This note is the first of two that outline the interplay between air operators’ passenger tariffs and Transport Canada’s requirement to remove unruly or unsafe passengers from aircraft. The notes are inspired by Zoghbi v. Air Canada, a case in which the Montreal Convention was put up to preclude a human rights claim for invoking Transport Canada’s requirement. The regulation regarding unruly passengers, though broad, subjects operators to heightened administrative and judicial scrutiny for human rights abuses. Operators’ private regulations are subject to ministerial scrutiny, thus making them impeachable beyond simple damages, which may be precluded by the Montreal Convention.

The notes together suggest a broader approach for Zoghbi and similar cases in which human rights issues arise in connection with passenger air transport before Canadian tribunals and courts. Mr. Zoghbi raised a constitutional challenge to the Convention’s seemingly broad application: it prevents claims for damages arising under human rights legislation, thus (so he argued) violating section 15 of the Charter. The Court did not deal with this challenge; and the challenge is an ultimate effort. This note sketches out another argument that relies on the Convention’s text to open airlines to the full range of claims under the Canadian Human Rights Act.

Where a man has but one remedy to come at his right, if he loses that he loses his right.

Lord Holt, Ashby v White [1703] 2 Ld. Raym. 938, p. 954.

This note discusses preclusion of actions under the Montreal Convention. A close reading of the Convention shows that intentionally negligent or reckless acts by airline staff are not protected by the Convention. This reading is no artful pleading: this international agreement limits itself to protecting airlines from overwhelming costs in the wake of an accident. Its objective does not include insulating airlines from civil liability in all circumstances. Airline employees who abuse their positions of authority–which is the subject of the second note in this series–are open to suits under the Convention.

The case

Zoghbi v. Air Canada is a continuing case remitted by the Federal Court to the Canadian Human Rights Commission. The decision reported at 2021 FC 1154 deals with the threshold issue of the Montreal Convention’s application. The Court ruled that the Montreal Convention did not preclude the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal’s jurisdiction, which goes beyond a simple award of damages. Justice Fothergill limited his analysis to the judicial review before him. He rightly noted that the Montreal Convention does not obviously preclude a human rights claim against an operator. The substantive issue, the human rights claim against Air Canada, remains pending the Commission’s decision.

Mr. Zoghbi was removed from an aircraft on the ramp at Halifax airport after he asked to speak to a manager about a flight attendant’s conduct. Air Canada subsequently banned him from flying with the carrier because an employee reported him as having been verbally abusive toward staff. Mr. Zoghbi filed a complaint of discrimination on the basis of race, national or ethnic origin, colour, and/or religion with the Canadian Human Rights Commission.

The complaint never got off the ground because the Commission dismissed Mr. Zoghbi’s case as ‘trivial’. The Commission found that the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal could not make a financial award nor could it order Air Canada to apologize for its employees’ conduct. The Montreal Convention, which is implemented by schedule 6 of the Carriage by Air Act, precluded Air Canada from liability other than the value of Mr. Zoghbi’s ticket. The Federal Court reversed the Commission’s conclusion:

The Commission assumed that the possible unavailability of financial compensation for breaches of human rights in the context of international air travel was a bar to all meaningful remedies. The Commission failed to consider whether other remedies, such as measures to redress the alleged discriminatory practice or prevent similar practices from occurring in future, might be appropriate. Its decision to dismiss Mr. Zoghbi’s complaint as trivial was therefore unreasonable. (Para. 52)

The matter now goes back to the Commission, and Mr. Zoghbi has raised a constitutional question regarding the Montreal Convention’s bar to awards of human rights damages. Justice Fothergill declined to rule on this question because the issue had not been sufficiently argued, nor had it accounted for evidence.

The problem with the Montreal Convention

The constitutional question that Mr. Zoghbi raised before the Federal Court questions the Montreal Convention’s very wide net, which has been characterized as an ‘entire liability scheme’.[1] That scheme is detailed in articles 29 and 17 of the Convention; it only applies to damages that arise out of an accident. That wisdom may be disputed without reference to the Charter. The Convention may not apply to intentional discrimination by airline employees: an act designed to discriminate is reckless in Canadian law. The Convention, as Justice Fothergill points up, does not prohibit non-pecuniary remedies.

The typical argument that shields an airline from liability frames the Convention as an international order designed to ensure uniformity of liability.[2] Articles 29[3] and 17[4] combine to preclude ‘any action for damages, however founded’ from being brought when ‘the accident which caused the death or injury took place on board the aircraft or in the course of any of the operations of embarking or disembarking’. These provisions do not explicitly cover human rights claims (Zoghbi, para. 52), nor do they necessarily cover claims not related to an accident.[5]

Limiting human rights abuses at Canadian law

The Montreal Convention and its predecessor treaty use sweeping language that courts rarely disturb. Courts and administrative tribunals may be able to limiting the worst abuses by distinguishing between normal conduct in the course of an airline’s business and conduct that takes an employee outside of her or his regular employment. A claim for damages can result against an airline’s employees if they intentionally harm a passenger or are intentionally negligent. This rule arises through article 30 of the Convention. Article 30 finds application because human rights abuses break into two categories: intentional and unintentional discrimination.[6] The Canadian Human Rights Act stipulates additional penalties for willful or reckless discrimination,[7] thus harmonizing with article 30 of the Convention.[8]

Paragraphs one and two of article 30[9] extend the Convention’s limits to damages caused by airline employees in the course of their duties.[10] Paragraph 3,[11] however, opens airline employees to liability if they behave recklessly with knowledge that damage would likely result. The scant commentary on this section snubs the Convention’s application to airline employees or agents:

These provisions extend the protection afforded to the carrier to servants and agents, which may not be substantial enough to be ‘‘worth powder and shot’’ by claimants. To allow claimants to recover from agents what the regime does not allow them to recover from carriers would subvert the regime.

Contracts of Carriage by Air

The practical analysis of potential claims against airline employees adds little to the argument that employees cannot be responsible under the Convention. Recovery may be limited, but the treaty’s text is clear enough that the regime does not apply to employees who intend to cause damage or who behave recklessly. If the regime does not apply, any damage may be claimed against an employee (thus circumventing the need to find bodily harm under article 17).[12]

Conduct that makes an employee liable must be a combination of intent to damage or recklessness and knowing that damage will result.[13] An airline employee becomes liable to the exclusion of her or his employer when a plaintiff proves mens rea.[14] That high bar has not been considered in relation to the Montreal Convention; the Warsaw Convention’s language is similar enough to ground interpretations of the intention required, or the recklessness needed, to open an employee to liability.

An intent to harm is straightforward, for the mens rea required to prove intent must be based on unequivocal evidence. That evidence is unlikely to obtain in a safety sensitive culture like aviation’s.

Recklessness requires a negligent attitude that disregards a very real potential for harm. The English Court of Appeal defined the term in Goldman v Thai Airways International Ltd.:

When conduct is stigmatised as reckless, it is because it engenders the risk of undesirable consequences. When a person acts recklessly he acts in a manner which indicates a decision to run the risk or a mental attitude of indifference to its existence.

[1983] 3 All ER 693, p. 699.

Stigma and risk are the foci of this definition. Conduct that is stigmatized is not simply forbidden: such conduct is openly denounced. It is possessed of infamy. The risk associated with such conduct is in part the reason for stigmatization, so the two run together in the Court’s definition. Ignoring or being ignorant of the stigma rises to the level of reckless conduct. Such ignorance–apparently in conflict with the meaning of stigma–was to be appreciated by the Court in terms of the employee’s or airline’s knowledge during the incident.[15] American courts, however, blend the standards while observing that a fact finder may infer that the risk of harm was so obvious that the defendant could not have but known of the risk.[16]

The Canadian Human Rights Act prohibits discrimination because the conduct, at this point in Liberal rhetoric, is stigmatized. Whether a miserly employee agrees with those prohibitions, it beggars belief that even such an employee would not be aware of the stigma. The prohibition bleeds through a subjective standard that assesses an employee’s awareness of the prohibition and the risk of harm during the incident. Those harms are weekly featured in media; their effects receive academic and popular attention.

