Elected oversight of municipal (or provincial) police forces is, as I indicated in my previous post, a difficult system by which to enforce standards on police. Foremost among the difficulties of this system: the relative lack of enforcement power granted to these boards. A corollary difficulty is the civilian nature of the oversight. Lack of power and civilians’ frequent inexperience with the machinations of judicial power make civilian oversight a tepid solution to the concerns that are currently being raised about police forces.

The Toronto example from my previous post is low-hanging proof of these difficulties. Justice Iacobucci’s recommendations following the Toronto Police Services’ killing of Sammy Yatim were left mostly unimplemented by the Board one year after the report came out. The limited powers of police oversight boards in Ontario are largely to blame; the remaining blame must fall to the Board itself. What powers exist for the Board to exercise, notably the power to instruct the police chief on matters relating to the department, is legislative and discretionary. These words mean that few legal tools exist to review a police board’s decisions.

Canadian history, however, shows that more responsive models exist; these, however, are not prefaced by the shibboleth: ‘elected oversight’.

One system widely used in nineteenth-century Canadian policing involved police magistrates (essentially justices of the peace) exercising supervision over police constables. This system operated in straight judicial fashion. The magistrate of a police force directly supervised and sanctioned constables, and held the post to the exclusion of other positions.

The benefit of such keen oversight cannot be overstated: a single official sits in appeal of policing decisions, and a single official has all judicial powers necessary to require police to comply with her or his decisions.

This system is, of course, dated, and it was roundly criticized in the Ontario legislature as late as 1962, where Liberal MPP Elmer Sopha said that:

There is in short no justification for the continuation of this practise in this province. Let us get the magistrates away from their connection with the police depar[t]ment. Then you will see one corrective and prophylactic effect it will have on the administration of justice. If they are not connected with the magistrate, you will find that the policemen in their conduct will–those few who are guilty of mis-behaviour, and perhaps guilty of brutality towards citizens–will indeed be more wary of having their conduct reviewed before a magistrate who occupies the independent position that I posit.

Ontario Legislative Assembly, Official report of debates, 4th Sess., 26th Legis., p. 992.

A countervailing view was later posited in 1979 by Norman W. Sterling, a progressive conservative member of the Standing Committee on the Administrative of Justice:

It might be interesting to go back in history some time. Originally, a board of commissioners was first appointed prior to Confederation. In the early days, a police magistrate was a member. In the year after Confederation, in 1868, a county court judge was appointed at that time. So for some 110 or 111 years we have had the county court judge as a member of the police commission.

The members of the municipal police force are governed and directed by the police board. This body is designed to ensure that the police are independent of direct political control of the municipality. The autonomy of the police boards, in my view, is essential to the proper administration of justice. This independence would be lessened if the police officials were either directly controlled by the municipally elected officials or were, in fact, municipally elected officials.

Ontario Legislative Assembly, Official report of debates, 3 Sess., 31st Legis., p. 1796.

These competing views are alive today, and they animate this post: judges ought not try cases in which they have participated in a non-judicial capacity; municipal officials (presently appointed to Ontario police boards) should not sit on such boards because they inject municipal politics into policing.

Lessons from history, however, indicate that we might resolve this tension by appointing a senior justice of the peace in each county or municipality as a police magistrate. This officer would be barred from hearing cases of police misconduct during the course of criminal proceedings; he would instead investigate and adjudicate all matters relating to police misconduct as separate cases. For those who insist on the shibboleth, two municipally appointed lay assessors would assist the magistrate in each case (my grandfather served as a lay assessor in Sweden).

This solution is not elected oversight. It is instead judicial oversight designed for quick responses to police misconduct. The rationale behind this proposal will be revealed with reference to some historical texts.

Historical sources

The police magistrate before Confederation was an omnipotent official that served as a specialized justice of the peace. One source describes the magistrate as a municipal official tending to local concerns:

A Police Magistrate, in the eyes of the law is nothing but two Justices of the Peace rolled into one, who is paid to see, among other things, that the by-laws of his city or town are kept inviolate.

Wicksteed, R.J. The Inferior Magistrates, or, Legal Pluralism in Ontario. Early Canadiana Online 25765, 1886, p. 2

To this definition must be added a more general oversight of policing. The system was inherited from England, where justices of the peace chose constables to keep the peace:

the usuall manner is, that these High Constables of Hundreds be chosen either at the quarter Sessions of the peace; or if out of the Sessions; then by the greater number of the Justices of peace of the Division where they dwell.

Dalton, Michael. The Countrey Justice Containing the Practice of the Justices of the Peace out of Their Sessions. 5th ed. EEBO, STC (2nd ed.) / 6210. London: John More, 1635, cap. 16.

High Constables would, in conjunction with the justices, select further constables for keeping the peace.

Through developments and export, the official evolved such that special magistrates were appointed to oversee police, but justices continued to be involved in appointing police:

The Constable is a Peace Officer generally chosen by the Justices at their Quarter Sessions, and is the proper Officer to a Justice of the Peace, and bound to execute his warrants.

Taylor, Hugh. Manual of the Office, Duties and Liabilities of a Justice of the Peace. Early Canadiana Online 43246. Montreal: Armour & Ramsay, 1843, p. 130; see also, Dempsey, Ricahrd. Magistrate’s Hand-Book. Early Canadiana Online 49619. Toronto: Rowsell & Ellis, 1860, p. 40.

Newfoundland, moreover, explained the relationship between police and all judicial officers in legislative terms:

The Magistrate, however, is responsible to the government for the maintenance of good order within his district, the detection of crime, arrest of criminals, and generally the carrying out of the law—very large powers and authority are given to Magistrates by Imperial and Local Acts. The Policeman is the Executive Officer of Justice, and he must attend to all lawful orders of the Magistrate and obey them implicitly, he should also attend strictly to all suggestions of the Magistrate in carrying out the law ; he should keep his worship fully informed of all matters of a public nature that come to his knowledge.

Prowse, Daniel Woodley. The Justices’ Manual, or, Guide to the Ordinary Duties of a Justice of the Peace in Newfoundland. 2nd ed. Early Canadiana Online 67826. St. John’s, Nfld: 1898, p. 118.

These sources identify two bonds between justices and constables or police officers. The first is that justices of the peace, the judicial officers closest to their communities, have historically been involved in the appointment of police. The second is that police are agents of the courts, which agency requires them to heed not only judicial decisions, but expressions of judicial policy about policing.

This system endured, but admitted increasing elected oversight such that, by 1970, the mayor of a municipality sat with a provincial court judge and a provincial appointee as municipal police boards. These boards had sweeping power to appoint and dismiss officers, to enact by-laws for the management of the police force, and to summon witnesses under oath. These powers stem in part from the judicial powers that have animated police appointments and police control through the ages.

The judge had, by 1980, been removed from the composition of police boards; a second provincial appointee took the judge’s place, thus ending judicial involvement in direct police oversight.

Oversight maintained

Balancing the benefits of elected oversight with judicial power

This system of appointing and supervising police has, of course, now changed. There is a firm division between judicial authority and police forces. The noises that led to this shift may be heard in Mr. Sopha’s comments to the Legislative Assembly in 1962.

The separation of powers is, indeed, an important republican principle; trust between subject and government is an essential part of a constitutional monarchy.

Appointing a justice of the peace to sit with two lay assessors effectively balances these preoccupations. The justice is the emanation of judicial power over police conduct; the lay assessors are appointed by elected officials, so represent elected oversight.

Reunifying judicial oversight with police forces emphasizes the central role of any policeman, which is defined by Daniel W. Prowse in his treatise on Newfoundland justices:

The constable will always remember that the object of arresting a prisoner is to bring him before a Magistrate as soon as he reasonably can.

p. 118, emphasis original.

The problem and our typical solution

This analysis of police supervision in Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States will appear in two parts. The first part breaks down the problem with civilian policing oversight; the second part addresses the issue with reference to English precedents that were received in Canada and the United States.

Much has been said about defunding police forces and putting those funds to better use sustaining developmental and social services. There is a further, less discussed, need to rethink the management and oversight of police services.

