter

The LSO’s rules relating to articling students disclose a level of control over the articling relationship that, though not undue, points to students’ status as labour.

The test for control is an obvious starting point. Lawyers control articling students’ day-to-day activities. That control, however, springs from lawyers’ relationship to the LSO. All articling supervisors are approved by the LSO and are regulated as delegates of the LSO. This regulation is akin to appointing professors to supervise graduate students. The lawyer works at the LSO’s behest, and her or his payment for this service is the provision of labour from the LSO. The relationship between the LSO and its students, then, is colourable by the control that the Society exercises over principals.

This point is enhanced by the Society’s potential control over the process. Its recent decision to compel principals to pay their students is a case-in-point. The Society can establish any term or condition relating to students’ labour, thus giving it unlimited potential to control the relationship. That potential, or the ability to control the work, is a determining factor in the test (see 2017 TCC 242, para. 16; Zacharuk v. Kitlarchuk, paras. 20-1).

The fourfold test builds on this analysis. The LSO’s control is established. The ownership of tools rests with the principal, but the tools for a modern lawyer are minimal. A computer is needed, and access to a couple paid databases is helpful. Most of the resources necessary for a lawyer’s trade may be found in a well-stocked university law library. The principal has a chance of profiting on the student’s work; the LSO obtains profit from the student by charging fees to give the student access to the working relationship. This structure, of course, does not import a risk of loss. The LSO instead deputizes its members as agents on its behalf. The risk of loss is passed onto the individual member. Those members are, however, extensions of the LSO’s corporate personality. Their rights and privileges are determined and allowed by each other lawyer, which implies that the risk passed to an individual lawyer is one authorized by the profession. My interpretation is preserved by the above-noted relationship between LSO and principal.

The fourfold test for an employment relationship between articling student and LSO is thus fulfilled. The LSO exercises control over the student’s work; though it does not supply any tools for the work, not many are needed in most cases; it obtains profit from the worker; and it has passed the risk of loss on to individual members.

This assessment of the LSO’s work makes the organization test a formality. The above analysis suggests that the Society serves as a temporary employment agency. It creates the sole means of entering the profession and requires workers to comply with its organizational rules before complying with articling principals’ local requirements. The eleemosynary nature of law societies, moreover, means that each principal is complicit in establishing and maintaining the scheme. The college’s directing minds directly benefit from the organization’s decision to raise labour by using its statutory privileges.

There exists, moreover, a policy reason for recognizing Ontario’s articling students as employees of the LSO. Such recognition allows them to have a meaningful voice in the profession that has so far refused to accede to requests for representation. The Ontario Labour Relations Board recognized this fact in Association of Commercial and Technical Employees, Local 1704 v Parkdale Community Legal Services:

In view of their exclusion from the definition of “member” of the Law Society as set out above, articling students are unable to participate in the governing process of the Society either through voting for or becoming a bencher.

…

to give “member” under The Labour Relations Act a broader interpretation than “member” under The Law Society Act would be to exclude form collective bargaining persons who are not yet full members of their profession and can neither enjoy the full benefits of their professional association nor have an effective input into its operation. The existence of professional associations and an assumed lack of need for collective bargaining among their members provides a fundamental pillar of support for the professional exclusion under The Labour Relations Act. In the absence of clear language to the contrary, we are not persuaded that the Legislature intended to exclude from collective bargaining persons who still stand at the door of their profession and, until they become full members of their professional association, lack effective means of self determination through that association.

Paras. 11, 13.

The fees levied against articling candidates entitle them to a measure of responsible government. If the LSO is unwilling to provide such a measure, the Labour Relations Board is the best alternative.

Conclusion

There’s much left to be said and done on this issue. The above sketch will hopefully generate more in-depth discussion regarding articling students’ place as labourers in the profession. Steps may be taken to organize union representation, either directly against the Law Society, or in concern with unions to form a provincial bargaining association.

The way forward in this regard is fraught by the ever-changing nature of the workforce. Articling students only work for ten months before moving on to professional life. A successful unionization drive therefore requires a rapid vote to certify the bargaining unit, or a vote that is so public that incoming articling students are aware of the issues and can feel confident voting for representation.

The challenge isn’t for the faint of heart, but when one attends to stories of articling relationships gone wrong, or when one takes cognizance of the LSO’s inflexible criteria with regard to this labour pool, the vulnerability of the articling student population to a hierarchical and arcane professional regulator’s decisions is striking.