Each case, of course, requires special focus on an employee’s intent, which invokes the distinction between direct and indirect, intentional or unwitting, discrimination. Under the Montreal Convention, unwitting discrimination likely doesn’t rise to a level that engages article 30, paragraph 3, of the Convention. An employee’s unintentional discrimination falls under the Convention’s protection because the employee’s mistake occurred in the course of her or his employment. Only intentional discrimination fits the Convetion’s exception. These cases are likely handled through administrative processes, which may include those established by the Canadian Human Rights Act.[17]

Law does not present a clear solution

Canadian law is one system in which domestic human rights commitments conflict with the Montreal Convention. Judges give such weight to the Convention that, though it is incorporated in Canadian law (and thus putatively on a level field with the Canadian Human Rights Act), Canada’s judge-made law doesn’t seem like a useful forum. The Convention’s application is a political matter suited for parliamentary debate and executive intervention.

Zoghbi brings this tension between the Montreal Convention and Canadian human rights law into view. At the beginning of a century in which air (and space) travel will continue to proliferate, this cleavage merits legal and political scrutiny. Insulating airlines from all claims is efficient; it flies in the face of national and international commitments into which Canada and many other states affiliated with the International Civil Aviation Organization have entered.

Notes

[1] Malcolm A. Clarke, Contracts of Carriage by Air, 2nd ed., (London: Lloyd’s List, 2010), p. 161.

[2] Thibodeau v. Air Canada, 2014 SCC 67, paras. 14, 75.

[3] 29. In the carriage of passengers, baggage and cargo, any action for damages, however founded, whether under this Convention or in contract or in tort or otherwise, can only be brought subject to the conditions and such limits of liability as are set out in this Convention without prejudice to the question as to who are the persons who have the right to bring suit and what are their respective rights. In any such action, punitive, exemplary or any other non-compensatory damages shall not be recoverable.

[4] 17.1. The carrier is liable for damage sustained in case of death or bodily injury of a passenger upon condition only that the accident which caused the death or injury took place on board the aircraft or in the course of any of the operations of embarking or disembarking.

[5] See the US Second Circuit Court of Appeals decision in Tsui Yuan Tseng v. El Al Israel Airlines, Ltd., 122 F.3d 99 (2d Cir. 1997), pp. 104-5, but reversed in El Al Israel Airlines, Ltd. v. Tsui Yuan Tseng, 119 S. Ct. 662 (1999), p. 176.

[6] See McGill University Health Centre (Montreal General Hospital) v. Syndicat des employés de l’Hôpital général de Montréal, 2007 SCC 4, para. 48, where the Supreme Court condensed the definition of discrimination: ‘The essence of discrimination is in the arbitrariness of its negative impact, that is, the arbitrariness of the barriers imposed, whether intentionally or unwittingly.’

[7] RSC 1985, c H-6, s. 53(3): In addition to any order under subsection (2), the member or panel may order the person to pay such compensation not exceeding twenty thousand dollars to the victim as the member or panel may determine if the member or panel finds that the person is engaging or has engaged in the discriminatory practice wilfully or recklessly.

[8] Butler v Aeromexico, [1985] 774 F2d 429: In the case at bar the District Court’s primary reliance was upon the judicial interpretation of the Convention’s primary term “wilful misconduct,” but as a second string to its bow was pointing out that if it were needful to resort to local law, the Alabama concept of “wantonness” was substantially equivalent to the Convention’s primary standard and would support the decision reached by the court. We see no harm to appellant or harmful error (if there be any discrepancy at all in the international standard and the Alabama standard) in the District Court’s discussion of this comparison.

[9] 1. If an action is brought against a servant or agent of the carrier arising out of damage to which the Convention relates, such servant or agent, if they prove that they acted within the scope of their employment, shall be entitled to avail themselves of the conditions and limits of liability which the carrier itself is entitled to invoke under this Convention.

2. The aggregate of the amounts recoverable from the carrier, its servants and agents, in that case, shall not exceed the said limits.

[10] A point made with little analysis in Walton v MyTravel Canada Holdings Inc., 2006 SKQB 231, at para. 32.

[11] 30.3. Save in respect of the carriage of cargo, the provisions of paragraphs 1 and 2 of this Article shall not apply if it is proved that the damage resulted from an act or omission of the servant or agent done with intent to cause damage or recklessly and with knowledge that damage would probably result.

[12] Note that the predecessor to the Montreal Convention (the Warsaw Convention of 1929) contained a provision that made carrier liable for acts or omissions borne from an intent to harm or from recklessness (art. 25: The limits of liability specified in Article 22 shall not apply if it is proved that the damage resulted from an act or omission of the carrier, his servants or agents, done with intent to cause damage or recklessly and with knowledge that damage would probably result; provided that, in the case of such act or omission of a servant or agent, it is also proved that he was acting within the scope of his employment). This provision no longer exists; only employees can be held liable–an iniquitous system in which corporations are safe from suit, yet employees are exposed to attack.

[13] International limitation of liability exists for maritime transportation, which is an older field than aviation. The terms in this field are better-defined and shed light on the Montreal Convention’s language. See: Norman A Martínez Gutiérrez, Limitation of Liability for Maritime Claims, in The IMLI Manual on International Maritime Law, ed. David Joseph Attard and Malgosia Fitzmaurice, 1st ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 551-75, pp. 564-5.

[14] Sub-section 126(1) of the Criminal Code of Canada requires a similarly high mens rea: ‘every person who, without lawful excuse, contravenes an Act of Parliament by intentionally doing anything that it forbids or by intentionally omitting to do anything that it requires to be done is, unless a punishment is expressly provided by law,’ guilty of an offense.

[15] Ibidem, p. 703. Vide. Nugent v Michael Goss Aviation Ltd, [2000] All ER (D) 549, 2 Lloyd s Rep 222. American courts take a markedly different view that conforms to an objective analysis of a person’s knowledge: In re Air Crash Near Cali, Colombia on December 20, 1995, [1997] 985 F Supp 1106, pp. 1124-9. See in particular p. 1129: ‘Construing “reckless disregard” as tantamount to objective recklessness also makes sound practical and policy sense. If an airline’s employees are exposed to a plain, palpable and certain danger, and nevertheless intentionally perform acts that deviate substantially from the acknowledged standard of care, the absence of proof that they subjectively recognized the harm that likely would result from their conduct does not make them a great deal less culpable.’

[16] Piamba Cortes v American Airlines, Inc, [1999] 177 F3d 1272, p. 1291.

[17] Section 113.1 of the Air Transportation Regulations (SOR/88-58), when read alongside section 111 of those regulations, appears to provide a more effective means of relief for passengers affected by a breach of their human rights. The Canadian Transportation Agency is, however, not specialized in human rights law. A remedy under these regulations may not adequately respond to the human rights issues raised on the facts of a case. The Agency, however, may be a useful forum for complaints of unintentional discrimination.

Business research is often viewed as a wish-list item. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Business research is akin to performing preventive maintenance on a car while inventing new technology for the vehicle. It can save a business’ bacon and increase its productivity.

There is little talk about business research as an organized activity. Corporate research gets some attention, but business research falls flat. The difference is one of scale. Corporations that fund research departments often have considerable resources at their disposal. Smaller firms have it or they don’t; attend a librarians’ conference if you’d like to hear more. Some companies specialize in market research; other, larger companies, provide global solutions. These divisions are suitable for a bygone era, where divisions of labour were relatively clear and large businesses abounded. The expanding gig economy and an increasing presence of digital disruptors means that less clear divisions exist. This fog of war gives smaller, more dynamic firms the ability to gain ground.

‘Business research’ in this context means more than corporate or market research. It embraces the strategic and tactical dimensions of corporate and market research while also fulfilling the gig economy’s need for client-focused, local research. That is to say, business research embraces an enterprise’s front and back ends to deliver seamless service. It is an essential part of the gig economy and Industry 4.0, for the gig economy’s main means of exchange is through the information super-highway. Business research processes digital and analog information to create or encode most every product that we possess.