This oversight, though a noble nod toward democratic ideals, has come under pressure at a time when police forces are mistrusted by minority populations. This phenomenon sweeping United Kingdom, Canadian, and American jurisdictions evokes the ages-old debate between technocrats and idealists, or philosopher-kings and democrats.

The slogan ‘defund the police’ paints this issue in stark terms, but the sentiment is pure: cops have been observed committing gross abuses. Even if these are never proven in a legal sense, they diminish respect for and trust in the state’s judicial apparatus.

Militarization of policing is one side of this coin; we might shine more light on the supervision of militarization under civilian police boards. The pattern that may be observed across an admittedly small sampling of police forces is that civilian oversight is often reticent to engage (for one reason or another) with the police forces over which they supposedly lord. This inability to engage has, I think, been missed in the current discussion of police violence and the police’s role in communities. Shining a light in this limited series may help spur some reflection on how we would like our police to be better held to account.

Case study

My home of Ottawa has served as a recent example of the perils of civilian oversight. Civilians are no guaranteed experts, nor are they remotely impartial judges. In Ottawa’s case, a group drawing attention to injustices perpetrated against indigenous and black subjects was forcibly removed by police hours before meeting with members of the Ottawa Police Services Board. The group refused to meet with the Board after arrests were made. The Board’s response to these events stated that it did not interfere in the police service’s operational decisions. The timing of the police’s intervention remains suspect.

Part of this issue lies with the Board’s statutory inability to interfere in the police’s operational decisions. This common prohibition is counterweighed by the Board’s investigative and regulatory power, which can be deployed in cases where unfair behaviour might undermine judicial or police authority. No questions appear to have been asked of Ottawa’s police chief by the Board.

The Board, moreover, failed to uphold one of the principles underpinning policing in Ontario: ensuring that subjects’ constitutional rights are upheld. Justice Marlyse Dumel dismissed a drunk driving case because officers failed to respect the accused’s right to counsel. The Justice noted that there was no police regulation that required arresting officers to be informed that their cases were dismissed due to breaches of Canadian constitutional rights. The Board is aware of this problem, but the police chief failed to propose—and Board members do not seem to have asked for—any further measures to ensure Ottawans’ constitutional rights are respected.

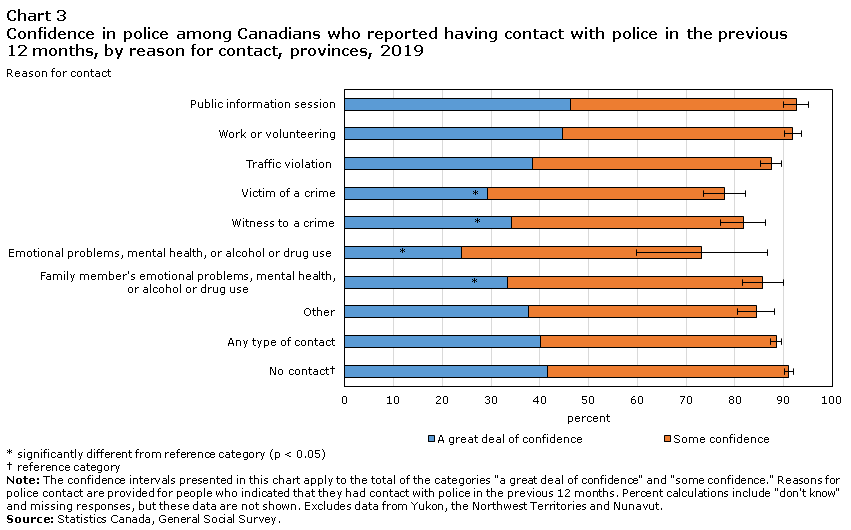

Taking a wider view of Ottawa’s police service in Canadian context also shows that vulnerability to police discretion is likely to lessen a person’s confidence in the police force. Keep in mind that vulnerability is likely to make anyone more critical of authority; know also that authorities with data in hand can take more meaningful steps toward fostering empathy. Statistics Canada’s annual data for public perceptions of police shows that interactions between victims, witnesses, and those suffering from atypical behaviour and police are less likely to produce trust in police.

Subjects with disabilities were similarly less likely to trust police. Visible minorities reported perceiving police as treating people fairly 34% of the time; non-visible minorities reported 45% under the same heading. The data also shows that Canadians aged forty-five years or older tend to trust police more than those below forty-five.

Building public trust on these numbers requires broad appeal to sometimes divergent demographics. Police services boards can temper differences between police culture and vulnerable groups’ experiences.

The Ottawa Police Service’s lacunae are not trifling things, nor are they wholly beyond civilian oversight, as the Ottawa Police Services Board suggested by evoking operational decisions. Proactive and reactive oversight is needed to ensure that operational decisions are in line with community and legal values. This kind of work is community building in its most elementary sense, and Ottawa’s Police Services Board fell below the mark when it failed to publicly inquire into the reasons for the police’s arresting protestors on the eve of their meeting Board members.

The United States

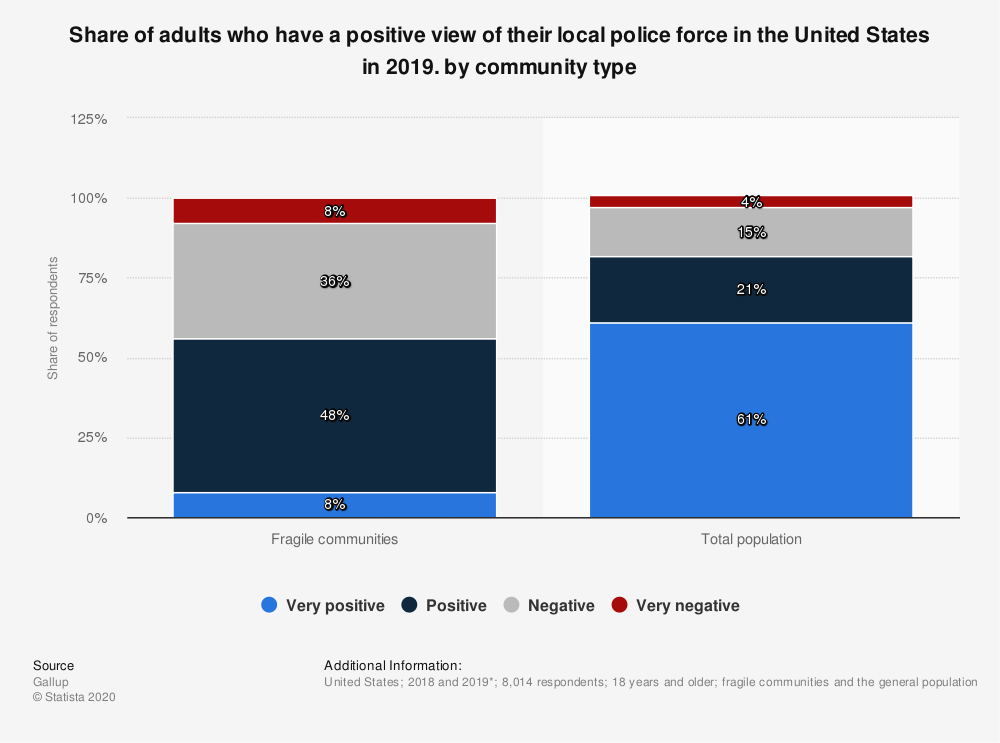

Lest these statistics and problems seem remote or too local, the United States’ national numbers for trust in police are even more grim. The total population may, for the most part, trust police. Vulnerable communities in the United States exhibit far less trust.

These numbers are complimented by a marked lessening of trust from Generation Z. This generation’s trust in US police dropped from 56% in June 2019 to 44% in June 2020.

The erosion of trust, which has obviously manifested in protests across the US and in Canada, has prompted American authorities to turn toward democratically elected police oversight. Fort Worth, Texas, announced such a change on December 2, 2020. Ballot box initiatives in San Jose, Los Angeles, Portland, Seattle, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Columbus instituted enhanced civilian oversight.