Elected oversight of municipal (or provincial) police forces is, as I indicated in my previous post, a difficult system by which to enforce standards on police. Foremost among the difficulties of this system: the relative lack of enforcement power granted to these boards. A corollary difficulty is the civilian nature of the oversight. Lack of power and civilians’ frequent inexperience with the machinations of judicial power make civilian oversight a tepid solution to the concerns that are currently being raised about police forces.

The Toronto example from my previous post is low-hanging proof of these difficulties. Justice Iacobucci’s recommendations following the Toronto Police Services’ killing of Sammy Yatim were left mostly unimplemented by the Board one year after the report came out. The limited powers of police oversight boards in Ontario are largely to blame; the remaining blame must fall to the Board itself. What powers exist for the Board to exercise, notably the power to instruct the police chief on matters relating to the department, is legislative and discretionary. These words mean that few legal tools exist to review a police board’s decisions.

Canadian history, however, shows that more responsive models exist; these, however, are not prefaced by the shibboleth: ‘elected oversight’.

One system widely used in nineteenth-century Canadian policing involved police magistrates (essentially justices of the peace) exercising supervision over police constables. This system operated in straight judicial fashion. The magistrate of a police force directly supervised and sanctioned constables, and held the post to the exclusion of other positions.

The benefit of such keen oversight cannot be overstated: a single official sits in appeal of policing decisions, and a single official has all judicial powers necessary to require police to comply with her or his decisions.

This system is, of course, dated, and it was roundly criticized in the Ontario legislature as late as 1962, where Liberal MPP Elmer Sopha said that:

There is in short no justification for the continuation of this practise in this province. Let us get the magistrates away from their connection with the police depar[t]ment. Then you will see one corrective and prophylactic effect it will have on the administration of justice. If they are not connected with the magistrate, you will find that the policemen in their conduct will–those few who are guilty of mis-behaviour, and perhaps guilty of brutality towards citizens–will indeed be more wary of having their conduct reviewed before a magistrate who occupies the independent position that I posit.

Ontario Legislative Assembly, Official report of debates, 4th Sess., 26th Legis., p. 992.

A countervailing view was later posited in 1979 by Norman W. Sterling, a progressive conservative member of the Standing Committee on the Administrative of Justice:

It might be interesting to go back in history some time. Originally, a board of commissioners was first appointed prior to Confederation. In the early days, a police magistrate was a member. In the year after Confederation, in 1868, a county court judge was appointed at that time. So for some 110 or 111 years we have had the county court judge as a member of the police commission.

The members of the municipal police force are governed and directed by the police board. This body is designed to ensure that the police are independent of direct political control of the municipality. The autonomy of the police boards, in my view, is essential to the proper administration of justice. This independence would be lessened if the police officials were either directly controlled by the municipally elected officials or were, in fact, municipally elected officials.

Ontario Legislative Assembly, Official report of debates, 3 Sess., 31st Legis., p. 1796.

These competing views are alive today, and they animate this post: judges ought not try cases in which they have participated in a non-judicial capacity; municipal officials (presently appointed to Ontario police boards) should not sit on such boards because they inject municipal politics into policing.

Lessons from history, however, indicate that we might resolve this tension by appointing a senior justice of the peace in each county or municipality as a police magistrate. This officer would be barred from hearing cases of police misconduct during the course of criminal proceedings; he would instead investigate and adjudicate all matters relating to police misconduct as separate cases. For those who insist on the shibboleth, two municipally appointed lay assessors would assist the magistrate in each case (my grandfather served as a lay assessor in Sweden).

This solution is not elected oversight. It is instead judicial oversight designed for quick responses to police misconduct. The rationale behind this proposal will be revealed with reference to some historical texts.

Historical sources

The police magistrate before Confederation was an omnipotent official that served as a specialized justice of the peace. One source describes the magistrate as a municipal official tending to local concerns:

A Police Magistrate, in the eyes of the law is nothing but two Justices of the Peace rolled into one, who is paid to see, among other things, that the by-laws of his city or town are kept inviolate.