This changing landscape affords a fresh understanding of business research suited to gig workers and disruptors. All that’s needed is a glance at a humble librarian’s career at the end of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, where the changes to research and knowledge management revolutionized the librarian’s and the researcher’s roles…only to maintain the cardinal principle that makes business research worthwhile.

My father was a librarian who spent his career organizing and tending to corporate knowledge. He mainly worked in big firms providing corporate and market research. The libraries in which he worked were designed to support profit centers.

I remember spending my childhood in those libraries, and my formative years were traditional libraries’ last kick at the can. I’d go to work with my dad and spend time antagonizing (in retrospect) very kind librarians. My love of books no doubt sprung from these interactions.

As we delve into the twenty-first century, however, physical libraries become less relevant. I saw this firsthand with my pops, whose role began to emphasize finding information over organizing it. These roles, of course, go hand in hand. Information is only found by those who understand it’s organization.

The scale on which electronic, networked, organization is conducted changed the game. The information with which my father dealt in the last year’s of his career was more mercurial than ever. Large data sets and the availability of qualitative sources made it relatively easy to know something without understanding anything. The large firms at which my dad worked were able to move past this barrier to entry. They employed analysts and librarians to interpret massive databases.

Therein lies the problem. The work of interpreting such databases is increasingly being completed by machines that are inherently quantitative mechanisms. Large companies’ economies of scale continue to scale, and librarians like my father find themselves redundant in a new world that sometimes forgets the importance of human research.

The career that my father wound up traced the great lines of this forgetting–and Ray Bradbury would be proud of the results. It’s now difficult to track news in a deluge of information, let alone discrete research tasks. Why not let a computer do the heavy lifting? Librarians are costly investments and the results of their efforts are fallible. Work to the bottom line.

My old man’s career cut through the process of forgetting. He walked out of a master’s degree in library science in 1993 and started work at a public library. He quickly moved to corporate libraries, and the job became increasingly digital. Part of the change was due to the new environment. Another part was the changing means with which we store and access information. These factors play into our ability to forget. They pale, however, on comparison to insistence on maximum efficiency. As the oughts became the teens, by father was subjected to an increasing standard of professional responsiveness. The data existed, therefore he could find the information, and find it quick thanks to technological innovations.

Research, however, is not affected by the amount of available information. A researcher still has to do the work of finding and compiling the right details.

The burden placed on my father and his fellow corporate librarians to get business research done right and faster than ever guaranteed that their work would be undervalued. His eventual redundancy resulted from the expectation of instant gratification that computerized research provides. Partners and associates didn’t feel the need to consult a researcher when they could pull results that seemingly provided a complete description from a Google search, or a corporate dataset.

Hence partners and associates forgetting the importance of business research in the large firm. The pressures in a corporate economy often get the better of business researchers’ end-users. Other things might move quickly, but the fact of the matter is that quality research takes time, and that doesn’t just mean working overtime to produce some result.

Human research captures the nuance of each problem, and such nuance is critical when working with customers or colleagues. It marks the difference between showing that one cares for the others’ interests and an attitude that reduces a person’s interests to a problem that needs solving.

The corollary to this observation is that research is creative. Drawing different strands of networked information together generates new ideas. The methods used build value, because they refine the way in which knowledge is stored and how it can be retrieved. The end result creates and inspires new thoughts. It passes information through the funnel that is a researcher’s mind. Each instance, procedural or substantive, breeds novelty.

The value in this human phenomenon is oftentimes displaced by immediate concerns. The sausage gets made without regard for the consequences.

One of those consequences is the loss of respect for the researcher or the knowledge manager. They are erudite gatekeepers removed from practise, punctilious: abstract. Indeed they can be so many words. They are also diligent workers and able institutional resources. These qualities shine through in the long term. People often only see the bottom line.

The tools that changed my dad’s job also give it new meaning.

Librarians and researchers now contend with a virtually infinite knowledge base. Pinning the issues down is more complex, with greater diversity of opinion, because those opinions are readily accessible in a click. They no longer curate physical collections.

This changed job description nevertheless maintains its roots: librarians and researchers must still dedicate their working lives to understanding others’ needs, translating those needs into research questions, and building answers. Those answers are needed without delay and are subject to information that changes instantly with electronic publication. The job isn’t for everyone, yet employing a researcher is beyond most people’s means.

Hence the appearance of freelance or subscription researchers, whose role is to serve as trusted advisor and knowledge base. This role can help small businesses by enhancing their market intelligence at affordable rates; it can also build strategic insights, thus allowing businesses to change tack on a dime. For lawyers in particular, third-party researchers check biases and question arguments. These functions ultimately make for stronger businesses and better representation.

The short form? Consider building a relationship with a researcher.

This post is cross-posted to canlii.

Some notes on contempt of court are in order after the Chief Justice of Manitoba’s Court of Queen’s Bench, Glen Joyal, heard in open court that the private investigator following him to his home was employed by one of the barristers pleading before him. Justice Joyal noted that such tactics could constitute obstruction of justice. They may also be a contempt of court by scandalizing the court.

The scandal in this occurs because the President of the Justice Center for Constitutional Freedoms, John Carpay, authorized the surreptitious surveillance of the Chief Justice. Mr. Carpay was in fact surveilling a host of senior government officials to determine whether any of them were violating COVID-19 health guidelines. This surveillance program was carried out while Mr. Carpay and Mr. Jay Cameron, the Centre’s litigation director, represent seven churches’ constitutional challenges to Manitoba’s COVID-19 health regulations before Justice Joyal.

Mr. Carpay has denied that the surveillance has anything to do with his organization’s involvement in the court case.

This note gives practitioners (and interested members of the public) a sense of the law surrounding criminal contempt of court. It describes some of the cases and then applies the cases to the facts described by Chief Justice Joyal.

The law of criminal contempt of court

The Supreme Court of Canada recognized contempt by scandalizing the court in Re Duncan. In that case, a barrister leveled an accusation of partiality against Justice Locke for which he had no proof and no basis for levelling. The Court took umbridge and, of its own motion, compelled the barrister to answer a charge of contempt. The barrister utterly failed, with the Court fining him $2,000 lest he be imprisoned for 60 days. He was also required to personally apologize ‘unreservedly in open Court for the statements made by him’. Until the apology was made, the Court prohibited him from appearing before the Court at the bar or in chambers. The Chief Justice described contempt by scandalizing the court as ‘any act done calculated to bring a Court into contempt or to lower its authority’ (p. 44).

Taking a broader (and more modern) view of the concept, contempt by scandalizing the court is a common law criminal offense, one of the only such offenses in Canada. The offense was described in R v Prefontaine with reference to its constituent elements:

in my view the actus reus of the offence, which must be established beyond a reasonable doubt, is whether a reasonable person in the community, well informed of the circumstances of the case, would conclude that by reason of the statements made, there was a serious risk that the administration of justice would be interfered with and that this risk is serious, real or substantial. In that context, I include the adjudicative process that is the “business of the court.” (para. 75)

…

McEachern C.J.A., in MacMillan Bloedel Ltd. v. Brown (1994), 1994 CanLII 3254 (BC CA), 88 C.C.C. (3d) 148 also adverted to recklessness being an element of criminal contempt when distinguishing criminal from civil contempt (at paras.91 and 92):

The act which constitutes civil contempt of court is the act of disobeying a court order. The mental element of civil contempt is that the disobedience must have been deliberate or reckless, that is, the possibility that the act would be disobedient must have been foreseen and ignored.

Criminal contempt contains all the elements of civil contempt. In addition, the act of disobedience must have been undertaken in a public way; and the deliberate or reckless act of disobedience must have been undertaken with an intention that such a public act of disobedience would tend to depreciate the authority of the courts, or, alternatively, with foresight that it might do so and indifference to whether it did so or not. (Emphasis original, para. 91)

These elements of the offense apply with reference to statements made in or about the courts. The statement must present a grave risk to the administration of justice and the accused’s state of mind must demonstrate, at a minimum, that the accused did not care whether the courts’ authority would be lessened by his gesture.