American county governments’ extant powers over policing do not exhibit much civilian oversight. Sheriffs are typically elected and thus derive authority directly from the electorate, whose oversight comes solely in the form of elections. State and federal police forces may have the right to lay charges, but these rights are relatively limited by the burden of proof.

The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s department (not to be confused with the LAPD, which is a municipal force overseen by police commissioners), for example, is led by an elected sheriff. Though this sheriff must possess minimal qualifications, the County’s Board of Supervisors has no power over the sheriff. The Board can only ‘direct the sheriff to attend, either in person or by deputy, all meetings of the board, to preserve order, and to serve notices, subpenas, citations, or other process, as directed by the board’ [sic].

The movement toward civilian oversight in the United States is encouraging if not timely. Its relevance as an effective force for cultural changes that can build badly eroded trust in communities remains to be seen.

Elected oversight

The turn toward elected oversight or, indeed, the existence of such oversight is a richly rewarded political move in liberal-democracies. As I’ve indicated above, a tension exists between popular government and government by technocrats. A common lawyer might, perhaps, question such a distinction for its covalence. Technocracy cannot seriously exist in democratic governments. I will address this concern more fully in the second part. Suffice for the present to say that elected police oversight can effectively govern police if elected members are willing to invest time and energy beyond simply meeting to hear citizens’ concerns and deliberate.

Ontario’s current regime provides boards with all the powers necessary to effectively oversee police services. Boards’ oversight is determined by the level of scrutiny each member provides. In the wake of the Toronto Police Service’s killing Sammy Yatim, retired Supreme Court Justice Frank Iacobucci conducted a study that made 94 recommendations to improve Toronto Police’s handling of people in crisis. The Police Services Board’s oversight was not at issue in this review. Justice Iacobucci adverted to this fact:

The Board plays a key role in the democratic oversight of the police, and in ensuring accountability of the police to the community that the police serves. Although I do not make specific recommendations for Board involvement in overseeing the implementation of this Report (because to do so would be beyond my mandate), the Board will undoubtedly have an important oversight role to play.

A year after the Justice released his report, Alok Mukherjee, then just retired from chairing the Toronto Police Services Board, noted that many of Justice Iacobucci’s recommendations had not been implemented. His statement so soon after retiring stands in stark contrast to Justice Iacobucci’s call to action.

New oversight in American jurisdictions and existing oversight in Canadian provinces requires active oversight to be effective. The City of Toronto’s 2014 example is one where active oversight does not seem to have worked: the Chief of Police asked a retired judge to investigate the police service. The judge’s report, though detailed and very considered, was not the product of civilian oversight. The Board’s conduct was thus not in Justice Iacobucci’s scope, nor did he purport to comment upon it.

The City of Ottawa’s Police Services Board is another example of a fairly staid organization defined by its members’ misapprehension of statutory powers. The Board possesses the ability to inquire into police conduct on its city’s behalf; it chose to define itself as a deliberative assembly focused solely on policy. This act of self-definition hems most of the Board’s powers in, leaving the Board with little to inquire upon and still less with which to discipline.

As Americans look at these examples in an effort to implement more civilian oversight of police forces, the lesson is that you get the government that you deserve. Activist groups ought to take sharper aim on their civilian oversight panels, to encourage—to really push these individuals (themselves likely overworked for the positions that they occupy) toward greater oversight. The tone need not be confrontational, but a principled stand needs to bring police oversight to account. Only then can police be adequately overseen.

The next installation of The Judicious Sasquatch will delve into how effective oversight might be accomplished. This analysis will have regard for historical precedents and, as always, an eye toward applying them to strengthen public policy.

Until then (hell, even after the next installation is out), please feel free to engage with this post.

Quebec calls for greater language protection for Canadian federal enterprises

The Parliament of Quebec and the Bloc Québecois have formally requested an extension of cooperative federalism to Quebec language protection. ‘Cooperative federalism’ is a legal principle that has courts interpret legislation in ways that allow federal and provincial laws to work together. The term evokes greater ‘interlocking federal and provincial legislative schemes’. This principle is rejoined by the double aspect principle of interpretation: provincial and federal legislation can touch on the same subject matter from different perspectives.

On November 24, 2020, the Parliament of Quebec passed an unanimous resolution calling on the federal government to apply the Charter of the French Language to public and private federal works and undertakings. Quebec’s request is couched in federal legislative terms. The House of Commons read bill C-254, entitled An Act to amend the Canada Labour Code, the Official Languages Act and the Canada Business Corporations Act, for the first time on the same day. The bill amends the three acts in its title to declare that federal-jurisdiction undertakings respect Quebec’s Charter.

Bill C-254 works with the Quebec Assembly’s resolution to preclude any constitutional challenge to enhanced french language laws in Quebec. This bill is significant because the Conservative party has endorsed its principle. The House of Commons could pass the private member’s bill in short order, if parties were willing.

Federal legislation is the easiest way to accomplish Quebec’s aim. It is not, however, the only way. The Charter of the French Language lays down detailed specifications regarding labour relations and business arrangements. These specifications create higher standards than the federal Official Languages Act and apply more broadly to private enterprise. Quebec’s linguistic jurisdiction in this regard was peremptorily refused by the Federal Trial Court in Association des gens de l’air v. Lang, but the Court’s conclusion was never confirmed on appeal.

Modern cooperative federalism and double aspect suggest that a province’s right to regulate civil rights could already regulate federal works and undertakings within its borders. The Supreme Court in Devine confirmed Quebec’s right to legislate on language; it further held in R v Beaulac that power to legislate on language rights was an ‘ancillary power’ to constitutional heads of power.

A stirring description of the Court’s finding in Beaulac occurred in 1899, when Lord Watson characterized the division between federal works and provincial regulation in terms amenable to cooperative federalism:

The British North America Act, whilst it gives the legislative control of the appellants’ railway quà railway to the Parliament of the Dominion, does not declare that the railway shall cease to be part of the provinces in which it is situated, or that it shall, in other respects, be exempted from the jurisdiction of the provincial legislatures.

This statement was applied in Ontario v Canadian Pacific Ltd, a 1995 case that questioned provincial regulation of environmental standards. Ontario’s environmental protection legislation regulated controlled burning; the railway was required to keep its lines free from combustible natural material. It disobeyed the provincial law while obeying the federal law, and the province charged the company with an environmental protection offense. The Supreme Court tersely applied Lord Watson’s statement to find that the province could regulate environmental standards for federal works.

The Supreme Court did decide in Bell Canada v Quebec that provincial governments could not control federal labour rights, which is a hurdle that language rights will need to clear. A Quebec-based employee relied on Quebec’s workplace protection regime instead of the federal regime. Bell contested this decision, and the Court found that provincial legislation couldn’t ‘bear on the specifically federal nature of the jurisdiction to which such works, things or persons are subject’.

The problem then becomes whether the language of work or business is sufficiently federal in nature to preclude provincial legislation. The Official Languages Act, for example, occupies the field for federal government and federal crown corporations: Quebec would not be able to enforce its language laws in this case. Federally chartered corporations, however, might not be able to escape so handily.

Another line of inquiry examines the degree to which regulation of language will frustrate a federal work’s federal purpose. This line of inquiry targets private enterprise controlled by federal laws, such as railways or banks.

My take on this problem is that language is a civil (rather than a human) right because it is so crucial to legal decisions. While a federal work might legitimately have a need to use a particular language (e.g., operators regulated by the Aeronautics Act, who have to use English in most radio communications), that need weighs against a province’s ability to legislate the language in which private decisions are officially conducted.

If language is characterized as a civil right, the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in Canadian Western Bank v Alberta supports the extension of Quebec’s Charter to federal works and undertakings. The case confirmed that banks, which are chartered under federal law, would have to submit to provincial legislation regulating insurance because it was an exercise of provincial power over civil rights. Justices Binnie and LeBel said that:

the courts must never lose sight of the fundamental rule of constitutional interpretation that, “[w]hen a federal statute can be properly interpreted so as not to interfere with a provincial statute, such an interpretation is to be applied in preference to another applicable construction which would bring about a conflict between the two statutes”.