Wicksteed, R.J. The Inferior Magistrates, or, Legal Pluralism in Ontario. Early Canadiana Online 25765, 1886, p. 2

To this definition must be added a more general oversight of policing. The system was inherited from England, where justices of the peace chose constables to keep the peace:

the usuall manner is, that these High Constables of Hundreds be chosen either at the quarter Sessions of the peace; or if out of the Sessions; then by the greater number of the Justices of peace of the Division where they dwell.

Dalton, Michael. The Countrey Justice Containing the Practice of the Justices of the Peace out of Their Sessions. 5th ed. EEBO, STC (2nd ed.) / 6210. London: John More, 1635, cap. 16.

High Constables would, in conjunction with the justices, select further constables for keeping the peace.

Through developments and export, the official evolved such that special magistrates were appointed to oversee police, but justices continued to be involved in appointing police:

The Constable is a Peace Officer generally chosen by the Justices at their Quarter Sessions, and is the proper Officer to a Justice of the Peace, and bound to execute his warrants.

Taylor, Hugh. Manual of the Office, Duties and Liabilities of a Justice of the Peace. Early Canadiana Online 43246. Montreal: Armour & Ramsay, 1843, p. 130; see also, Dempsey, Ricahrd. Magistrate’s Hand-Book. Early Canadiana Online 49619. Toronto: Rowsell & Ellis, 1860, p. 40.

Newfoundland, moreover, explained the relationship between police and all judicial officers in legislative terms:

The Magistrate, however, is responsible to the government for the maintenance of good order within his district, the detection of crime, arrest of criminals, and generally the carrying out of the law—very large powers and authority are given to Magistrates by Imperial and Local Acts. The Policeman is the Executive Officer of Justice, and he must attend to all lawful orders of the Magistrate and obey them implicitly, he should also attend strictly to all suggestions of the Magistrate in carrying out the law ; he should keep his worship fully informed of all matters of a public nature that come to his knowledge.

Prowse, Daniel Woodley. The Justices’ Manual, or, Guide to the Ordinary Duties of a Justice of the Peace in Newfoundland. 2nd ed. Early Canadiana Online 67826. St. John’s, Nfld: 1898, p. 118.

These sources identify two bonds between justices and constables or police officers. The first is that justices of the peace, the judicial officers closest to their communities, have historically been involved in the appointment of police. The second is that police are agents of the courts, which agency requires them to heed not only judicial decisions, but expressions of judicial policy about policing.

This system endured, but admitted increasing elected oversight such that, by 1970, the mayor of a municipality sat with a provincial court judge and a provincial appointee as municipal police boards. These boards had sweeping power to appoint and dismiss officers, to enact by-laws for the management of the police force, and to summon witnesses under oath. These powers stem in part from the judicial powers that have animated police appointments and police control through the ages.

The judge had, by 1980, been removed from the composition of police boards; a second provincial appointee took the judge’s place, thus ending judicial involvement in direct police oversight.

Oversight maintained

Balancing the benefits of elected oversight with judicial power

This system of appointing and supervising police has, of course, now changed. There is a firm division between judicial authority and police forces. The noises that led to this shift may be heard in Mr. Sopha’s comments to the Legislative Assembly in 1962.

The separation of powers is, indeed, an important republican principle; trust between subject and government is an essential part of a constitutional monarchy.

Appointing a justice of the peace to sit with two lay assessors effectively balances these preoccupations. The justice is the emanation of judicial power over police conduct; the lay assessors are appointed by elected officials, so represent elected oversight.

Reunifying judicial oversight with police forces emphasizes the central role of any policeman, which is defined by Daniel W. Prowse in his treatise on Newfoundland justices:

The constable will always remember that the object of arresting a prisoner is to bring him before a Magistrate as soon as he reasonably can.

p. 118, emphasis original.

The problem and our typical solution

This analysis of police supervision in Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States will appear in two parts. The first part breaks down the problem with civilian policing oversight; the second part addresses the issue with reference to English precedents that were received in Canada and the United States.

Much has been said about defunding police forces and putting those funds to better use sustaining developmental and social services. There is a further, less discussed, need to rethink the management and oversight of police services.

This oversight, though a noble nod toward democratic ideals, has come under pressure at a time when police forces are mistrusted by minority populations. This phenomenon sweeping United Kingdom, Canadian, and American jurisdictions evokes the ages-old debate between technocrats and idealists, or philosopher-kings and democrats.