Prefontaine makes for difficult precedent because its facts deal with statements made before the courts. Such offenses are much more readily tried than statements made outside the court, let alone acts done outside the court.

Criminal contempt is reserved for the most flagrant cases that disrespect judicial authority. This observation is especially true when the only matter at issue are comments about the court or its judicial process. One of the controlling cases on this point is Regina v Kopyto. The Ontario Court of Appeal there held that a lawyer’s criticism of a court’s decision outside the courtroom was ground for contempt. The lawyer’s freedom of expression, however, restrained the Court’s ability to uphold a finding of contempt. The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms protected a lawyer’s speech from criminal prosecution (although lawyers may still face professional discipline–see Histed v Law Society of Manitoba, para. 68). Justice Cory was, however, quick to add that:

The decision in this case should not be taken as a conclusion that the offence cannot exist. It is in effect a common law offence that, as presently defined, cannot meet the constitutional requirements of the Charter, and not an offence created by statute. The courts created the offence and thus the courts, as well as the legislature, might modify it to meet the requirements of the Charter. For example if the Crown were to prove:

that an act was done or words were spoken with the intent to cause disrepute to its administration of justice or with reckless disregard as to whether disrepute would follow in spite of the reasonable foreseeability that such a result would follow from the act done or words used;

and that the evil consequences flowing from the act or words were extremely serious;

and as well demonstrated the extreme imminence of those evil consequences, so that the apprehended danger to the administration of justice was shown to be real, substantial and immediate;

then the act or words could be punishable as a criminal offence in order to ensure the functioning of the judicial process.

The test summarized by Justice Cory is a concise and compelling statement of the offense. More to the point, Justice Cory’s statement applies across fields of conduct. Statements and actions are captured by the test.

Criminal contempt in 2021

The facts that Chief Justice Joyal described appear to constitute grounds for criminal contempt.

The central element to the offense in this case is that a litigant knowingly continued to surveil the Chief Justice while prosecuting a constitutional challenge before him. The challenge argues that COVID-19 public health orders barring religious congregations from assembling to worship infringe Charter rights to freedom of conscience/religion, expression, and peaceful assembly. While pleading this case, John Carpay, the President of the Justice Centre for Constitutional Freedoms, also had a private investigator surveilling the Chief Justice. The idea was to catch the Chief Justice in the act of violating COVID-19 health restrictions.

Once the Chief Justice pointed up the surveillance, Mr. Carpay was quick to apologize.

Justice Cory’s test comes into view.

Mr. Carpay ordered an act that, though likely not intending to cause disrepute to the Court’s administration of justice, arguably recklessly disregards the possibility of disrepute. In this case, that possibility obtains from either from the litigants desire to embarrass the judge in its case, thus affecting the outcome, or the perception that the judge is biased by the affront.

To be clear, Justice Joyal ought to be taken at his word that no bias will ensue.

The consequences flowing from Mr. Carpay’s decision must be extremely serious, and they are again arguably so serious. This is not a case where a lawyer expressed an intemperate or poorly worded opinion. A barrister breached the barrier between a judge’s public function and his personal life. Being followed from one’s place of work through the streets and to one’s home is inherently threatening.

This factor flows into Justice Cory’s third criteria: the danger to the administration of justice is substantial and immediate–so immediate in fact that the legislator created an offense for this conduct. Section 423.1 of the Criminal Code prohibits provoking ‘a state of fear’ in a judge to ‘impede him or her in the performance of his or her duties’. The state of fear required by section 423.1 does not necessarily need to result. The English Court of Appeal in R v Patrascu ([2004] EWCA Crim 2417 [2004] 4 All ER 1066 at [16]-[18]) observed that intimidation arises when a person intends to induce a state of fear in her or his target. In Canada, intimidation occurs when the ‘natural and probable’ consequences of a person’s actions lead to intimidation (R v Bergeron, paras. 19-22; vide. R v Armstrong).

The existence of a criminal offense for the conduct in this case demonstrates Justice Cory’s requirement for ‘the extreme immanence of those evil consequences’. The legislator has declared intimidation of judicial officials a danger, thus making it real for the purposes of the justice system. Intimidation is itself an offense punishable by up to fourteen years imprisonment–a substantial sentence to deter a substantial threat to the administration of justice. In this case, a judge was followed to his home, which (I am at pains to indicate) is conduct that presents an immediate danger to a reasonable person’s mind.

Conclusion

Justice Cory’s prescriptions are fulfilled, which is suggestive of the gravity of the offense created by Mr. Carpay’s conduct. Justice Joyal pointed up some of the stakes when he said that:

I am deeply concerned that this type of private investigative surveillance conduct could or would be used in any case involving any presiding judge in a high-profile adjudication.

His concern begs the question. Mr. Carpay has expressed genuine contrition, but his conduct may still be condemned and punished. Prosecutors and courts will ultimately have to decide whether such a sanction is worthwhile, and there is some meat on the bones of a common law charge of contempt of court.

Check out a.p.strom’s aviation law practise

This post has been updated after correspondence with Transport Canada regarding its aviation medicine certification regime. 21/06/21.

Transport Canada’s Civil Aviation Medicine (CAM) program has continued a discriminatory policy against subjects who present with mental health conditions that would not pose a danger to aviation safety. CAM has done so by misinterpreting and misapplying its enabling legislation. These faults amount to a breach of subjects’ right to equality; they also show that Transport Canada has not minimally impaired subjects’ rights or balanced the purported benefits of its discriminatory policy with the ill effects that subjects with mental health conditions suffer.

This note reviews the CAM program’s legislated standards and policy documents and considers them against the Australian example while applying Canadian human rights norms to show how the discrimination occurs.

Scitote

Aviation safety is, to be abundantly clear, a very legitimate purpose. That legitimacy, however, does not give doctors the ability to impose discriminatory and restrictive standards without an evidence-based rationale that substantially complies with aviation law and with Canadian human rights obligations.

Introduction

The current regime at Canadian Aviation Medicine has, as I have previously indicated, impinged upon subjects’ human rights when they disclose a history of mental health concerns during the medical certification process. After further reflexion, the problem appears to run deeper than previously indicated.

The short version is that Canadian Aviation Medicine aims to certify pilots as safe to fly. Their regulatory documents all indicate that any condition that renders a pilot unable to safely exercise the privileges of her or his license will be denied medical clearance. Canadian Aviation Medical Examiners (‘CAME’) and Regional Aviation Medical Officers (‘RAMO’) are bound to apply Transport Canada policy; that policy currently openly discriminates against mental health concerns by assuming that all mental health conditions render a person unfit to fly based on the prevailing standards.

As stated earlier, the Canadian Aviation Regulations Part IV, Standard 424.17 (4) specifies the physical and mental standards for medical categories. The standard related to mental issues is stated in 1.3 (a), 2.3(a), 3.3(a), 4.3(b):

“The applicant shall have no established medical history or clinical diagnosis which, according to accredited medical conclusion, would render the applicant unable to exercise safely the privileges of the permit, licence or rating applied for or held, as follows: (a) psychosis or established neurosis.”

At first glance this would render anyone with any history of depression, anxiety or other neurosis unfit to be licensed to fly. However, Transport Canada Civil Aviation Medicine has developed an approach to this issue that considers individual circumstances more intently.

Additionally, the use of medications for treatment of these disorders raises regulatory questions as stated in 1.1(d), 2.1(d), 3.1(d), 4.1(d):

“The applicant shall be free from (d) any effect or side effect of any prescribed or non-prescribed therapeutic medication taken, such as would entail a degree of functional incapacity which accredited medical conclusion indicates would interfere with the safe operation of an aircraft during the period of validity of the licence.”

Again, recognizing that the use of medications to treat mental issues is generally a positive step, but does complicate the considerations for medical certification TC CAM has established an approach that individualizes the decision making process.