If we apply this rule in the spirit of cooperative federalism, the application of Quebec’s Charter is already de jure.

If Parliament does not accede to Quebec’s request, a Court—I suggest the Federal Court—can interpret federal laws so as not to interfere with Quebec’s protection of the French language. In Lord Watson’s words, federal laws cannot cause federal works and undertakings to cease to be part of the provinces in which they are situated. The Supreme Court powerfully described language rights in Reference re. Manitoba Language Rights:

The importance of language rights is grounded in the essential role that language plays in human existence, development and dignity. It is through language that we are able to form concepts; to structure and order the world around us. Language bridges the gap between isolation and community, allowing humans to delineate the rights and duties they hold in respect of one another, and thus to live in society.

A more responsible Canadian federation admits unique provincial language concerns to a more universal application because of language’s particularly local nature. Provincial communities can only exist when united by language, and this is especially true for linguistic minorities, particularly so when they are an official language community.

Democracy Watch, an organization that works toward empowering Canadians and Canadian democracy, again turned to Federal Court to challenge the Canadian judicial appointments process. The organization’s frequent turns away from democratic institutions like Parliament speak to dwindling confidence in any sort of responsible government. The organization’s judicial challenge, in this case, speaks to the continuing colonial reality that is Canada’s parliamentary democracy.

The colonial reality to which I refer is a strong Crown—that is, a strong executive.

Canada’s parliamentary system has been influenced since its inception by foreign political concerns. As a British colony, Canadian parliaments and provincial legislatures were superintended by governors. Though our Queen is now Canadian, she is, and her predecessors were, British first, and the Governor-General remains a symbol of our colonial past.

Far be it for me to suggest a change to this arrangement: I don’t think a radical shift is necessary. I am concerned about the state of our parliaments when a problem with judicial appointments is not a subject of sustained parliamentary inquiry. The executive branch instead seems to have free reign to make appointments that cross into the overly political. I think that Democracy Watch is equally concerned with this point.

My concern redoubled when an academic asked to give some background on this piece flatly replied that ‘as order-in-council appointments, there’s very little role for Parliament to play.’ This statement is factually accurate. The governor’s council has always made these decisions without parliamentary involvement, but this fact misses the point. The Crown’s pick of judges might not be subject to parliamentary approval, but the judicial appointment process is subject to parliamentary oversight.

The application

Democracy Watch applied for judicial review against the federal judicial appointments process on November 5, 2020. The application alleges that the Attorney General of Canada considers candidates for appointment as superior court judges by referring to their political history, which creates a biased bench, thus undermining judicial impartiality.

There is truth to Democracy Watch’s claim. The Liberal Party of Canada maintains a database called Liberalist that it shares with the Prime Minister’s Office. The PMO uses the database, traditionally an election tool, when vetting judges. Liberal ministers, MPs, and other party officials have also been implicated in the vetting process. Democracy Watch’s court filing challenges these practises.

There is indeed cause for concern. The CBC today reported that a lawyer who contributed to the Attorney General’s nomination campaign was appointed to the Quebec Superior Court bench.

Odds of success

A court filing, however, doesn’t really strike at the heart of the matter. A political appointee can be an impartial judge because the legal system defines impartiality as ‘an absence of prejudice or bias, actual or perceived, on the part of a judge in a particular case.’ This narrow definition reflects judges’ roles as arbiters of particular facts, not general issues.

To be sure, impartiality has an institutional element. The Supreme Court recognized a test for institutional bias:

Step One: Having regard for a number of factors including, but not limited to, the nature of the occupation and the parties who appear before this type of judge, will there be a reasonable apprehension of bias in the mind of a fully informed person in a substantial number of cases?

Step Two: If the answer to that question is no, allegations of an apprehension of bias cannot be brought on an institutional level, but must be dealt with on a case-by-case basis. [Original emphasis]

Step one is the obvious issue raised by Democracy Watch in its filing, but it is unclear whether the government’s use of information regarding political contributions affects the appointee’s judicial decisions. Such an undertaking would require massive statistical analysis. Canadian superior courts rendered 620 944 civil judgments in the 2018-19 fiscal year. Combing through those cases to find patterns for a specific judge’s decisions is prohibitively expensive and time-consuming.

The breadth of cases suggests that Democracy Watch cannot establish a firm causal relationship between a political appointment and biased judgments. The legal system, moreover, presumes that judges are impartial unless there is proof to the contrary.

Democracy Watch has a tough row to hoe.

Enduring colonialist mentalities

Canada’s democratic development has historically proceeded through resistance to the colonizing Crown. The difficulties imposed upon governors-general by pre-Confederation legislatures forced them to accede to responsible government. That system of government confronted restive legislatures. Ministers had to convince their colleagues—even colleagues on their benches—that the executive’s will should be done.

As Canada became more independent through parliamentary resistance to royal control, the executive became naturalized and, thus, more capable of exercising control over Parliament. This move plays itself out in the historical consolidation of power in the Prime Minister’s Office. The colonial master, now largely forgotten, is replaced by an appointed official that bears the colonial royal imprimatur.

My charge of a continuing colonial reality in our parliamentary democracy is borne on parliamentarians’ reaction to this renewed centralization of power. They’ve done quite literally nothing. Commentators—journalists and pundits—point to the increasing politicization of legal disputes as a problem. This politicization is a problem, but it is caused by parliamentary inaction.

Analysis of Democracy Watch’s legal action is evidence of the problem. Wayne MacKay, a professor emeritus at Dalhousie’s Schulich School of Law told the Globe and Mail that Democracy Watch’s application is a political ploy to pressure government. The Law Times reported Mr. Wade Poziomka, Democracy Watch’s counsel, saying that the organization’s

first choice is to work with federal politicians and other stakeholders to achieve this goal. If litigation is necessary, however, Democracy Watch will argue the merits of its case before the Federal Court.

The court filing, coming as it does in a minority Parliament, seems meant to spur the opposition parties in the House of Commons to action. Democracy Watch has run campaigns to stop patronage appointments and unfair law enforcement. It is unclear, however, how Democracy Watch has engaged with these parties or with individual members regarding the subject of its present legal challenge.

What’s clear, though, is that parliamentarians in a system of responsible government like ours must hold the government to account. Members of Parliament and Senators, regardless of political persuasion, are delegated the responsibility of supervising the Crown and its ministers. This is a primordial duty, one that I have pointed up in other posts.

The point is trite but deadly serious: when confidence in Parliament fails, judicial challenges take on increasingly political colour. We shouldn’t bemoan these assays. Take them for the symptoms that they are and vote for MPs who can, regardless of party, have the presence of mind to criticize executive government when the government may be criticized. Speak also with senators, who are more independent than ever, to encourage them to poke and prod government.

Being an active subject means emulating the parliamentary example of Canada’s forebears. Tough judicial challenges only go so far. Concerted pressure for a more critical Parliament is the way.

The Nova Scotia House of Assembly has ground to a standstill for the nine months that COVID-19 has raged throughout the world. I contend that this legislative inaction can either be attributed to the hyper-politicization of parliamentary procedure or to uninformed members stumbling through the motions. Either case is concerning, and it should concern all Canadians: members of a House of Assembly are elected first and foremost to exercise their rights and responsibilities as legislators.

Nova Scotia’s gridlock reflects a cheapening of parliamentary representation because those we elect to legislatures are primarily tasked with specializing in vetting laws and government policy within the legislative context—with a knowledge of procedure. As MPs and members of assemblies move further away from this context, we lose true legislative representation.

The issue, in brief, is that the House of Assembly has not sat since March 10, 2020, and the government announced that it would end the current session on December 18. It is unusual for a Canadian legislature to not sit for nine months, although Nova Scotia’s rules only require two sittings a year. The opposition (composed of eighteen progressive conservatives, five NDP, and two independent members) has alleged that the government is blocking the legislature’s return, and major Canadian news outlets have reported the same problem.

These reports are inexact and compound the issue of members rights and responsibilities. Journalists connect the voting public with moves made in Canadian legislatures. Contextualizing these moves with due regard for the legislature’s traditions and rules is an essential element to keeping our representatives accountable.