The slogan ‘defund the police’ paints this issue in stark terms, but the sentiment is pure: cops have been observed committing gross abuses. Even if these are never proven in a legal sense, they diminish respect for and trust in the state’s judicial apparatus.

Militarization of policing is one side of this coin; we might shine more light on the supervision of militarization under civilian police boards. The pattern that may be observed across an admittedly small sampling of police forces is that civilian oversight is often reticent to engage (for one reason or another) with the police forces over which they supposedly lord. This inability to engage has, I think, been missed in the current discussion of police violence and the police’s role in communities. Shining a light in this limited series may help spur some reflection on how we would like our police to be better held to account.

Case study

My home of Ottawa has served as a recent example of the perils of civilian oversight. Civilians are no guaranteed experts, nor are they remotely impartial judges. In Ottawa’s case, a group drawing attention to injustices perpetrated against indigenous and black subjects was forcibly removed by police hours before meeting with members of the Ottawa Police Services Board. The group refused to meet with the Board after arrests were made. The Board’s response to these events stated that it did not interfere in the police service’s operational decisions. The timing of the police’s intervention remains suspect.

Part of this issue lies with the Board’s statutory inability to interfere in the police’s operational decisions. This common prohibition is counterweighed by the Board’s investigative and regulatory power, which can be deployed in cases where unfair behaviour might undermine judicial or police authority. No questions appear to have been asked of Ottawa’s police chief by the Board.

The Board, moreover, failed to uphold one of the principles underpinning policing in Ontario: ensuring that subjects’ constitutional rights are upheld. Justice Marlyse Dumel dismissed a drunk driving case because officers failed to respect the accused’s right to counsel. The Justice noted that there was no police regulation that required arresting officers to be informed that their cases were dismissed due to breaches of Canadian constitutional rights. The Board is aware of this problem, but the police chief failed to propose—and Board members do not seem to have asked for—any further measures to ensure Ottawans’ constitutional rights are respected.

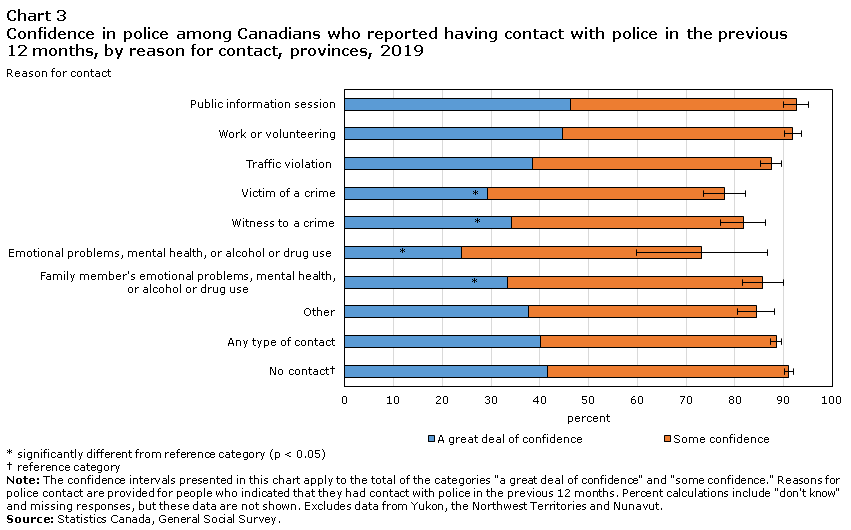

Taking a wider view of Ottawa’s police service in Canadian context also shows that vulnerability to police discretion is likely to lessen a person’s confidence in the police force. Keep in mind that vulnerability is likely to make anyone more critical of authority; know also that authorities with data in hand can take more meaningful steps toward fostering empathy. Statistics Canada’s annual data for public perceptions of police shows that interactions between victims, witnesses, and those suffering from atypical behaviour and police are less likely to produce trust in police.

Subjects with disabilities were similarly less likely to trust police. Visible minorities reported perceiving police as treating people fairly 34% of the time; non-visible minorities reported 45% under the same heading. The data also shows that Canadians aged forty-five years or older tend to trust police more than those below forty-five.

Building public trust on these numbers requires broad appeal to sometimes divergent demographics. Police services boards can temper differences between police culture and vulnerable groups’ experiences.