Handbook for Civil Aviation Medical Examiners – TP 13312, emphasis added.

The discriminatory assumption is subtle, but present: the medical standard requires all medical evaluations to focus on whether the individual can safely operate an aircraft and exercise all of the privileges (and responsibilities) imposed on holders of aviation licenses. This requirement is immediately interpreted by Civil Aviation Medicine as ‘render[ing] anyone with any history of depression, anxiety or other neurosis unfit’. CAM is quick to downplay this statement by advertising its new policy, but its handbook elsewhere indicates that particular ‘psychiatric diseases’ presumptively render a person unfit. The subtle bias signaled by that ‘first glance’ remains, and CAM’s response to a presumptive determination is to immediately begin considering whether the person assumed to be unfit qualifies for an exemption pursuant to sub-section 404.05(1) of the Canadian Aviation Regulations:

(1) The Minister may, in accordance with the personnel licensing standards, issue a medical certificate to an applicant who does not meet the requirements referred to in subsection 404.04(1) where it is in the public interest and is not likely to affect aviation safety.

This exemption relies on a proper determination that an applicant is unable to safely pilot an aircraft or serve as an air traffic controller. Civil aviation medicine’s approach improperly determines this point because it operates on the assumption that all mental health conditions render a person unfit without any additional investigation.

This note shows how Canada’s Civil Aviation Medicine program is constitutionally deficient. Specific reference will be made to sections 15 and 24 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which allows a court to review Transport Canada’s conduct. These sections read:

15 (1) Every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination and, in particular, without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.

24 (1) Anyone whose rights or freedoms, as guaranteed by this Charter, have been infringed or denied may apply to a court of competent jurisdiction to obtain such remedy as the court considers appropriate and just in the circumstances.

Constitution Act, 1982, enacted as Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982, 1982, c. 11 (U.K.)

These provisions come into play as a result of the government’s actions; its legislation (which would be controlled by section 52 of the Charter) is free from bias. This note concludes by calling for a new approach to aviation medical certification that treats subjects with the dignity that section 15 is meant to protect while ensuring aviation safety for all.

Canadian aviation medicine, discrimination, and its effects

Canadian aviation medicine operates under the Aeronautics Act, which is federal legislation that incorporates standards from the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) into Canadian law. Its program is discriminatory not because the law makes it so; the doctors running the program instead make a host of assumptions about mental health that undermines the letter of the law (which may be a crime). The systematic effect of this discrimination perpetrates a violence on subjects that Hannah Arendt describes with brutal prescience:

In a fully developed bureaucracy there is nobody left with whom one can argue, to whom one can present grievances, on whom the pressures of power can be exerted. Bureaucracy is the form of government in which everybody is deprived of political freedom, of the power to act; for the rule by Nobody is not no-rule, and where all are equally powerless we have a tyranny without a tyrant.

On Violence (London: Allen Lane, 1970), p. 81

That initial assumption made within Transport Canada’s bureaucracy creates a hurdle over which subjects have significant problems jumping. The discrimination visited upon these subjects is thus twofold: it creates an immediate denial of the privilege to which they may be legally entitled; it also imposes a much more difficult set of bureaucratic processes to disprove the immediate denial.

This discrimination is typically justified with reference to aviation safety. This justification fails in the measure that its proponents cannot identify specific concerns that would preclude those with any mental health condition from flying. Chronic depression, for example, is treatable and, in some cases, results in no impairment that could affect aviation safety. So, too, is high anxiety. Ignorance is an unfortunate justification. It underscores the need for subjects to navigate the Transport Canada bureaucracy to receive equal treatment.

A common, more informed refrain used to justify Canadian aviation medicine’s biases is that ICAO imposes these standards. The Chicago Convention creates a worldwide set of standards for aviation, which includes medical standards for pilot and air traffic controller (ATC) certification. This shibboleth is quickly disproven by looking to the international context in which Canada’s medical standards exist.

Effect of discrimination

Prior to considering these standards, the effects of Canada’s discriminatory system ought to be fleshed out.

The initial assumption

A medical examination system that begins with an instruction to discriminate is, at first glance, a deeply biased system. The onus (as I have elsewhere shown) rests on individual applicants not only to convince doctors to shake their biases, but also to convince the Government of Canada to change its policy. This is a heavy charge for which most individuals are ill-equipped and under-resourced.

Bias against mental health conditions creates a violation of the Canadian Charter because section 15 requires Transport Canada to apply the law equally to those people who disclose mental health disabilities. The Supreme Court thus said that: ‘The essence of stereotyping … lies in making distinctions against an individual on the basis of personal characteristics attributed to that person not on the basis of his or her true situation, but on the basis of association with a group’ (Winko, para. 87). Canadian Civil Aviation Medicine includes this stereotype in its Handbook for Civil Aviation Medical Examiners. All mental health conditions are presumed to be disqualifying without reference to individual cases.

Transport Canada only takes a case-by-case approach to grant exemptions from the strict medical standards. The burden and cost of obtaining these exemptions falls on individual applicants, pilots, or air traffic controllers.

The Canadian Aviation Regulations, however, which incorporate Standard 424 relating to medical certification, require an individualized process that specifically exempts stereotyping:

The applicant shall have no established medical history or clinical diagnosis which, according to accredited medical conclusion, would render the applicant unable to exercise safely the privileges of the permit, licence or rating applied for or held, as follows:

(a) psychosis or established neurosis;

Physical and Mental Requirement, amended 2007/12/30, emphasis added.

(b) alcohol or chemical dependence or abuse;

(c) a personality or behaviour disorder that has resulted in the commission of an overt act;

(d) other significant mental abnormality.

The required examination must assess whether any of the listed conditions would, in the applicant’s individual circumstances, create a safety hazard.

Standard 424 also indicates that a CAME must grant the highest medical certification possible based on the evidence before them: ‘An applicant shall be granted the highest assessment possible on the basis of the finding recorded during the medical examination.’

Based on these provisions, that Standard is not only constitutionally acceptable. It is an exemplar of the individualized process required by Canadian constitutional law.

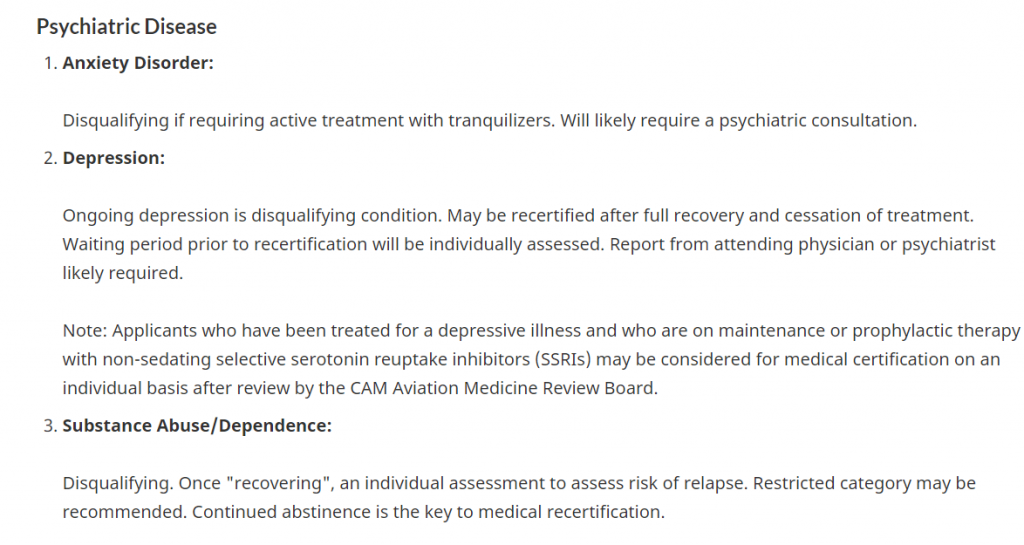

The implementation of this policy, however, leaves much to be desired. The Handbook for Civil Aviation Medical Examiners contains these standards:

The presumption could not be clearer: all anxiety- or depression-related conditions are disqualifying. Pilots are not fit to fly if these conditions are present. The individualized consideration given to applicants appears to fall under section 404.05 of the CARs, which is invoked only when a person is found to be unfit. This added burden creates a disadvantage for applicants with mental health conditions. Transport Canada resists this interpretation, but the use of the words ‘may be considered for medical certification’ after a paragraph that declares depression a disqualifying condition indicates that the disqualification has occurred.