Nuts and bolts

There’s a simple addition problem in the Nova Scotia legislature that makes the government reticent to meet the House of Assembly. The current Liberal government holds twenty-six seats out of fifty-one, but one of its members is the Speaker (and thus impartial). The Liberal government consequently holds an even half of the seats; the opposition also holds twenty-five seats. The government’s grasp on power depends on all of its members attending each sitting.

This situation resembles the BC legislature’s very close numbers after the forty-first general election in 2017. The governing Liberals there had forty-three seats, while the combined opposition parties held forty-four seats. The Liberal government met the House, lost a confidence vote, and the NDP opposition formed a government without an election.

In Nova Scotia’s case, of course, COVID-19 complicates sittings. A Liberal member could easily drop out of a vote or fail to attend if the legislature is authorized to sit remotely. If a couple of Liberal members drop out, the government could fall. There’s certainly political interest on the government side in not meeting the legislature.

Bear in mind that there’s political interest in the opposition not getting to grill the government in Province House. Allegations of undemocratic government are an easy narrative, one that might let an opposition party gain seats at an election, thus tipping the balance of power toward a new government.

The politicization of deadlock

The specter of a changed government or a general election looms for the governing Liberals in Nova Scotia. The opposition parties may or may not be ready for the hustings. The more critical problem is that they’ve abdicated all control over the legislative process and pin the problem on the government.

The NDP’s November 13, 2020, press release is a case-in-point. NDP House Leader Claudia Chender is quoted saying that:

The Liberals have consistently blocked Nova Scotians from asking questions through their elected representatives. They refused to meet through the pandemic, shut down committees for six months, and are once again shutting down the legislative processes meant to hold governments to account.

This statement over-simplifies the problem because governments do not control legislative sittings; members have this power. Governments only have the power to dissolve, prorogue, and summon legislatures.

The Progressive Conservative leader, Tim Houston, released a statement that pins the blame for no legislative debate on the government:

When the Legislature finally meets, it will be over 280 days since your elected MLAs last gathered at Province House. It will be open for less than an hour before it’s shut down again. By merely meeting this obligation, the McNeil Liberals are doing the bare minimum. Their continued culture of secrecy keeps them from answering to the people, for both their decisions and their indecision.

Rules

A look at the Assembly’s rules makes the issue clear. Rule 3(4) tells us that the House can’t sit without thirty days’ notice to members. This rule has been relied upon as the excuse for the House not sitting until prorogation, but the Speaker is able to recall the House at any time under rule 3(5):

wherever the House stands adjourned for a period of ten sitting days or more, if the Speaker is satisfied, after consultation with the Government, that the public interest requires that the House shall meet at an earlier time, the Speaker may give notice that being so satisfied the House shall meet.

Note the language here. The government is to be consulted, but the Speaker has the final say about when the House meets. The question for the Speaker in this circumstance is twofold. He is required to consider whether the public interest benefits from the House sitting. He is also required to consider the House’s best interest.

These are slightly different issues. The public interest is a broad, subjective concern. The House’s interest is defined by its members, whom the Speaker serves.

In the Westminster system, the Speaker defends all members’ rights, the most important of which is to speak in the House. Speaker John Allen Fraser, in the Canadian House of Commons, described this duty with reference to Speaker Lenthall, of the English House of Commons: ‘It was speaker Lenthall who, in the reign of Charles I, declared in the presence of the King that the Speaker’s first duty lay to the House of Commons.’ Speaker Fraser, moreover, described the application of parliamentary rules as a protection for the minority and majority: rules

‘are designed to allow the full expression of views on both sides of an issue. … This is the kind of balance essential to the procedure of a democratic assembly. Our rules were certainly never designed to permit the total frustration of one side or the other, the total stagnation of debate, or the total paralysis of the system.’

For these quotations, however, the system in Nova Scotia appears to have stalled.

When I speak with the opposition parties, they tell a story of frustrated procedure: the government will not agree to change the House’s procedure to allow electronic voting.

This response, and the opposition’s framing of the issue, is not convincing when the House of Assembly’s rules and the Speaker’s role are taken into account. The House in this case is evenly divided between government and opposition. Each side has twenty-five seats; neither side can claim to speak for the majority of members. In this context, either side could appeal to the Speaker to bring the House together, to hash out COVID-19 rules, and to debate issues of public interest.

I asked the Speaker whether he’d heard from members on this point. At the time of publication, the Speaker had not responded to my questions.

The bottom line

Members and the Speaker seem to be the crux of this debate. Their individual and collective inaction, perhaps caused by party politics, has deprived Nova Scotians of House of Assembly oversight. Commentary on this issue has, to date, been focused on the government’s actions. Much more careful attention needs to be paid to the opposition’s ability to bring the legislature together, and to the Speaker’s powers.

When these subjects receive their due, the story is unfortunately not so one-sided as politicians might like. With everyone to blame, voters have to consider whether the political culture that they’ve elected needs a kick-start to re-focus members’ attention on representing constituents. They can only really do so if the legislature sits.

Don your futurist caps and peer into a political reality in which technology accelerates the speed at which society changes; what role is left for conservatives? The political, deliberative realm that we sometimes trust to chart our societies’ course either fades as deliberative government becomes too lugubrious for rapid development, or the speed of deliberative government accelerates to a point where they might cease to exist. In either case, legislative thinking disappears, but these are the worst cases. A much more likely case is that deliberation continues unabated while power shifts from government to private corporate nodes.

Those who dominate current conservative discourse, a brand of neo-liberal, are largely adrift in any of these tech-fueled futures, and they represent the wider problems that assail government. The lack of adequate technological adaptation and regulation in public services is a symptom of governments’ slow movement. Conservatives who seek to preserve social norms even as society moves beyond them similarly fail to adapt and regulate, but this time because the message that they send is a moral or economic injunction.

‘Thou shalt not’, however, does not inspire, nor does it accomplish a worldly conservative agenda. That phrase writ large fixes on social preservation. Such an emotional response, engendered by clinging to past behaviour, has no place in a digital society where everything is liable to be impermanent unless consciously continued.

Bottom line: a longer view of conservative thought (theory) that unites ideas of conservation and pragmatic government is needed for a century that will experience dramatic technological change at breakneck speeds.

Conservation

At present, the increasing polarization of American and Western politics more generally grounds itself in facts: issues of the moment are assigned left-wing and right-wing descriptors ad hoc. Words like ‘liberal’, ‘conservative’, and ‘socialist’ are bandied about with regard to individual issues, and these descriptors stick based on patterns of behaviour. There is an inductive simplicity to this approach: Democrats are ‘liberal’ because they advocate solutions to issues that are generally more progressive; Republicans are ‘conservative’ because they believe in small government, so oppose democratic attempts to further regulate business, &c… Canadian politics, to take a second north-American example, has some similar divisions as social conservatism takes root in our Conservative Party.

Inductive reasoning, as I have elsewhere been at pains to illustrate, is faulty reasoning because it generalizes from particular cases that we might never see again. This reasoning has caused many to err in their appreciation for historical patterns and ways of living. These realities, though immensely valuable (again, I’ve touched on this elsewhere), are anachronisms from which we select concepts that ought to endure. This process is truly conservative because it implies curation.

Curation within the conservative tradition is magnificently expressed in Edmund Burke’s prose, prose which is sometimes associated with conservative movements. Burke frames a conservative intellectual stance as maintenance of continuity in social organization. His explanation of complex political systems relies on absolute self-interest that, in Lockean fashion, balanced competing self-interest: politicians and lawyers form their Plans upon what seems most eligible to their Imaginations, for the ordering of Mankind. I discover the Mistakes in those Plans, from the real known Consequences which have resulted from them. They have inlisted Reason to fight against itself, and employ its whole Force to prove that it is an insufficient Guide to them in the Conduct of their Lives. (A Vindication of Natural Society, 1756)

Emotion and reason, concepts that Burke plays on throughout his long rhetorical career, are juxtaposed in political systems. Emotion causes adherence to fantastic notions (perhaps those of bygone times); reason—Burke labels it as natural reason—is the tonic that can correct too much emotion. Reason can also, however, be used to create erroneous assumptions, ones that induce a bias. These inductive fantasies will successfully play to emotion, yet they provide little satisfaction for much of society because they do not serve the working population’s interest.