The Ottawa Police Service’s lacunae are not trifling things, nor are they wholly beyond civilian oversight, as the Ottawa Police Services Board suggested by evoking operational decisions. Proactive and reactive oversight is needed to ensure that operational decisions are in line with community and legal values. This kind of work is community building in its most elementary sense, and Ottawa’s Police Services Board fell below the mark when it failed to publicly inquire into the reasons for the police’s arresting protestors on the eve of their meeting Board members.

The United States

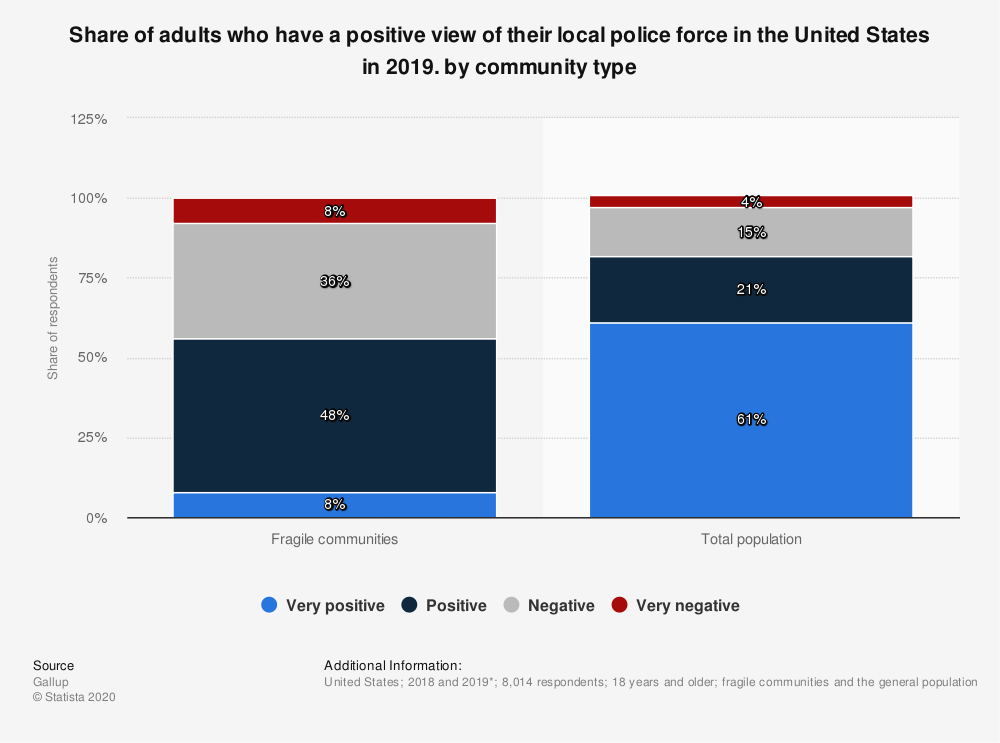

Lest these statistics and problems seem remote or too local, the United States’ national numbers for trust in police are even more grim. The total population may, for the most part, trust police. Vulnerable communities in the United States exhibit far less trust.

These numbers are complimented by a marked lessening of trust from Generation Z. This generation’s trust in US police dropped from 56% in June 2019 to 44% in June 2020.

The erosion of trust, which has obviously manifested in protests across the US and in Canada, has prompted American authorities to turn toward democratically elected police oversight. Fort Worth, Texas, announced such a change on December 2, 2020. Ballot box initiatives in San Jose, Los Angeles, Portland, Seattle, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Columbus instituted enhanced civilian oversight.

American county governments’ extant powers over policing do not exhibit much civilian oversight. Sheriffs are typically elected and thus derive authority directly from the electorate, whose oversight comes solely in the form of elections. State and federal police forces may have the right to lay charges, but these rights are relatively limited by the burden of proof.

The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s department (not to be confused with the LAPD, which is a municipal force overseen by police commissioners), for example, is led by an elected sheriff. Though this sheriff must possess minimal qualifications, the County’s Board of Supervisors has no power over the sheriff. The Board can only ‘direct the sheriff to attend, either in person or by deputy, all meetings of the board, to preserve order, and to serve notices, subpenas, citations, or other process, as directed by the board’ [sic].

The movement toward civilian oversight in the United States is encouraging if not timely. Its relevance as an effective force for cultural changes that can build badly eroded trust in communities remains to be seen.

Elected oversight