These instructions violate Standard 424 because they do not engage in the required assessment for fitness to fly before implementing the Minister of Transport’s ability to license with conditions.

Pilots and ATC presenting with mental health conditions thus do not benefit from an even application of Standard 424. This discriminatory treatment disadvantages pilots with minor mental health conditions, like dysthymia or some anxiety disorders. These conditions may persist throughout a person’s life and not interfere with her or his aviation duties. They may also be treated with maintenance therapies.

These options are only acknowledged as grounds for exempting a person from medical standards, which means that a professional pilot or ATC may face an indefinite license suspension if she or he discloses a mental health condition. An indefinite suspension is, for most pilots, detrimental to their careers, yet Civil Aviation Medicine does not seem responsive to these grave risks.

Private pilots investing time and money in their hobby are, of course, less affected by these strictures. Their interest is typically more personal. A discriminatory decision from Civil Aviation Medicine will only affect property interests in aircraft or the like.

Either way, though, discrimination hits hard. Research shows that the stigma of perceived discrimination can negatively impact a person’s mental health. An applicant’s pre-existing condition may thus be worsened by Civil Aviation Medicine’s behaviour, which result stands at odds with CAM’s mission and doctors’ ethics.

The violence of bureaucracy

Discrimination is bad enough. Systematic discrimination, for most, is insurmountable due to the sheer size of government bureaucracy. Once this part of the story gets added to the mix, the violence visited upon individuals who disclose that they have a mental health condition becomes acute. The government stands as a representation for wider social stigma, which can be perceived as reflecting Canadian society and/or as reflecting the Canadian aviation community. Either way, stigma that is reinforced by government magnifies the deleterious effects of discrimination on applicants’ mental health.

The wider issue, in bureaucratic terms, is that pre-existing institutional bias that must be reversed by individual applicants creates an institutional culture that prides itself on maintaining bias. Doctors are far from immune to this impulse, specifically as it concerns mental health.

Canadian Civil Aviation Medicine is demonstrative of these ills. The authority accompanies its discriminatory language with discriminatory requirements. CAM automatically imposes a reporting requirement on individuals with mental health conditions. If a person is licensed, they are required to submit medical information about their conditions. Private pilots must submit a report every three months. Professional pilots and air traffic controllers must submit every six. This requirement infantilizes licensees with mental health conditions by assuming that all mental health conditions render a person incapable of judging when she or he is fit to fly. It also duplicates reporting requirements, because treating physicians are required to report any ‘medical or optometric condition that is likely to constitute a hazard to aviation safety’ (Aeronautics Act, s. 6.5). If a licensee decides to stop treatment, for example, a physician would have to report that decision to Transport Canada.

Courts have already recognized that Transport Canada discriminates against individuals presenting with mental health conditions. In Canada v Bethune, the government sought judicial review of a Transportation Appeal Tribunal decision that ordered Transport Canada to reconsider a decision to deny Mr. Bethune medical certification. Mr. Bethune applied for a Category 2 medical certification to become an air traffic controller after passing NAV Canada’s rigorous tests. He had the job, and was forthright in disclosing persistent sadness to the CAME. After several months of waiting, he was forced to decline NAV Canada’s offer because Transport Canada had not yet decided on his medical certification. When it finally ruled against him, he appealed on the grounds that Transport Canada had applied the incorrect policy document: a newer policy was in force. The Tribunal ruled in his favour and held that: ‘The criterion at issue was whether Mr. Bethune had a “significant mental abnormality” that would render him unable to safely exercise the licence at issue – an air traffic controller licence’ (para. 9). The government, worried about precedent, sought judicial review in Federal Court. Justice Phelan agreed with the Tribunal and admonished government counsel in these terms:

It was suggested in argument that no new information would change the Minister’s decision. I take this as a piece of enthusiastic argument and not as a statement of Ministerial policy. If it were policy, there could be grave consequences to a biased and bad faith reconsideration.

Para. 17.

Bethune was decided in 2016; Standard 424 was never at issue in that case. Its application was at issue. The Transportation Appeal Tribunal and the Federal Court each held the government to an individualized process and evidence-based standard that complied with the words in Standard 424. That Standard, to be clear, has not been amended since 2007.

Mr. Bethune’s case unfortunately did not end in cheers. Transport Canada obeyed the letter of the court’s order. It reconsidered the decision. After a year spent waiting, Mr. Bethune was informed that he still did not meet the required medical criteria. Mr. Bethune, frustrated by this dilatory process–one that would wear anyone down–has since happily settled into a fresh line of work.

Ministerial policy has not much changed since Justice Phelan’s admonishment, which brings those ‘grave consequences’ into view. The above-quoted Handbook for Civil Aviation Medical Examiners has not been modified since 2010, when the current discriminatory policy was added as an amelioration to the above-pictured absolute prohibition. Transport Canada’s treatment of Mr. Bethune, moreover, suggests that the Justice Department’s lawyer uttered a premonition in court. Though the judge rightly admonished the Crown, judicial power cannot reform the institutional resistance that ultimately ruined Mr. Bethune’s hopes of becoming an air traffic controller.

Indeed, Transport Canada should be lauded for even considering the prospect that people with mental health conditions take to the skies. Thirty years ago, this was an unthinkable proposition, largely due to ignorance. Now, however, Transport Canada has much more scholarly research about mental health at its disposal. It can craft targeted policies that respond to Canada’s human rights commitments and its concern with aviation safety.

The apathy with which Civil Aviation Medicine has treated this issue runs counter to an evidence-based approach. Justice Phelan commanded such an approach in a specific case, but his writ unfortunately did not extend further.

The resulting lack of close judicial scrutiny means that medical opinion, with its biases, has been allowed to run unchecked through Canadian Civil Aviation Medicine. To be clear, the present cohort of Regional Aviation Medical Officers listed in CAM’s directory are all family physicians whose professional certifications disclose no training or expertise in mental health. This lack of intermediate-level experience may allow biases to run unchecked, for expertise called in at such a remove from individual applicants is at the mercy of pre-established first- and second-line medical opinion.

These opinions in the current regulatory environment identify applicants based on stigma, not individualized analyses. No one person is to blame, but Transport Canada is responsible for a bureaucracy that defines people by a cross-section of traits. These traits then become a person’s institutional identity at Transport Canada. Doctors wind up defining applicants without regard for their dignity or actual aptitudes.

A note about aviation safety

This commentary has so far focused heavily on Transport Canada’s faults. A disbelieving reader might grasp for an easy argument: people with unstable mental health are inherently unpredictable, and medication does not cure such ills. This argument is dated and borne of ignorance regarding the state of research in mental health.

The proper balance between safety and the right to be treated equally for those who have a mental health condition already exists in the Canadian Aviation Regulations. Any health condition must be shown to impair the safe exercise of the privileges of a person’s license. This burden falls upon the doctors employed by Transport Canada.