Induction aside, Burke acknowledges that tough love prevails: all organized societies are tyrannous because the will of others is imposed on individuals. There is violence in every society. Burke justifies the order because it is pragmatic. Some order is required to govern, even if the order is inevitably violent.

Burke’s later works explain the departure from or alteration of social order as a cultural phenomenon. In Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontents, Burke expresses the conservator’s fundamental truth: ‘Every age has its own manners and its politicks dependent upon them’ (1770). Understanding an idea’s context allows the able conservator to translate the idea into contemporary practice.

That practise receives extended treatment in Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France. This work against the French Revolutionary government encapsulates Burke’s late thinking on government: ‘to form a free government; that is, to temper together these opposite elements of liberty and restraint in one consistent work, requires much thought, deep reflection, a sagacious, powerful, and combining mind’ (1790). The quality of this mind proceeds from deductive reasoning. The form of government, once created, is sustained by pragmatic application of the principles of the form of government. The combining mind exerts itself with a view to the continuity of government, and the deep reflection required for this task is the curatorial instinct of a true conservative.

In brief, then, curation proceeds from a top-down logic that will control cases. The conservative in this view does not defend issues, but principles that have been selected to sustain government as a part of culture. The principles so selected inform the synonym of government and culture.

Preservation

Preservation—what I believe is the dominant misapprehension in conservative circles—fulfills Burke’s biting criticism of politicians in A Vindication of Natural Society. The tendency to hold something unchanged runs toward an ideal, a perfect image whose perfection is anachronistic. The image occupies the imaginer’s context without accounting for any historical concerns, so it is inherently flawed. Preservation fixes things out of context. Pure nostalgia animates this kind of view, but, without some mediating (and, ideally, dispassionate) intelligence, the emotion carries politicians and governed alike into stagnation.

Conservatives for a digital age

Conservatives will, on the above theory, flourish when they do the intellectual work of identifying the machinery of government and understanding whatever they wish to conserve as an artefact.

The faster pace of a digital world can and will admire these artefacts when they are contextualized because context shows social utility. That work of contextualization embraces a pragmatic view of politics and government, a view where propositions must be justified with reference to the machinery of government, history, and prospective value. This is a patient exercise, but one that can be achieved in a digital age if conservatives can build solid bases.

The populism that appears to overtake conservative movements reacts against a reasoned approach to government, thus defeating attempts at solid bases. Burke and many eighteenth-century politicos attribute populism to the breakdown of hierarchical authority. They are, in their way, correct. Technology’s decentralizing effect on governance structures, in terms of speed and distribution of power, presents fresh challenges that centralized political systems rarely face. Discovering fresh hierarchies, ones palatable to the governed, is an important challenge for conservatives and progressives alike. The conservative movement can’t hope to address these concerns without first having understood that conservation is not preservation.

President Donald Trump has petulantly refused to accept the results of the American 2020 presidential election. His campaign and the Republican Party have filed almost a dozen lawsuits in Nevada, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Georgia, with more on the way. His aggressive legal action—actions that are being described as ‘entirely without merit’ and ‘flailing’—will almost assuredly not affect the election’s outcome. They remain concerning because Trump’s moves are desperate and often appear to have no basis in fact. They are, in short, a textbook definition of vexatious litigation: frivolous lawsuits devoid of factual or legal merit. The suits are ‘politics disguised as a legal strategy’, as Kim Wehle points up in The Atlantic. A legal device, the bill of peace, has been specifically designed to deal with this kind of litigation.

Tackling lawsuits piecemeal takes time and energy, which are better spent preparing to govern or actually governing. Mr. Trump’s attacks target the President-elect’s victory, but the cost of defending state elections falls to individual states. The President is burning state cash, and he’s doing it while Congress hems and haws about a stimulus bill that could support state spending. The tactic sows discontent and further hampers states’ ability to respond to the pandemic.

A single, unified challenge to the election results seems to me like the best compromise. Fortunately, American law maintains a procedure that can force troublesome litigants into a single trial: the bill of peace. I explore the concept here and then show how it applies to Mr. Trump’s lawsuits.

The bill of peace

The bill of peace is an old device in Canadian and English jurisdictions; it is, however, current in the United States. The bill flows from an equity court’s injunctive power.

Bills of peace end judicial conflict by bringing all actions from all courts into a single superior court. They are akin to defensive class actions. That one court collects and tries all the related issues, settles them, and issues whatever orders it believes are necessary. An order can include a perpetual injunction that prevents a plaintiff from filing multiple actions on the same subject.

The bill originates, as far as I can tell, in eighteenth-century England. The House of Lords in Earl of Bath v Sherwin upheld a bill of peace granted after five separate trials rejected property claims made by the same plaintiffs against the same defendants. The lords in this case said that: ‘it was highly reasonable that a Court of Equity should interpose, and obviate the mischief by granting a perpetual injunction, after the right and only matter in question had been tried so often and fairly settled by so many solemn and concurring verdicts’. Translation: a bill of peace settles judicial conflict that can otherwise be brought again and again to keep the same issues alive in the courts.

In earlier American cases, for example, the bill was used in public law to restrain the state from collecting illegal taxes from a group of people. Courts in the 1890s even used the bill to stop the enforcement of state laws. The logic here was that the bill of peace resulted in an order that protected a wide swath the public or required a swath of the public to cease litigation against an individual.

American courts and legislatures have given us straightforward tests for the bill of peace. There is a general test for equitable relief, such as an injunction. The Michigan Court of Appeal cites the test in Nat’l Church Residences v. Porter: ‘Equitable relief is generally appropriate “when (1) justice requires it, (2) there is no adequate remedy at law, and (3) there exists a real and imminent danger of irreparable injury.”’ Georgia’s state code provides a specific test for granting a bill of peace at section 23-3-110:

(a) It being the interest of this state that there shall be an end of litigation, equity will entertain a bill of peace:

(1) To confirm some right which has been previously satisfactorily established by more than one legal trial and is likely to be litigated again;

(2) To avoid a multiplicity of actions by establishing a right, in favor of or against several persons, which is likely to be the subject of legal controversy; or

(3) In other similar cases.

(b) As ancillary to this jurisdiction, equity will grant perpetual injunctions.

The Michigan Court of Appeals in Hooker Chems & Plastics Corp. v A.G. recognized that a bill of peace ‘will lie after repeated trials at law and satisfactory verdicts to have an injunction against further litigation.’ The Federal Courts’ civil procedure rules also allow for bills of peace at Rule 23, which I quote as an appendix.

Application

These authorities give us some sense of the bill’s use; their application to Mr. Trump’s actual and threatened litigation is best understood with reference to Georgia’s rules. Mr. Trump has threatened litigation beginning on Monday in multiple states to contest the election results in those states. A Michigan court, a district federal court, and a Georgia court have already decided questions related to this issue. These facts beg for a bill of peace because Mr. Trump is litigating the same issues.

Mr. Trump’s legal challenges are attractive targets for a bill of peace because his tactics are transparent. USA Today documented his history of litigation across three decades. Mr. Trump has been involved in 4 095 cases, of which he initiated 2 121 as plaintiff. Litigation is expected from someone with Mr. Trump’s public profile. The New York Times and other media outlets have, however, noted up Trump’s litigation tactics. The President bullies companies, like lending banks, into a cost-benefit analysis by threatening and making good on litigation. This same tactic may be at work in Mr. Trump’s election litigation, although a simpler reason also exists: election litigation fundraising efforts are being used to fund litigation and pay off campaign expenses.