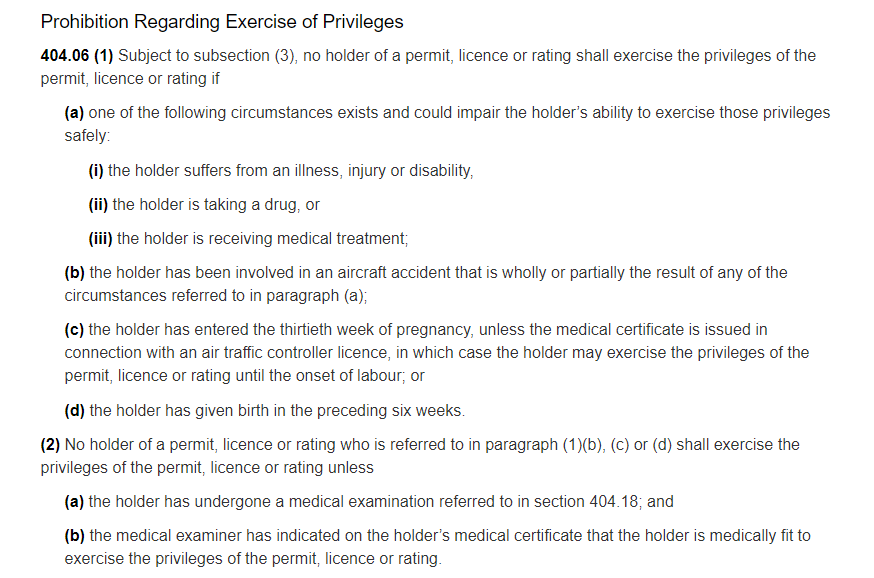

What’s more, once a person is licensed, they are obliged to self-assess prior to each exercise of the privileges associated with her or his license. Section 404.06 of the Canadian Aviation Regulations is crystal clear:

These provisions show that the legislator considered health conditions that could arise during the course of a person’s license. Instead of placing the responsibility upon the Minister of Transport to verify that every pilot is always compliant (an impossible task), the legislator instead made pilots responsible for their conduct.

Civil Aviation Medicine does not address this part of the Civil Aviation Regulations in its policy documents.

The implication, however, of this section is quite broad with respect to mental health. The current policy just discriminates; a more constructive approach in line with aviation safety is to consider mental health in conjunction with the ability to cognize and apply section 404.06. The question then becomes: if a pilot’s depression is such that they cannot safely pilot an aircraft on a particular day, is the pilot able to restrain herself or himself from exercising the privileges of her or his license?

Civil Aviation Medicine would no doubt reply that a pilot in this position could be impaired because some mental illness and associated treatments reduce reaction times. These kinds of problems, however, are legitimate concerns that warrant restrictions on a license or a refusal to license in particular cases, where evidence shows that individuals present safety hazards. The instant problem addresses a catch-all, or blanket approach to mental health that (to its credit) indiscriminately discriminates.

Canadian aviation medicine on the international stage

Other aviation communities have shown far greater leadership when it comes to medical licensing and mental health. Australia’s medical certification regime is a paragon that incorporate open treatment of mental health.

The strengths of Australia’s regime lies in the clarity with which medical standards are promulgated and communicated to doctors and the public. Clarity and a forthright approach to mental health reduce stigma.

Australian civil aviation medicine

Australia’s open approach to mental health conditions relies on regulations that are virtually identical to Canada’s. The difference lies in the country’s approach.

The Civil Aviation Safety Authority’s information page, for example, indicates that each case is unique and there are no textual markers of discrimination. The relevant section of the Designated Aviation Medical Examiners’ clinical practise guidelines indicates that ‘well managed depression is compatible with certification’. The guidelines take a neutral tone; they inform medical specialists about the procedures to be applied in cases that disclose mental health conditions. They also establish patient expectations regarding their condition and the steps needed for certification.

The absence of any mention of mental illness as a disabling condition, although implied, contrasts with Canada’s Handbook for civil aviation medical examiners, which expressly states that mental health conditions are disqualifying. Only after this statement operates on each applicant does Civil Aviation Medicine turn to creating exceptions based on an individual’s condition.

The Civil Aviation Safety Authority (CASA) goes so far as to provide the public and DAME with case scenarios for further clarity.

One such scenario coupled with CASA’s information page is suggestive of Australia’s positive approach. The subject of this scenario is a mid-life initial applicant for a medical certification. The certification is required to obtain a private pilot’s license. The subject discloses a history of depression that has responded well to medication. The subject is alert to his condition and can understand when he is unable to fly. The DAME reviewed the subject’s file, concluded that his condition was not serious enough to warrant rejecting his application. CASA (in this example) issued a certification with the proviso that the subject submit an annual report from his doctor regarding his depression. He was also restricted from flying if his condition or treatment changed pending a DAME review.

This scenario gives applicants and DAMEs a case-based framework with which to understand CASA’s evaluation protocol.

Australia’s Civil Aviation Safety Regulations are, moreover, quite a bit clearer than Canada’s when it comes to medical certification and mental health. Regardless of the class of license, a person is considered fit to fly if they do not have an

established medical history or clinical diagnosis of any of the following conditions, to an extent that is safety?relevant:

(a) psychosis;

(b) significant personality disorder;

(c) significant mental abnormality or neurosis

Tables 67.150, 67. 155, 67.160.

These criteria are a far cry from Canada’s more restrictive criteria in Standard 424, which gestures toward mental health concerns without indicating the severity required to trigger aviation medical certification concerns. Australia’s standard is clear: the mental health condition must rise to a level that significantly impairs a person’s psyche.

This standard coupled with public-facing documents that provide sufficient detail regarding acceptable mental health conditions and outcomes help de-stigmatize mental health in aviation medicine. They have, moreover, not created any significant additional safety concerns.

Rights, minimal impairment, and a proportional rule

Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees equality to all before and under the law. The government may breach this guarantee to ensure social cohesion and public safety (s. 1). Any breaches in this regard must be prescribed by law. Where the law authorizes a breach, that breach must minimally impair subjects’ rights and/or must be proportionate to its policy objectives (R v Oakes). Breaches will often need to be justified with reference to social science evidence (Mounted Police Association of Canada, paras. 143-4).

Canadian aviation medicine’s offending conduct derives from law, but is not itself law. It is a policy of government that dictates Civil Aviation Medicine’s approach to mental health issues. This policy may be defensible as law if it is ‘authorized by statute’ (Greater Vancouver Transportation Authority, para. 65). The above analysis, however, shows that CAM has created a policy that offends its enabling legislation, the Canadian Aviation Regulations. As such, CAM’s policy is not authorized by statute, so its discriminatory conduct cannot be protected by the Charter.

Even if its conduct were protected by the Charter, CAM’s policy does not balance subjects’ right to equality with a very legitimate interest in aviation safety.

The need for balance is prescribed by the venerable Oakes test:

- The objective of the law must be pressing and substantial (aviation safety is pressing and substantial);

- A rational connection must exist between the law and the objective (one does exist in this case);

- The law must be minimally impairing (the law in this case is minimally impairing; CAM’s policy is not);

- The law’s effect on subjects must be proportional to the social benefit derived from the infringement of subjects’ rights (the law in this case is proportional; CAM’s policy is not).

These latter categories create difficulty for Civil Aviation Medicine because any justification of doctors’ conduct requires an admission of disregard for the affected population or a plea of ignorance that arises from a lack of adequate aeromedical specialization in mental health issues.

Minimal impairment is not a difficult standard; it’s the standard of a decent, rational professional. This professional’s knowledge extends to the context in which they work and in which their field is situate. Civil Aviation Medicine, for example, is populated by doctors, whose medical knowledge also allows them to understand the limits of their expertise. These doctors are literate, and have knowledge of the regulatory context in which they work. They are also able to conduct further research on matters related to their duties, whether those be evaluating applicants for medical certification or crafting policy. Keeping to their creed, doctors also advocate for patients to the best of their ability.

This synopsis derives from Canadian jurisprudence regarding minimal impairment. The courts require government to show that it has chosen a policy from a range of reasonable alternatives (Health Services, para. 150). Enhancing the administration of a government program is not minimally impairing, even if such enhancement might benefit a greater population (Health Services, para. 151). The government must instead show that it considered its policy alternatives with regard for the interest of the affected population (Health Services, para. 150; Charkaoui, paras. 76, 86). When government action is being challenged, analogies may be drawn between the duty to accommodate under human rights law and Charter violations to show whether the government did its utmost to protect minority interests (Multani, para. 53). Minimal impairment may, moreover, be made out with reference to other jurisdictions (such as Australia) and to other international treaties to which Canada adheres (Carter, paras. 103-4; JTI Macdonald, para. 10; Whatcott, para. 67).