Michigan’s test for an injunction, which is laid down in Nat’l Church, buttons these facts up. The interest of justice in this case is a policy interest: the presidential election results should be confirmed as swiftly as possible. This sentence is normally a platitude; Mr. Trump has made confirmed results a national emergency by questioning electoral officials’ bona fides. He does so, however, for murky reasons. Are Trump campaign election challenges earnest efforts or efforts to cover debt? The election cases to date and Mr. Trump’s litigation history don’t give a clear answer.

Law has a tough time responding in a systematic way to sweeping litigation across state lines on minuscule electoral improprieties under-girded by an unproven belief that elections fraud occurred. Legislation and common law allow suits to be filed whenever a right is allegedly infringed. Mr. Trump alleges, and the courts begin moving. One remedy for multiple trials on the same or similar issues is a bill of peace. Its origin in equity cuts through the legal machine by forcing one trial of all the issues. An injunction to this effect is an efficient vehicle that short-circuits prolonged litigation.

The immanent danger of destabilizing the presidential election’s results, possibly fomenting violence, and doing these things during a pandemic all point to irreparable harm on a national scale.

Wrapping up

Mr. Trump’s present suits will have to be examined one-by-one to determine whether each fits the criteria for frivolity, which would indicate a vexatious pattern that could be resolved with a bill of peace.

The public information about these suits does suggest that Mr. Trump’s lawyers are carpet bombing to find irregularities by judicial fiat. A court can order reams of evidence to settle a case. This level of scrutiny is bound to uncover some errors, and a demagogue like Mr. Trump might magnify these trifles to threaten the election’s legitimacy.

The above is not, of course, an exhaustive review of this subject. It does, however, point to some means of short-circuiting Mr. Trump’s strategy. To be clear, that strategy has not as yet yielded substantial fruit. If Mr. Trump were able to bring a meaningful case before the courts, he deserves his day. A bill of peace would still give him this chance to plead his legal case. It simply brings all the questions before a single court. Which court is a post for another day, or, perhaps, for a licensed American attorney.

Further Reading

- Allstate Ins. Co. v. Hill, 1962 Ga LEXIS 522 (Supreme Court of Georgia 1962).

- Bath (Earl of) v Sherwin, 4 Bro. P.C. 373 (UK HL 1709).

- Bray, Samuel L. ‘Multiple Chancellors: Reforming the National Injunction’. Harvard Law Review 131, no. December (2017): 418.

- Dykun v. Odishaw, 2001 ABCA 204 (n.d.).

- Hooker Chems. & Plastic Corp. v. AG, 100 Mich. App. 203 (Court of Appeals of Michigan 1980).

- McManamon, Mary Brigid. ‘Felix Frankfurter: The Architect of “Our Federalism”’. Georgia Law Review 27, no. Spring (1993): 697.

- Moreton Rolleston, Jr., Living Trust v. Kennedy, 2004 Ga LEXIS 16 (Supreme Court of Georgia 2004).

- Nat’l Church Residences v. Porter, 2017 Mich. App LEXIS 1007 (Court of Appeals of Michigan 2017).

- Official Code of Georgia (n.d.).

- Rodgers v. Bryant, 2019 U.S. App. LEXCIS 33173 (United States Court of Appeals for the Eight Circuit 2019).

- Sohoni, Mila. ‘The Lost History of the “Universal” Injunction’. Harvard Law Review 133, no. January (2020): 920.

- USCS Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 23

The rule creates the power to issue a bill of peace

(a) Prerequisites. One or more members of a class may sue or be sued as representative parties on behalf of all members only if:

(1) the class is so numerous that joinder of all members is impracticable;

(2) there are questions of law or fact common to the class;

(3) the claims or defenses of the representative parties are typical of the claims or defenses of the class; and

(4) the representative parties will fairly and adequately protect the interests of the class.

(b) Types of Class Actions. A class action may be maintained if Rule 23(a) is satisfied and if:

…

(3) the court finds that the questions of law or fact common to class members predominate over any questions affecting only individual members, and that a class action is superior to other available methods for fairly and efficiently adjudicating the controversy. The matters pertinent to these findings include:

(A) the class members’ interests in individually controlling the prosecution or defense of separate actions;

(B) the extent and nature of any litigation concerning the controversy already begun by or against class members;

(C) the desirability or undesirability of concentrating the litigation of the claims in the particular forum; and

(D) the likely difficulties in managing a class action.

David Hume’s is-ought problem is oft-forgotten in Canadian political and legal circles, and it bears some repetition. We often forget the value of deduction in an algorithmic age, for computers and the science from which they stem cause us to increasingly rely on inductive logic. In this age of induction, we formulate general rules based on observations when those observations admit to much more limited claims that, taken together, might build a general rule.

These different approaches have characterized debates between sciences and humanities since Plato and Aristotle. David Hume’s contribution extends beyond his is-ought principle, but this principle does bring the immediate problem in political science and law into focus:

Morality is a subject that interests us above all others: We fancy the peace of society to be at stake in every decision concerning it; and ’tis evident, that this concern must make our speculations appear more real and solid, than where the subject is, in a great measure, indifferent to us. What affects us, we conclude can never be a chimera; and as our passion is engag’d on the one side or the other, we naturally think that the question lies within human comprehension; which, in other cases of this nature, we are apt to entertain some doubt of.

A Treatise of Human Nature, 3.1.1.1

Hume does not directly touch upon the dichotomy I’ve expressed. Induction and deduction are not mentioned in this passage; they underlie the debate. Hume takes aim at morality deployed in argument. Prescriptions for the good life are erroneously ascribed inductive weight, which skews arguments toward what a subject thinks ought to be. Similarly, the invocation of a status quo becomes sufficient argument for a desirable state of affairs.

Hence that opening appositive: ‘We fancy the peace of society to be at stake in every decision concerning it’. An apposite example is some political scientists’ desire to limit the Crown’s ability to prorogue Parliament (see ‘Constitutional Peace, Political Order, or Good Government? Organizing Scholarly Views on the 2008 Prorogation’, p. 114; ‘(Mis)Representing the 2008 Prorogation: Agendas, Frames, and Debates in Canada’s Mediacracy’). This prescription for the good life—or, better stated, the popular-democratic life—is a fantasy borne from induction. It makes a claim for what ought to be, yet some political scientists and administrative lawyers will claim that our polity is threatened by prorogation when Parliament is noticeably at odds with cabinet. The so-called prorogation crisis in 2008 took on existential significance because academics and lawyers billed the Crown’s possible intercession as a crisis. They imposed their own view of the right society—be it increased responsible government, increased cabinet proceduralism, etc.—to argue for and against prorogation, which was itself a political issue.

Courts have historically refused to intercede in these affairs because they rightly identify (though they rarely discuss) the is-ought principle at work. Politicians have the latitude to make empty promises and sweeping proclamations. Judges are technicians whose province is, in common law at least, the application of legal rules through deductive means (see Operation Dismantle, para. 52, restated in Hupacasath, para. 66). The ‘subject matter’ is, to refer to our quotation, ‘indifferent’ to a judge. What ought to be done does not enter a common lawyer’s mind. The law is applied, and even equity follows the law. The application of rules to fact often proceeds without regard for broader policy or moral questions.

Charter litigation does, to be sure, change the game somewhat. These general rules are imposed by universal legislation on every aspect of Canadian law and politics. The Charter‘s prescriptions are a form of moral induction that allows academics, lawyers, and litigants to channel their passion into a cause of application for ‘one side or the other’. Courts have restrained such passion by imposing fairly strict legal tests on every cause of action. The government, moreover, always has an advantage in its promoting a ‘free and democratic society’.

The limiting tests build a deductive framework into Charter litigation, and it is the frustrating deduction of a particular worldview. I cannot enter into this subject in the depth required to do it justice. Suffice, for the present, to say that the judicial perspectives that have shaped Charter jurisprudence have represented a very normative and centralizing view of what may and may not be tolerated in a ‘free and democratic society’. The resulting deductions have constrained minorities even as the majority has adopted the Charter as something of a ‘passion’. Hume’s worry about morality is that the passion we feel when our colours are up on an issue gives us a false certainty. What ought to be becomes a statement of fact: ‘we naturally think that the question lies within human comprehension’. Hubris obtains, and Hume explains such arrogance in his Problem of Induction:

Shou’d it be said, that we have experience, that the same power continues united with the same object, and that like objects are endow’d with like powers, I wou’d renew my question, Why from this experience we form any conclusion beyond those past instances, of which we have had experience? If you answer this question in the same manner as the preceding, your answer gives still occasion to a new question of the same kind, even in infinitum; which clearly proves, that the foregoing reasoning had no just foundation.

A Treatise of Human Nature, 1.3.6.10

The problem with induction is that inductive reasoning’s premises become self-referential. The observed occurrence must be true all the time for the proven rule to obtain. The experience on which we attempt to theorize a general rule is not broad enough to determine the general rule, and this problem repeats itself throughout the reasoning. Its premises cannot lead to a logical conclusion, but it is tempting to place our faith in this conclusion when our experience and our emotions inspire worldviews or strong opinions.

A.V. Dicey, for his many faults, valued the deductive principles that animate common law. He holds in one part of the Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution that ‘there runs through the English constitution that inseparable connection between the means of enforcing a right and the right to be enforced which is the strength of judicial legislation’ (p. 186). The practical nature of judge-made law builds upon the facts of each case. Dicey again valorizes deductive reasoning when he puns on the word:

So far, therefore, from its being true that the sovereignty of Parliament is deduction from abstract theories of jurisprudence, a critic would come nearer the truth who asserted that [John] Austin’s theory of sovereignty is suggested by the position of the English Parliament.

p. 68

Dicey means to dispute John Austin’s theory of sovereignty while making clear that the dispute relies on his and Austin’s observations of the English Parliament. Both writers are working to deduce a truth based, as Hume might say, on impressions left by the institution of Parliament.

An example adjacent to prorogation evokes Hume’s problem alongside the is-ought principle even as it seeks to reject some of Dicey’s views. Leonid Sirota (author of Double Aspect) has recently published a piece, ‘Immuring Dicey’s Ghost: the Senate Reform Reference and Constitutional Conventions’, in the Ottawa Law Review in which he argues that Canadian constitutional conventions have or can be turned into law by an activist Supreme Court (p. 318). He treats the Supreme Court’s decision in the recent Senate Reference as a convincing precedent for granting constitutional conventions force of law. A telling paragraph from his conclusion summarizes the argument:

Contrary to what some scholars have suggested, [the Court’s decision that the Senate could not be made elected by simple legislation] does not mean that the Court was oblivious to the existence of conventions regulating the Senate’s place in the constitutional framework, let alone hostile to the very notion of conventions. Rather, conventions are the principal component of the “constitutional architecture” that the Supreme Court invokes, but only defines as consisting of assumptions underlying the constitutional text. The text—first the Constitution Act, 1867, and then the amending formulae included in the Constitution Act, 1982—has been written with conventions, including those governing the Senate, in mind. The Supreme Court’s opinion recognizes this but does not say so.

p. 359

Sirota focuses on the Court’s use of ‘architecture’ in the Senate Reference and in two previous references, the Secession Reference and the Supreme Court Act Reference, without properly evoking the word’s use and meaning. He uses induction to appeal to scholars who share his view. The final sentence in the above-quoted paragraph bears this reading out. Sirota may be reading an opinion into the Court’s use of ‘architecture’: the Court’s recognition of conventions as law depends on a ‘metaphor’ (p. 320). The metaphor later receives treatment as a ‘concept’ (p. 327), which appellation subtly turns the illustrative figure of speech into ‘a general idea or notion, a universal; a mental representation of the essential or typical properties of something’ (OED). This change is disingenuous because it casts an image of the constitution as an idea about the constitution. This elision is more fully pronounced: ‘Under the Canadian Constitution [sic], conventions are sometimes essential evidence of the acceptance of fundamental principles’ (p. 438, emphasis original). Conventions become evidence of a metaphor that has been turned into an idea suitable for use in constitutional interpretation. Sirota’s induction imposes his argument on the word instead of showing the word’s ability to move past metaphor.

Sirota’s inductive account is confirmed when he proclaims that

whatever label one might use, the real issue is whether the Court incorporated constitutional rules that were previously regarded as matters of politics alone into law. As I have argued above, it did just that, and this is significant.

p. 335

Sirota argues here that there has been historical shift in judicial appreciation of convention, yet he fails to show how the Supreme Court demonstrated its acknowledgment of conventions as law: ‘the Supreme court is well aware that “conventional constitutionalism” was always meant to supply the regulations that the Fathers of Confederation knowingly left unstated in the constitutional text’ (p. 334). The Court’s careful avoidance of convention is read as acknowledgment of conventions’ normative, thus legal, value. The absence of evidence has become the evidence of a norm: Sirota concludes that the Court’s mention of ‘constitutional architecture’ allows him to show that the Court has allowed itself to enforce certain conventions.

A further elision of terms is suggestive of induction: Sirota holds that certain conventions are constitutionally entrenched ‘and thus enforceable, if only against attempts to amend the Constitution’ (p. 339. sic). This sentence contains a category shift: bars to amending the constitution do not allow the courts to enforce constitutional convention. Judicial enforcement occurs when a legal right is negated. Amendment purports to alter a legal right. Constitutional conventions in this system ‘carry only political sanctions’ (Reference re Secession of Quebec, para. 98). Those sanctions are under-explored in Sirota’s piece, but they may (as I have elsewhere suggested) be considered Parliament’s inherent jurisdiction, thus depriving courts of any power to enforce convention. Sirota’s category shift refers to his identification of the real issue in the Court’s Senate Reference decision: if the Court incorporates a political rule into legal treatment, that rule becomes law; if the Supreme Court notices a political rule to bar constitutional amendment, the noticed rule is a legal rule. This premise sustains Sirota’s argument because it is repeated in different form.

This objective assessment of Sirota’s piece incorporates Hume’s Problem of Induction; the is-ought principle digs into Sirota’s motives for writing. Those motives are only properly known to him. The is-ought problem can only be used to caution scholars writing on constitutional conventions or the royal prerogatives: the inductive fantasy leads you astray when you ‘fancy the peace of society to be at stake’ and write to correct the situation. Canadian law will change when scholars identify remedies and show courts how these solutions work alongside other cases in which the same rights were asserted. In so hewing to recorded experience, counsel and academics better demonstrate how the solution is supported by ‘human comprehension’. If common law may stand for one progressive thing, let it be that our collective previous experience may be used to advance judicial remedies.

I find it irksome that Canadian lawyers often resort to the law courts without any regard – at most very little regard – for the ancient role of the legislator as a court of grievances. This phenomenon is especially important in a time when Canada’s Charter of Rights is often pled to establish a new frame of reference for social issues of the day.

Most people trained in law will rebel at the suggestion that Parliament could ever be a court. Conflating the legislature with judicial office undermines the division of powers that defines our Americanized view of government.1

An historically accurate assessment of our parliamentary democracy ignores such divisions. One compelling example is the early Northwest territories. The Act to amend and consolidate the Laws respecting the North-West Territories stipulated that stipendiary magistrates sit ex-officio on the Lieutenant-Governor’s council, which was charged with the creation of laws and administration of government.2

This reality has, of course, shifted over time: we no longer speak of assemblies as courts with judicial functions. Casting back, however, to our feudal roots in England shows that Parliament was conceived as a court for grievances that could be put up against common law courts’ powers. The critical feudal division of power lies in the spheres of advise that individuals or groups are privileged to offer the Sovereign, for which concomitant privileges are attached. I will describe this phenomenon and then apply it to Charter litigation in Canada.

The origin of Parliament

Frederic W. Maitland ascribes the origin of Parliament, albeit indirectly, to Magna Carta. King John’s 1215 charter submits the Crown to the ‘common counsel of our realm’ when raising most classes of funds.3 Even before this time, in 1213, Maitland has John summoning a council at Oxford composed of ‘four lawful men of every shire, ad loquendum nobiscum de negotiis regni nostri‘.4 These discussions allowed the Crown legitimacy, and John’s failure to adequately consult eventually contributed to the eruption of conflict with his barons.