Civil Aviation Medicine’s current policy fails to show regard for applicants’ interest as a group that is potentially disadvantaged by CAM’s current practise. The practise of assuming that an applicant presenting with a mental health condition is immediately unfit to fly is inductive. It applies a group characteristic (in this case, a stigma) to more efficiently process medical certification applications. I am told that CAM processes over 50,000 of these a year: the current staff have to keep up. The implication of this statement is clear. Applications may be moved along faster than needed to ensure that the system runs smoothly; the courts do not tolerate this excuse. Analogies between the duty to accommodate and CAM’s practices also point to the problem. CAM does not accommodate in the initial phase of an application, where a person’s safety record is not yet in evidence. Accommodation only occurs after Transport Canada has stigmatized the applicant, and this is no accommodation at all if the applicant could have been assessed as medically fit.

Canada’s international obligations overwhelmingly support a more enlightened approach to mental health in aviation. The United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights guarantees a right to equality (article 1) and freedom from discrimination (article 7), subject only to ‘such limitations as are determined by law’ (article 29). The United Nations’ High Commissioner for Human Rights reported in 2017 that: ‘the experience of living with mental health conditions is shaped, to a great extent, by the historical and continuing marginalization of mental health in public policy’ (para. 14). The Commissioner went on to say that:

This stereotyping, prejudice and stigmatization is present in every sphere of life, including social, educational, work and health-care settings, and profoundly affects the regard in which the individual is held, as well as their own self-esteem. The lack of systematic training and awareness-raising for mental health personnel on human rights as they apply to mental health allows stigma to continue in health settings, which compromises care.

…

The full participation of affected communities in the development, implementation and monitoring of policy has a positive impact on health outcomes and on the realization of their human rights. Ensuring their participation supports the development of responses that are relevant to the context and ensures that policies are effective. Participation in lawmaking and policy design in mental health has typically been directed at health professionals, as a result of which the concerns and views of users, persons with mental health conditions and persons with psychosocial disabilities have not been systematically taken into account and harmful practices have been perpetuated and institutionalized in law and policies.

Paras. 16, 43.

ICAO, an organization based in Montreal, is closely affiliated with the United Nations. Its membership requires that a state also possess membership in the United Nations (Chicago Convention, art. 93 bis). UN members are subject to human rights obligations stemming from the UN; ICAO’s membership is subjected to those obligations. Medical standards promulgated under the Chicago Convention must therefore accord with international human rights obligations.

The last phase of the Oakes test balances the effect of a practise on individuals with its positive outcome for the general population (Frank, para. 76; KRJ, paras. 77-8).

The effects of CAM’s practise have been noted above. Their rehearsal here is only to note that the treatment of mental health conditions afforded to prospective and actual pilots and air traffic controllers can have life-altering consequences. Discrimination and perceived discrimination violate a person’s dignity and can impact her or his self-esteem. More critically still, CAM’s treatment may worsen a person’s mental health. Professional pilots and air traffic controllers may lose their livelihoods, which is a stressor that impacts mental health. It only takes a few words to capture these consequences, but for those affected by mental health conditions, the ramifications are much broader. The stigma still associated with mental health is, as noted above, enhanced when it is directed by the impersonal face of government. Individual well-being is seriously undermined.

The social benefit derived from such discrimination is minimal at best. Aviation safety is adequately protected when Civil Aviation Medicine turns its attention to the individual applicant in order to assess her or his actual ability. Treating physicians are, moreover, required to report any potential risks to aviation safety. The mechanisms maintain the balance between aviation safety and individual rights. A blanket prohibition that requires applicants to prove their fitness for an exception to that prohibition only serves to make Civil Aviation Medicine’s case processing more efficient. It does not address the legitimate aviation safety concerns that benefit society.

The effect of CAM’s policy is, then, far more dire than further adjustments to its policy.

Check out a.p.strom’s aviation law practise

This piece is released as part of a broader book project currently soliciting funds via Kickstarter.

Aequitas sequitur legem: equity follows the law, which concept expresses the victory of common law over its equitable counterpart. There is good reason for this win, for the ancient law of equity was administered by the Lord Chancellor, a royal officer whose court in chancery also served as a clearinghouse for royal records. Modern rhetoric about the rule of law absolutely avoids this kind of confusion; Montesquieu’s doctrine about the separation of powers prevails. This classificatory system, like common law, emphasizes the impersonal, monolithic qualities of industrial government. Adam Smith, for example, lauded impersonal justice as the great strength of England’s legal system: ‘When the judicial is united to the executive power, it is scarce possible that justice should not frequently be sacrificed to what is vulgarly called politics’. Smith’s observation is, indeed, the case, yet the independence touted by English jurists is itself a political stance against personal government and the irregularities of personal conscience.

Personal conscience, however, may humanize justice systems when such systems openly account for judges’ consciences in the face of strict legal rules. The ancient discourse surrounding equity founds this theory; its application in common law may derive from the equally ancient rhetoric surrounding the honour of the Crown. Much more theorization in this vein is, of course, needed before judges’ conscience is valued in legal discourse and education. The present work introduces equity and the honour of the Crown. It then details necessary scholarly and practical innovations to renew interest in legal conscience.

Of Equity

The system of law administered by Chancery courts in England and its colonies vied against common law courts for power and judges’ fees. Its roots, however, lie in the religious disposition of successive chancellors: Thomas More (d. 1535) was the first Lord Chancellor of England who was not also a bishop. The King’s chief recordkeeper was a cleric, which over time entitled him to dispense justice in the name of conscience rather than law. This different emphasis gave at first onto a supplementary branch of private law. Common law enforced damages; the Chancellor required subjects to comply with their obligations. These were complementary systems that have since been amalgamated, but not before common law proved ascendant over equity. The short history offered here contextualizes this historic change while underscoring the creative potential that gave equity its start.

The Chancellor’s legal duties were an expression of executive government that evolved into a separate branch of judicature. Fleta, the thirteenth-century commentaries on the law of England, describes the Chancellor’s power to hear and examine subjects’ supplications and quarrels with a view to doing justice by the King’s writs (Bk. 2:13). This formula refers to the Chancellor’s role as clerk to the Crown and the Crown’s representative justiciar. The Chancellor’s conscience over time developed into a set of remedies that corrected the law by virtue of the King’s grace. Joseph Story’s tome on equity thus dates this legal field between the reigns of Henry V (r. 1413-22) and Henry VIII (r. 1509-47). A wide range, but one understandable in terms of centralizing royal power. Henry VIII’s power, for example, allowed him to break from Rome and entrain Parliament in his scheme. His Chancellors, Cardinal Wolsey, Thomas More, the Lord Audley, and Thomas Wriothesley, were some of the first lawmen to occupy the office. Wolsey was the last cleric to enjoy the title.

The battle between common law and equity turns on this new approach to staffing the Chancellor’s office. The incoming Stuart reigns oversaw a growing administrative apparatus that required increased taxes on the population; personal justice via the Chancellor dispensed the Crown’s grace where no legal rule existed. Special cases were reserved to the Crown. The Chancellor did justice against common law according to his conscience. Matthew, chapter 5, summarizes the Chancellor’s mission:

17 Think not that I am come to destroy the law, or the prophets: I am not come to destroy, but to fulfil.

Authorized Version

The King’s grace supplements his law. Such grace cannot, however, stand in the Renaissance as religious belief becomes increasingly fractious. Edward Coke, in the Case of Prohibitions ([1610] 12 Co Rep 63), says that ‘the law was the golden met-wand and measure to try the causes of the subjects; and which protected His Majesty in safety and peace’ (p. 65). This report out of King’s Bench belies the notion of personal grace or dispensation from law. Grace falls further out of favour when the Glorious Revolution (1688) brings the Whig idea of the rule of law into political rhetoric. Law must be predictable and subjugate all, including Lords and Crown.